The values of the French Revolution are those of every radical revolutionary movement that succeeded it, including the one currently dismantling the basic institutions of American society and culture. But there are few historians of the Revolution who can be trusted to avoid propagandizing for it as they write about it. Pierre Gaxotte’s splendidly literate account, long out of print and almost impossible to find in English, expertly covers the stock ground of history—the events from the siege of the Bastille to Bonaparte’s seizure of power—in a political-philosophical framework that puts those events in the proper moral light.

The authority of the Ancien Régime was the result of long centuries of painstaking institution-building. But the ideology of the philosophes and their later, still more radical descendants rejected it based on the flimsiest of rationalist prejudices and misconceptions about human nature.

Even those familiar with the basic facts can learn from Gaxotte’s discussion of the causes of the Revolution. A great lie undergirded by generations of progressivist historians would have it that France was economically and politically crumbling in 1789, and that the Ancien Régime was utterly incapable of commanding the respect of its subjects. But the clearest evidence of popular support for the monarchy and the Church is in the widespread armed resistance that rose up against the Revolution.

The peasants rose up because God and King reached deeply into their lives symbolically and spiritually, providing a kind of sustenance that human beings crave as much as food, and that only those in the grips of a narrow, fanatical utopianism could fail to comprehend. The truth is that France under Louis XVI was a rich country. That wealth extended, albeit unequally, even to most of those at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Such is the precariousness of all human order, even while relatively stable and prosperous; administrative missteps, coupled with the frivolous flirtation of elites with exciting, foolhardy political ideas, can bring it down.

Gaxotte strikes hard at the corrosive effect that American ideas and the American statesmen who embodied and preached them had on pre-revolutionary French society. Our own mythological attachment to some of these founding ideas and individuals notwithstanding, it cannot be denied that the individualist, Protestant fervor of what historian Gregg Frazer aptly named “theistic rationalism” has worked as a solvent to dissolve much of the social glue holding Western civilization together over the centuries. American conservatives who want to get down to brass tacks will have to reckon with what Gaxotte reveals.

—

Dear Readers,

Big Tech is suppressing our reach, refusing to let us advertise and squelching our ability to serve up a steady diet of truth and ideas. Help us fight back by becoming a member for just $5 a month and then join the discussion on Parler @CharlemagneInstitute and Gab @CharlemagneInstitute!

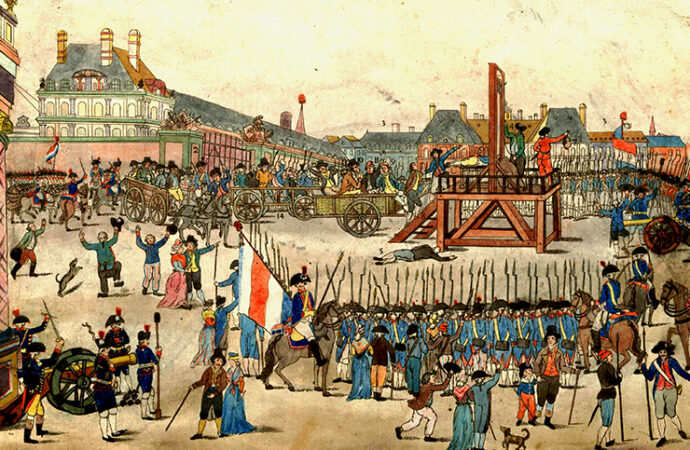

Image Credit:

Wikimedia Commons-National Library of France, public domain

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *