After months of violent demonstrations – especially in New York, Seattle, Minneapolis, and Portland – many Americans might not want to learn of yet another. This one, however, dates back long before any living person’s memory and ranks as the worst ever on the grounds of the White House in Washington. The issue, believe it or not, was a bank.

That’s right, a bank. Not racism. Not corruption. Not even an unpopular war. The mob that broke windows and nearly stormed the residence of the highest U.S. official in August 1841 demanded a government-sponsored central bank from a president who refused to give them one. Here’s the story.

The 1840 election pitted incumbent Jacksonian Democrat Martin van Buren against Whig Party challenger and Battle of Tippecanoe hero William Henry Harrison. Four years earlier, Harrison had lost to Van Buren but this time he prevailed. His running mate was former Democrat John Tyler of Virginia, giving rise to the famous campaign slogan, “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!”

Harrison assumed the presidency on March 4, 1841 at the age of 68. He term-limited himself by dying just 31 days later. The Whigs expected Tyler to faithfully implement the big-government Whig program designed by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay but were quickly disappointed. Even as the party’s vice-presidential candidate, Tyler never disguised his skepticism for Clay’s schemes of a central bank, corporate welfare and high tariffs.

Clay ran the Senate and his fellow Whigs controlled the House, where Clay had previously served a decade as Speaker. While president Tyler cautioned against creating a new central bank (Andrew Jackson had killed the last one a few years before), Clay pressed forward with it in the summer of 1841. A bank bill passed both houses and went to Tyler’s desk, where it died by veto on August 16. The president regarded it as unconstitutional in part because it would force the states to accept branches of the central bank within their boundaries, in direct competition with state-chartered banks.

Tyler began his veto message by reminding Congress that his opposition to a federal bank was longstanding. For 25 years, he pointed out, he expressed this view as a state and federal legislator. He had just sworn an oath to preserve, protect and defend the very Constitution that Clay’s bank scheme would undermine. To turn his back now on both the Constitution and his own conscience, wrote Tyler, “would be to commit a crime which I would not willfully commit to gain any earthly reward, and which would justly subject me to the ridicule and scorn of all virtuous men.”

A central bank would enhance the power of the federal government at the expense of the states, bestow benefits on a financial elite, and undermine the cause of sound money. Tyler wisely wanted nothing to do with it.

The Whigs erupted in a fury of indignation. In his biography of Tyler, historian Gary May describes what happened next:

At 2:00 a.m. on the morning of August 18, a drunken mob gathered outside the White House portico. They blew horns, beat drums, threw rocks at the building, and fired guns into the night sky. Tyler and his family were awakened by the noise…Someone in the mansion’s upstairs quarters lit candles and the light scared the crowd off. Another group arrived a few hours later, dragging a scarecrow-like figure. They set it afire and John Tyler was burned in effigy. It was the most violent demonstration ever to occur at the White House complex.

Security at the executive mansion was minimal in those days. It was not uncommon, in fact, for visitors to walk right in unescorted. A drunken painter even threw rocks at President Tyler as he walked the south grounds. When an odd-looking package arrived by mail at the White House, Tyler feared a bomb, but it fortunately turned out to be a cake.

Clay urged the Senate to override the president’s veto but he failed to get the required two-thirds vote. A new central bank bill with minor adjustments then passed both houses. On September 9, Tyler vetoed that one too. The second veto prompted a stream of invective from Whig-friendly media that lasted for the rest of Tyler’s term. From May’s biography again:

‘If a God-directed thunderbolt were to strike and annihilate the traitor,’ the Lexington Intelligencer wrote, ‘all would say that “Heaven is just.”‘ Tyler was called ‘His Accidency’; the ‘Executive A**’; ‘base, selfish, and perfidious’; ‘a vast nightmare over the republic.’ One writer claimed that the president was insane, the victim of ‘brain fever.’ Another, borrowing from Shakespeare, called ‘for a whip in every honest hand, to lash the rascal naked through the world.’ There were anti-Tyler rallies and demonstrations everywhere and numerous burnings in effigy, including in Richmond and at the Charles City County courthouse, where the young John Tyler had practiced law. Angry letters poured into the White House; many proffered threats on the president’s life. What happened next was also expected, but it was still shocking because it had never before happened in American history: the president’s entire cabinet, save [Secretary of State] Daniel Webster, resigned.

On Monday, September 13, angry congressional Whigs formally expelled President Tyler from their ranks. Henry Clay pronounced to his political comrades that Tyler was “a President without a party.” Unlike the opportunistic and ambitious Clay, Tyler was a man of steadfast principles – and those are things that too many politicians (then and now) neither possess themselves nor can abide in others.

Whig vitriol dogged Tyler for the remainder of his term. In the months after the bank vetoes, he also nixed Whig bills to hike tariffs. In response, his congressional opponents formed the first-ever committee to explore whether the president should be impeached and named former president John Quincy Adams as its chair. Its final report, released on August 16, 1842, concluded that Tyler had committed “offenses of the gravest character” and deserved to be impeached. Fearing a political backlash in the country, the committee’s majority stopped short of recommending it.

The report of the Adams committee was partisan political theater at its worst. Tyler had done utterly nothing impeachable. His “offenses of the gravest character” amounted to nothing more than failure to advance the flawed big government agenda of Henry Clay and the Whig Party.

A few years later when Clay realized his own life-long lust for the presidency would never materialize, he famously declared in a speech to the Senate, “I would rather be right than be President.” Time and again, he was neither.

So a firestorm in the Congress produced a riot at the White House. It was all about a bank which the country did not need and which the president rightly used his constitutional authority to thwart. By any measure, it was not our finest hour. But Tyler’s vetoes stand, in my view, as great moments in presidential courage.

One final note regarding President John Tyler: His two grandsons are still around today, at ages 96 and 92. It sounds incredible that two men are living right now whose grandfather was President of the United States almost 180 years ago. You can read the details here.

—

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

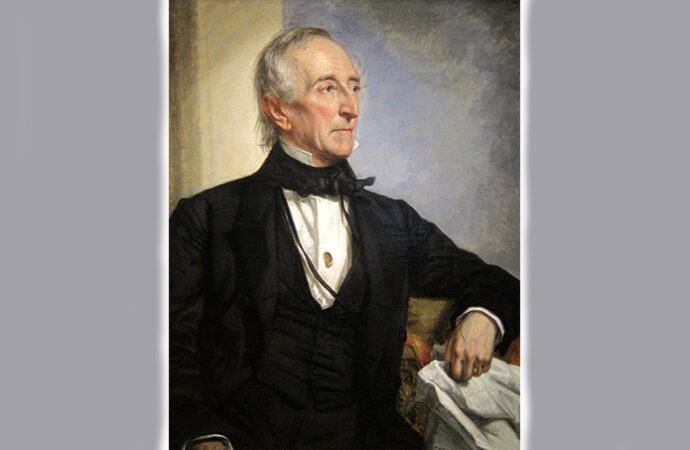

Image Credit:

Wikimedia Commons – George Peter Alexander Healy, public domain, modified

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *