When totalitarian regimes (particularly those of the Left) come to power, one of the first things they typically do is destroy hallowed cultural symbols, the better to remake society from the ground up. The Soviet campaign to replace the symbols of Christmas is an interesting cultural chapter in the history of what Ronald Reagan famously called the “Evil Empire.” It is discussed here.

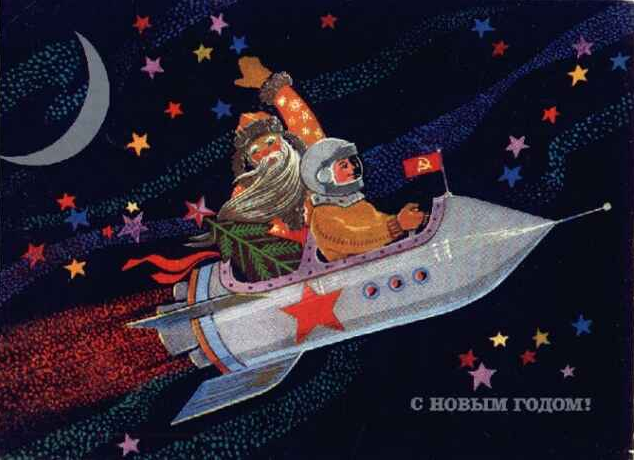

Following the Russian Revolution, the new atheist government began an anti-religious campaign. All symbols deemed religious and/or “bourgeois” were eradicated and replaced with new, secular versions. Thus Christmas (which in the Russian Orthodox calendar occurs on January 7) was abolished in favor of New Year’s, and several traditional Christmas traditions and characters received new identities. St. Nicholas/Santa Claus gave way to Ded Moroz or “Old Man Frost” (a popular figure originating in pagan times), and the new “nativity scene” featured him and his granddaughter the Snow Maiden in place of Joseph and Mary, sometimes with the “New Year Boy” added in place of Jesus. Christmas cards often featured Ded Moroz riding alongside a Soviet cosmonaut in a spacecraft emblazoned with a hammer and sickle.

Such images seem laughable now, but the impulse to destroy tradition is part and parcel of radical social movements throughout history. Think of the French Revolutionaries, who replaced the Christian calendar with a naturalist one, and even renamed the months and the days of the week so as to avoid any possible reference to Christianity.

And the Soviets weren’t the only ones to have a problem with Christmas. The Puritans of seventeenth-century Boston were vehemently against it too. A “Publick Notice” from the period survives proclaiming the following:

“The Observation of Christmas having been deemed a Sacrilege, the exchanging of Gifts and Greetings, Dressing in Fine Clothing, Feasting and similar Satanical Practices are hereby FORBIDDEN with the Offender liable to a fine of five shillings.”

The one group hated Christmas because it was religious, and the other hated it because it was irreligious. History, and human nature, are full of paradoxes.

As for the Soviets, they eventually softened their stance. In 1935 the Communist Party official Pavel Postyshev wrote an editorial in Pravda mocking the extreme anti-Christmas faction. He declared that Christmas customs ought to be brought back for the enjoyment and benefit of children. (Needless to say, the goal vis à vis the children was always to make them obedient servants of the state.) After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Christmas became popular again.

All of which goes to show that while you can fight against tradition, you can’t utterly destroy it. It may go underground, it may lie dormant, but once restrictions are lifted it will spring forth to new life. And any regime which tries to replace the familiar world with a synthetic one is fundamentally at war with the human spirit.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *