During the Great Recession, President Obama’s chief-of-staff Rahm Emanuel infamously advised, “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.” And, sure enough, the COVID-19 threat has given politicians another crisis to promote long-sought policy goals. Some are calling for a modern version of the New Deal, but is this a good idea?

Setting the Stage for Big Government

Conventional wisdom long held that the New Deal saved the economy and ended the Great Depression. That narrative has come under increasing scrutiny. But either way, what everyone can agree on is that the New Deal established precedents for our modern, enormously powerful, and intrusive federal government.

Before the New Deal, the federal government’s role in daily life was scant. Government regulations for the economy were almost exclusively handled by state and local governments through their “police power.” Originally understood, the police power allowed state and local governments – but not the federal government – to prevent individuals and businesses from invading the rights of others (think of a public nuisance) and to regulate rightful conduct (for instance, requiring certain formalities to properly record sales of real estate).

Now, the federal government wields vast power and touches almost every aspect of daily life. How did we get here?

The Great Depression, the Government’s Response, and the Supreme Court’s Approval

The Great Depression caused widespread misery, but unlike previous economic downturns, this time the American people largely called for the federal government to “do something.” FDR wasted no time. Just two days after taking the oath of office, he declared a national banking holiday, dubiously claiming authority under the Trading With the Enemy Act of 1917. The New Deal experiments had begun, and FDR raced from program to program – opening offices here, establishing committees there, reorganizing departments throughout – hoping to stem the deepening depression.

These efforts were initially stymied by a Supreme Court that still hewed to the Constitution, which delegated only a few, enumerated powers to the federal government. According to the Constitution, the federal government was authorized to make policy only for the “general welfare” – that is, only for matters that were truly national in scope, things like the military or the nation’s borders. The Constitution does not grant the federal government a general police power to regulate private business or farming or manufacturing.

But eventually, after FDR threatened to pack the Court, the Supreme Court upheld laws allowing the federal government to regulate labor relations of private companies, fix prices for various goods, and establish minimum wages in private industry. The Supreme Court held that the federal government could even prevent a farmer from growing wheat solely for his family’s consumption, on the grounds that the farmer’s actions indirectly affected interstate commerce.

The Federal Government Only Expands

When the “emergency” of the New Deal (and World War II) subsided, some programs lapsed. But the notion that the federal government has a large, active role in our economic life stuck. The key features of the New Deal – aspects like the Fair Labor Standards Act – continue to control private industry. These laws are updated from time to time, and government itself continues to insist that its involvement is vital to the nation’s economic health.

Let’s look at a concrete example of a New Deal legacy that remains timely – housing. As a report from the Congressional Research Service shows, the New Deal inserted the federal government into the housing market in an unprecedented fashion. Before the Great Depression – what the report calls the “early years” – the federal government’s role in housing consisted of an investigation of city slums (1892), reports to a presidential housing commission (1909), and two WWI-era policies (loans for shipyard workers’ housing and housing for “war workers”).

With the onset of the Great Depression, however, the federal government created countless commissions and committees, injected federal dollars into housing projects (Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932), guaranteed and directly provided loans for housing (Federal Home Loan Bank Act of 1932), and continued to adopt housing laws, amend existing laws, and reorganize the growing federal bureaucracy.

For example, the government’s housing policy increased in the Housing Act of 1949, which declared that “the general welfare” and “security” of the country “require” housing production and “related community development” to “remedy” housing shortages, substandard and inadequate housing. The pervasive nature of the problem is exemplified by the Federal Housing Administration, an agency created by the National Housing Act of 1934 and which today is the “largest mortgage insurer in the world.”

Failure Is Not an Option

The New Deal’s constant experimentation has encouraged only more government involvement in people’s daily lives. Any failure to “solve” the various problems is blamed on market failure, which we are told only government can fix.

Take the affordable-housing crisis. Many years ago, the California Legislature declared housing to be “of vital importance” and adopted various programs to solve the affordable-housing problem. Yet, in a recent decision, the California Supreme Court lamented that – despite the efforts of government – “the significant problems arising from a scarcity of affordable housing have not been solved over the past three decades. Rather, these problems have become more severe and have reached what might be described as epic proportions in many of the state’s localities.”

Courts now routinely uphold these government experiments – as the California Supreme Court did here – and leave Americans progressively less able to order their own affairs.

The calls for a new New Deal should be resisted. We should not let politicians use this crisis for their benefit.

—

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

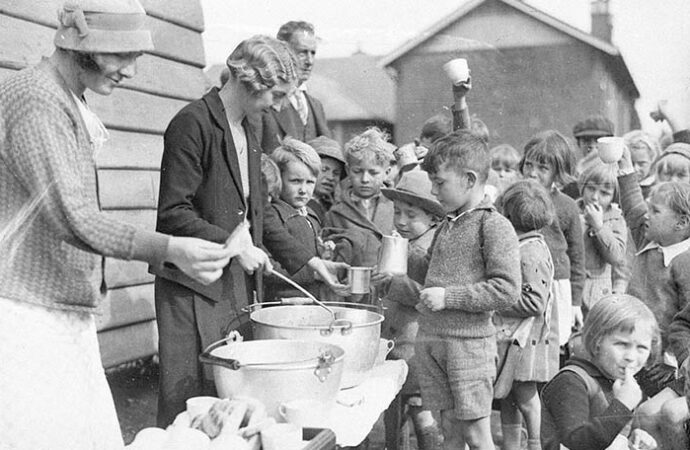

[Image Credit: Flickr-State Library of New South Wales, no known copyright restrictions]

Image Credit: [Image Credit: Flickr-State Library of New South Wales, no known copyright restrictions]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *