Edward Bernays is often referred to as the “father of public relations” and was one of the great proponents of propaganda in the 20th century.

According to his biography, “During World War I, he was an integral part – along with Walter Lippmann – of the U.S. Committee on Public Information (CPI), a powerful propaganda machine that advertised and sold the war to the American people as one that would ‘Make the World Safe for Democracy’.” After the war, he turned his talents to building a business of public relations and propaganda. “Among his powerful clients were President Calvin Coolidge, Proctor & Gamble, CBS, the American Tobacco Company and General Electric.”

Bernays defined propaganda as “a consistent, enduring effort to create or shape events to influence the relations of the public to an enterprise, idea or group.” And in his opinion it was necessary in a modern society.

The new propaganda, having regard to the constitution of society as a whole, not infrequently serves to focus and realize the desires of the masses. A desire for a specific reform, however widespread, cannot be translated into action until it is made articulate, and until it has exerted sufficient pressure upon the proper law-making bodies. Millions of housewives may feel that manufactured foods deleterious to health should be prohibited. But there is little chance that their individual desires will be translated into effective legal form unless their half-expressed demand can be organized, made vocal, and concentrated upon the state legislature or upon the Federal Congress in some mode which will produce the results they desire. Whether they realize it or not, they call upon propaganda to organize and effectuate their demand.

In his thinking, Bernays saw that neighbors and communities are no longer united in beliefs as they often were in the past. In a nation of hundreds of millions of people, many millions may share similar beliefs but live miles apart. Without propaganda how can they unite and express those beliefs?

Of course, as Bernays admitted, there would always have to be small groups driving the propaganda campaigns. And those groups wouldn’t always agree.

But clearly it is the intelligent minorities which need to make use of propaganda continuously and systematically. In the active proselytizing minorities in whom selfish interests and public interests coincide lie the progress and development of America. Only through the active energy of the intelligent few can the public at large become aware of and act upon new ideas.

Small groups of persons can, and do, make the rest of us think what they please about a given subject. But there are usually proponents and opponents of every propaganda, both of whom are equally eager to convince the majority.

As he put it later in Propaganda, “The great political problem in our modern democracy is how to induce our leaders to lead.”

It’s a powerful, though disturbing, argument. In a society in which only geography and a loose agreement about social norms unites people, is propaganda a necessary force? Can it be a good thing?

—

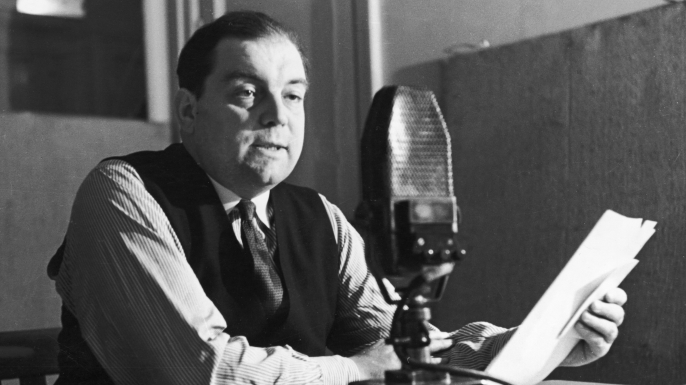

Image Credit:

Sefton Delmer, History Channel

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *