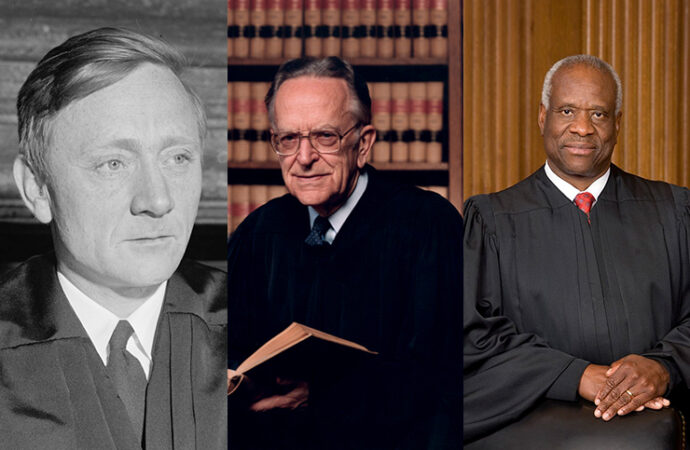

The final three justices in this Supreme Court series bring us from 1939 to the present.

7. William O. Douglas (April 17, 1939 – November 12, 1975)

Appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to succeed Justice Louis Brandeis, Douglas was confirmed by the Senate in a 62-4 vote. He served with Justice James Clark McReynolds for just under four years.

Douglas matched FDR’s liberal bent. As Berkeley Law Professor Christopher Tomlins wrote, Douglas “did not rank consistency and stare decisis highly among his legal principles and sought instead to decide each case in relation to its social, political, and economic context.” Yale Law Professor Steven Duke noted that many of Douglas’ published opinions “were drafted in twenty minutes” which led to them “often read[ing] like rough drafts.”

His opinion in Griswold v. Connecticut resonates today, in which a newly discovered “right of marital privacy” was the majority’s basis for striking down a Connecticut law barring individuals from using contraceptive drugs or devices. Douglas wrote that “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.” (Penumbras being rights supposedly implied by other rights that are explicitly protected in the Constitution.) The privacy right found by the Court’s Griswold decision would lead to Roe v. Wade, and the enumeration of penumbras is a succinct definition of the living Constitution philosophy carried by many today.

Douglas also argued in Sierra Club v. Morton that inanimate objects have standing to sue.

Inanimate objects are sometimes parties in litigation. …

The river, for example, is the living symbol of all the life it sustains or nourishes—fish, aquatic insects, water ouzels, otter, fisher, deer, elk, bear, and all other animals, including man, who are dependent on it or who enjoy it for its sight, its sound, or its life. The river as plaintiff speaks for the ecological unit of life that is part of it.

Always at the center of controversy, Douglas’ attempt to issue a stay of execution for Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg resulted in a brief but unsuccessful impeachment attempt. Douglas also turned against the Vietnam War after the South Vietnamese president was assassinated in 1963, forcing his eight fellow justices to twice overturn his attempts to declare the war illegal.

Douglas’ salacious lifestyle put him at odds with then-House Minority Leader Gerald Ford, leading to a second attempt to impeach Douglas based on connections to gamblers and his authorship of articles in magazines which published pornographic material.

Douglas retired on November 12, 1975, having served more than 36 years, longer than any other justice.

8. Harry Blackmun (June 9, 1970 – August 3, 1994)

Harry Blackmun was appointed by President Richard Nixon and was confirmed by the Senate in a 94-0 vote, serving alongside Douglas for more than five years. Despite an initially conservative record, Blackmun became a decidedly liberal member of the court.

For example, Blackmun was personally opposed to the death penalty, yet for much of his tenure he didn’t allow that view to affect his view of the policy’s constitutionality, voting to uphold it in his dissent to Furman v. Georgia and voting to reinstate it in the court’s Gregg v. Georgia decision. He reversed course later, writing in his dissent to Callins v. Collins:

From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death. … I feel morally and intellectually obligated simply to concede that the death penalty experiment has failed.

