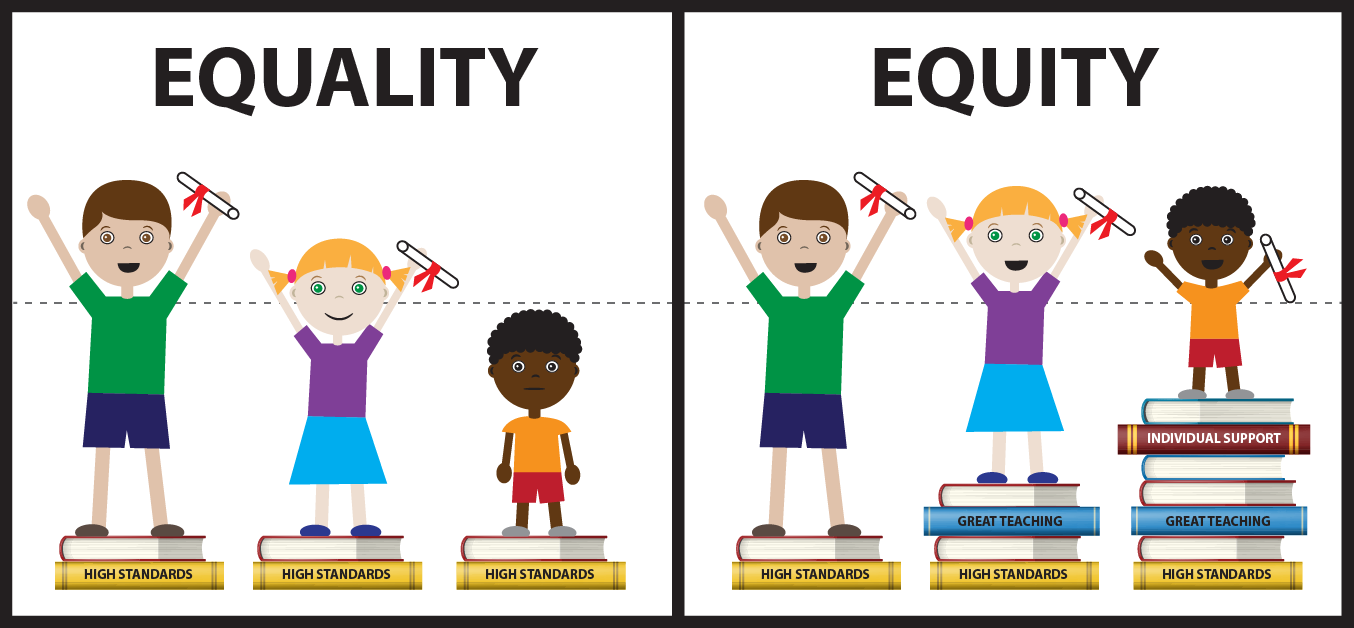

Particularly in education, there’s been a shift in terminology away from ‘equality’ and towards ‘equity’. You may have noticed it in the media, on campuses, or in political discussions. Often, a graphic like the one below is used to show the difference:

The image above is similar to other images being used around the country, with this one coming from the Georgia Education Equity Coalition. As the site argues:

“Since every child in is being asked to meet higher standards, states and school districts have an obligation to provide every resource necessary to teachers, schools, and parents so that children meet the standards. Parents and local leaders must be at the forefront of advocating for equity and holding school systems accountable to ensuring every child graduates college-and-career-ready.”

Essentially, what the equity movement admits is that providing equal resources does not result in equal outcomes. In doing so, they admit that equal opportunity is impossible. To create equal outcomes, equity is required.

In some ways, the graphic alone reminds one of the idea made most famous by Karl Marx:

“From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!”

The Georgia Education Equity Coalition seems to believe that the white male doesn’t need “great teaching” or “individual support”, while the black male does. Surely, a few people will take offense to such a declaration. As this movement continues to make inroads into influencing public education in America, there will likely be more and more attention on the issue and the flaws in the thinking as well as its radical nature will become more visible.

Consider the story out of Australia earlier this year about a philosopher bemoaning the fact that parents who read to their kids give them an unfair advantage in school and life.

“The power of the family to tilt equality hasn’t gone unnoticed, and academics and public commentators have been blowing the whistle for some time. Now, philosophers Adam Swift and Harry Brighouse have felt compelled to conduct a cool reassessment.

Swift in particular has been conflicted for some time over the curious situation that arises when a parent wants to do the best for her child but in the process makes the playing field for others even more lopsided.

…

Once he got thinking, Swift could see that the issue stretches well beyond the fact that some families can afford private schooling, nannies, tutors, and houses in good suburbs. Functional family interactions—from going to the cricket to reading bedtime stories—form a largely unseen but palpable fault line between families. The consequence is a gap in social mobility and equality that can last for generations.

So, what to do?

According to Swift, from a purely instrumental position the answer is straightforward.

‘One way philosophers might think about solving the social justice problem would be by simply abolishing the family. If the family is this source of unfairness in society then it looks plausible to think that if we abolished the family there would be a more level playing field.’”

Again, the goal is to have equal outcomes; simple equal opportunity is no longer attainable in the minds of many academics and activists.

What seems to be willfully ignored is the possibility that equal outcomes (equity) are likely to be impossible, too, because of the same complexities of the human person that make equal opportunity impossible.

F.A. Hayek, the author of The Road to Serfdom, saw this problem even with the equal application of the laws:

“It cannot be denied that the Rule of Law produces economic inequality…”

And that is because people are fundamentally unequal through genetics, how they were raised, the language of their people, life experiences, the circumstances of their living such as geography, etc. We could give 10 different people $100,000 in the name of equal opportunity. It’s doubtful that after even one day that those 10 different people would remain in an equitable economic state. The same is true for education. We can give children the opportunities to learn, but that does not mean they actually will learn. There’s truth to the old adage, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink.”

For those who push for equity, the same questions that dogged Marxism must be answered. Who will be the arbiter of taking from some and giving to others? Who can account for all of the variables of the human experience necessary to create a perfectly equitable society? Who will determine the hierarchy of needs? How quickly will things be readjusted to maintain equal outcomes? What steps will be necessary to ensure those equal outcomes? How much force will be required? Is freedom even possible in such an environment?

Of course, not only should we question the mechanics of equal opportunity and equity, but we should also question whether or not equality should be the organizing principle of our society. What in human history indicates that everyone wants to be the same or should be the same?

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *