The 1960s, according to Carl Oglesby, a former president of Students for a Democratic Society, “will never level out.”

“It’s a corkscrew, it’s a tailspin, it’s a joyride on a roller coaster, it’s a never-ending mystery,” he continues. “Who won? Who lost? What were the terms of victory and defeat? We’ll always be discussing that.”

I recently edited a book of interviews with leading scholars that investigated the consequences of that decade. As a scholar, I avoided taking a partisan stance on the legacy of the ‘60s for contemporary America. But that stance doesn’t mean that I think there is no principled way to pick sides.

Instead of the lengthy, nuanced argument most academics would give, the story of Norman Morrison provides a quick method for deciding which side you’re on.

Morrison was a part of the aggressive activism in the ‘60s against the war in Vietnam. Most of us are aware of some of this activism: the marching in the streets, the blocking of military recruiting sites, and the burning of draft cards. More violent forms of protest also existed, including assaults against law enforcement, vandalization and burning, and breaking into military offices to destroy and steal documents.

But Morrison’s act went beyond all of these. He practiced a form of less well-known anti-war activism by imitating the acts performed by a number of communist-sympathizing Buddhist monks in South Vietnam.

A young Quaker with a wife and three children under the age of six, Morrison was described by his wife as someone who cared deeply about people in the abstract, but who was ill at ease with actual human beings. On Nov. 2, 1965, he went to the Pentagon with infant daughter, Emily, without telling his wife of his plans. There, after either setting Emily down or handing her off to a stranger, he used a can of kerosene to fatally set himself ablaze. All this in the belief, apparently, that immolating himself and perhaps also his child would strike a blow on behalf of the Vietnamese children who had died during the war.

Morrison’s oldest daughter, Christina, summarized the heart-breaking effect of her father’s action, noting that “It didn’t stop the war,” and it made the people of Vietnam seem “more important” than her family.

I was incensed that he could even imagine sacrificing a child in following his own vision. And he did sacrifice her in a sense by requiring her to witness his death and by leaving her there without him. … I have often felt that, in a sense, my father sacrificed all five of us in hopes of saving the people of another country.

The logic of Morrison’s deed follows from his political and social principles, and those principles were accepted by many in the streets in the ‘60s who might have seemed quite less radical than he. They believed the U.S. war effort in Vietnam was evil and that the communist cause was justified as resistance to that evil. They believed that any consistent advocate for justice, in a land so distant from the site of the violent consequences of imperialist evil, had to be prepared to sacrifice themselves and those close to them to fight against such evil being done to those distant peoples.

Here you have your basic 1960s moral calculator.

If you agree with Morrison, and you find his self-annihilation and abandonment of his wife and young children an admirable and morally sound symbolic contribution to the anti-war effort, you are on one side. If you see what he did as a horrifying atrocity, and you believe it a dangerous delusion to be more committed to the well-being of abstractions in your mind that represent people on the other side of the planet you’ll never know than you are to the children of your own flesh, you’re on the other.

Essentially, the ‘60s as a whole can be boiled down to these two simple principles. In many ways, this dichotomy is applicable to our own time as well.

Are your moral concerns most intensely focused on those closest to you, perhaps radiating outward beyond kin and community, but inevitably weakening as they move outward? Or are they focused with equal intensity everywhere, or perhaps—owing to the requirements of social justice—especially concentrated on expert-approved victim populations, regardless of their distance from you, your loved ones, and the community in which you live? Indeed, regardless of whether you will ever see them?

Answer that and know where you stand.

—

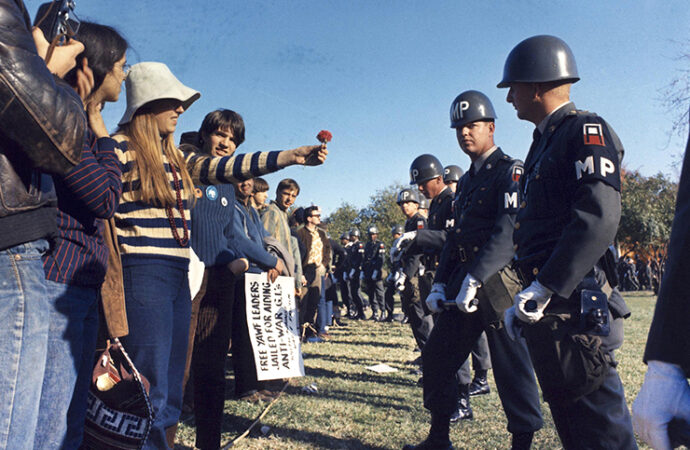

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons-S.Sgt. Albert R. Simpson, U.S. Army. Public Domain.

1 comment

1 Comment

ellyse hix

April 25, 2025, 6:59 amFor students in Australia struggling with complex financial topics, <a href="https://au1.globalassignmenthelp.com.au/accounting-assignment-help">Accounting Assignment Help Australia</a> has been a great resource—offering clear explanations and expert guidance. Also, I highly recommend using a <a href="https://au1.globalassignmenthelp.com.au/grammar-checker">Grammar Checker</a> before submitting any assignment. It helps polish your writing and ensures your work is error-free and professional. These two tools together can really boost your academic performance.

REPLY