Ironically, the most famous opinion of a justice so concerned to “no longer… tinker with the machinery of death” is Roe v. Wade. This case extended the right to privacy introduced by Douglas to a Constitutional protection for abortion. In his opinion for the court Blackmun wrote:

Although the results are divided, most of these courts have agreed that the right of privacy, however based, is broad enough to cover the abortion decision; that the right, nonetheless, is not absolute, and is subject to some limitations; and that, at some point, the state interests as to protection of health, medical standards, and prenatal life, become dominant. We agree with this approach.

Where certain ‘fundamental rights’ are involved, the Court has held that regulation limiting these rights may be justified only by a ‘compelling state interest.’

Blackmun became rather obsessed with the issue of abortion rights, bringing Roe into his reasoning on cases which had little to no relation with abortion, such as in Michael M. v. Superior Court of Sonoma County, which dealt with gender biases in statutory rape laws.

Blackmun retired on August 3, 1994, after more than 24 years on the court.

9. Clarence Thomas (October 23, 1991 – Present)

Nominated by President George H. W. Bush and confirmed in a 52-48 Senate vote, Thomas served alongside Blackmun for nearly three years. He succeeded Thurgood Marshall, making him the second African-American justice on the Supreme Court.

The close margin in Thomas’ confirmation battle followed allegations of sexual misconduct by Anita Hill, which Thomas at the time referred to as “a high tech lynching for uppity blacks who in anyway deign to think for themselves… and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order this is what will happen to you.”

Thomas is an originalist, believing the Constitution must by interpreted based on a plain understanding of the Constitution as it is written, and abhorring the living view of the document taken by justices such as Douglas and the latter part of Blackmun’s tenure on the court. Thomas reportedly even has a sign in his office mocking Douglas’ Griswold opinion. The sign reads “Please don’t emanate in the penumbras.”

Thomas tends to take a broad view of those rights directly enshrined in the Constitution’s text, such as in Citizens United v. FEC, where he voted with the majority, but issued a split concurrence/dissent from Part IV, arguing the Court should have gone further and struck down more campaign contribution limitations in view of the First Amendment.

He has repeatedly argued that the 14th Amendment forbids consideration of race in programs such as affirmative action in hiring processes or college admissions. Concurring in Gratz v. Bollinger Thomas wrote, “I would hold that a State’s use of racial discrimination in higher education admissions is categorically prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause.”

An ardent critic of the Roe decision, Thomas has used every possible opportunity to restate his belief that the case was wrongly decided and ought to be overturned. His concurring opinion in Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. lays out abortion’s history with the eugenics movement, noting that states have a “compelling interest in preventing abortion from becoming a tool of modern-day eugenics.” Thomas also recently signaled a potential willingness to overturn the Obergefell v. Hodges decision which legalized gay marriage.

—

William Cushing. John Marshall. James Moore Wayne. Stephen Johnson Field. Edward Douglass White. James Clark McReynolds. William O. Douglas. Harry Blackmun. Clarence Thomas. The overlapping tenures of these nine men span the entire 231-year history of the Court.

In essence, only eight degrees of separation exist between George Washington’s first Supreme Court appointees and the current Court partially staffed with appointees of Donald Trump.

The longevity of these justices and the impact of their decisions are what makes their seats so critical. It is why Trump is eager to see Amy Coney Barrett seated, and why Democrats are so desperate to make sure the court does not tilt against their ideology for decades to come.

—

This is part three of a three-part series on the history of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Part One: Foundation and Secession

Part Two: Reconstruction and Court Packing

Image Credit:

Left-Wikimedia Commons-Library of Congress-Harris & Ewing, public domain. Center-Wikimedia Commons, public domain. Right-Wikimedia Commons-Steve Petteway, public domain.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *