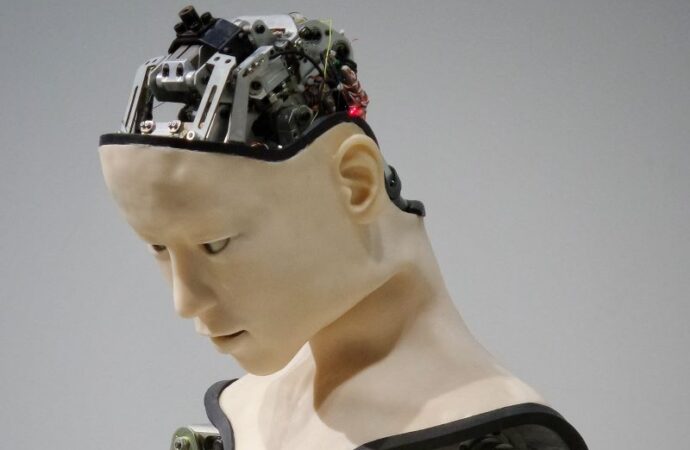

The separation between biological human life and clever AI replicas has been the subject of dozens of science-fiction movies and shows. Star Trek: The Next Generation frequently depicted the endearing Commander Data, a sentient android, entangling himself in awkward situations through his attempts to seem more like his human comrades. Blade Runner 2049 dealt with similar topics, interrogating the subject further by introducing robots that could reproduce and create (seemingly) fertile offspring.

In like fashion, Gareth Edwards’ 2023 science-fiction epic The Creator takes on without hesitation one of modern society’s most pressing issues: artificial intelligence. It deals with AI “simulants,” whose level of sentience and emotional expressiveness blurs the lines between AI and real human beings. In fact, the film’s conclusion is specifically crafted such that the audience does not register a difference between a real person and the consciousness of a real person uploaded into a robotic AI replica of their body.

And while previous films take pains to never definitively answer the myriad of philosophical questions about AI, The Creator has no such subtlety. The protagonist, Joshua (John David Washington), initially believes that simulants are not real people, thinking that any emotion or sentience they may display is “just programming.” Yet this belief is what the movie calls Joshua’s “misbehavior,” a faulty worldview that Joshua must outgrow.

Grow out of the worldview he does, for Joshua becomes a father figure to a simulant in the form of a child named Alphie (Madeleine Yuna Voyles). Plus, in the movie’s final moments, he embraces a simulant replica of his dead wife (Gemma Chan) as if she is the real woman.

The Creator’s declarative endorsement of AI entities as true, sentient life forms sidesteps widespread concerns about the proliferation of artificial intelligence, including issues such as weaponization, copyright infringement, and the replacement of real people by AI in the workforce. After all, if AI “simulants” are real people, then they have the same rights to representation on all these issues as flesh-and-blood humans.

The Creator, then, puts forth a stark, unequivocal position, one with intriguing and ultimately radical consequences. AI becomes more than a question of intelligence. And the questions raised cannot be resolved simply with the Turing Test, which requires that AI bots prove themselves indistinguishable from human thinkers in a text chat.

All these questions do not regard intelligence per se; rather, they deal with personhood, something much more complex. Personhood is not a concept often interrogated by the scientific field of AI: Researchers in this area are more concerned with intelligence (like mathematician Alan Turing) or consciousness (like philosopher Thomas Nagel). This is likely because personhood is not inherently quantitative. Rather, its definition depends heavily on one’s cultural and religious beliefs.

For example, in Japanese culture, there is a common belief that objects, not just living beings, have souls. It is not unheard of for families to have funerals for their robotic AI dogs, mourning the loss as if robots were flesh-and-blood pets. In that case, many Japanese would likely categorize The Creator’s simulants as people with souls—not just lifeless machines that are talented at imitation.

Judeo-Christian thought, however, would almost certainly disagree. The belief that human beings are created in the image of God excludes the belief that a robotic dog or an AI human replica might have a soul and therefore be a “person.” Though this fact is addressed in passing in The Creator, when Alphie remarks that she cannot go to heaven, the film does not explore this thought any further.

It would be easy for a person who believes that souls are only the privilege of humanity to dismiss the idea of AI’s personhood as an example of Hollywood parroting poor philosophy and actively subverting Western thought. Yet this issue is not simply an abstract debate over intellectual minutiae. It is a real social problem in need of a practical solution.

In a society where fundamental concepts of identity and humanity are under radical revision, The Creator’s statement promotes the position that there is no such thing as a soul. Similarly, the film blurs the distinction between a real human being and a machine programmed to be behaviorally but superficially similar to one. This is, of course, the filmmaker’s and studio’s prerogative under free speech. But it should make us wonder: In our world of AI, are we ignoring what it means to be human?

—

Image credit: Unsplash

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *