With Sigmund Freud, the Swiss psychologist Carl G. Jung (1875-1961) pioneered studies of the human unconscious. After he famously rejected Freud’s views on religion and sexuality, he undertook a lifelong investigation of dreams, symbols, and archetypes to tie modernity to age-old images and traditions. What the human psyche craves are faith, hope, love, and insight. Jung thought these were achieved through experience, not formal instruction.

The Age of Enlightenment had “stripped nature and human institutions of gods,” Jung professed, bestowing rationality and wealth but neglecting core elements of human satisfaction. To dismiss the soul as illusion was to miss something big. “Instead of being at the mercy of wild beasts, earthquakes, landslides, and inundations,” Jung said, “modern man is battered by the elemental forces of his own psyche,” destabilized by unfulfilled spiritual yearnings.

The notion that Jung became a solitary man of genius after his break with the psychoanalytic movement in 1913 is false. He remained highly connected, a prolific writer with global renown that has never lapsed. His impact on German novelist Hermann Hesse was profound. From the time of his Harvard seminars and Yale lectures in 1936 and 1937, he drew a number of highly accomplished American admirers. He appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1955. During the early, intellectualizing counterculture, Jung’s metaphysics harmonized with the humanistic revolt against technocratic, secularizing society. Technology dulled instincts, Jung feared.

Jung sharply rejected Freud’s outlook on religion and sexuality. For Freud, religion was illusion and superstition, but for Jung it was a wondrous manifestation of human nature and ineffable soul. “How are we to explain this zeal, this almost fanatical worship of everything unsavory?” Jung once asked. Freud “has taken the greatest pains to throw as glaring a light as possible on the dirt and darkness and evil of the psychic background.” The outcome of Freud’s preoccupation with aggression and sexuality, Jung decided, was not catharsis but “admiration for all this filth.” For Jung, the unconscious was more than a repository of suppressed will and lust. The libido was closer to Henri Bergson’s life force, a sunnier view of human nature and personality than Freud allowed.

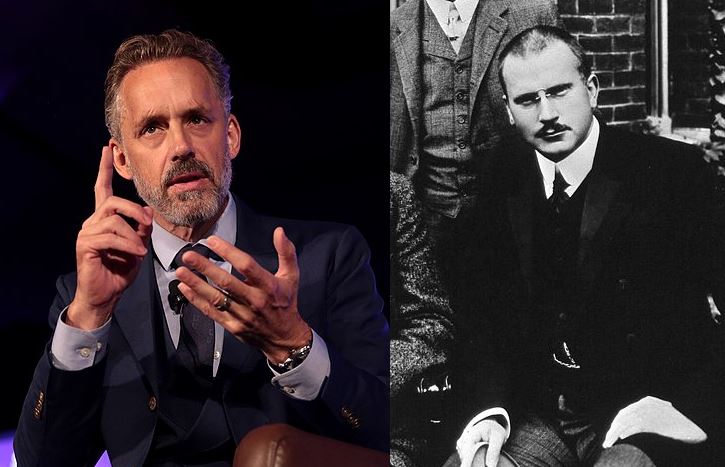

“For a young person, it is almost a sin, or at least a danger, to be too preoccupied with himself,” Jung insisted. You must detach from loving parents, go out and do something, make a life. Thus, inspecting the stages of life, Jung precedes his most prominent contemporary student, psychologist Jordan Peterson. Elemental cravings—faith, hope, love, and insight—equally concern Peterson, whose sensationally popular book, 12 Rules for Life, is exposing a new generation to Jungian concepts.

The profuse number of man-children and wounded women in a never-grow-old culture indicates something terribly socially amiss—on that, Jung and Peterson agree. Charmless slackers and baristas who seem so often to have grown up with absent fathers or in odd, blended families are liberated from tradition and canon but feckless and lonely. Neurotic efforts, said Jung, to extend youthful conquests and an endless horizon continue “beyond the bounds of all reason” into middle age and beyond. Conversely, the old, instead of pursuing “illumination of the self,” turn into hypochondriacs and adventurers.

Through dream analysis and arcane studies, Jung investigated themes and symbols that constitute “identical psychic structures” common to all cultures. Comparing age-old myths, fables, and sacred figures provides a grammar or code to understand the imperatives of human nature. To cope with the world, said Jung, individuals might present a polished, conscious persona. Yet the unconscious—the “shadow” or “dark side”—might make anyone feel stupid, gauche, vulnerable, or evil. There’s extraversion, talkative and energetic, and introversion, reserved, solitary, and contemplative. The mathematician, editorialist, connoisseur, and visionary might be equally brilliant but each has distinct preferences, strengths, and behaviors. These different personality types might also have difficulty understanding, validating, and cooperating with one another.

Jung has many adversaries. Postmodernists reject his Bildung view of civilization, rooted in European learning and scholarship, expressing its ambitions in complex thought, literature, music, fine arts, and science. Christians don’t like his syncretism. Jungian insiders can be clubby, precious, and tedious. In a takedown of Jordan Peterson, the New Republic’s Jeet Heer called Jung’s collective unconscious “a speculative netherworld that defies empirical verification.” Heer speaks for those who think Jung is a mystic or charlatan. Jung can be cryptic, ecstatic, and strange. Even Jordan Peterson—who is a bit strange himself—admits that.

Many years ahead of his time, Jung perceived the ontological void that accompanied Christianity’s recession. Waning spiritual power induced the rise of unstable, insecure, and suggestible masses, he warned, hobbled with debilitating feelings of insignificance, inadequacy, and hopelessness. When “earth was eternally fixed and at rest in the center of the universe,” he said, people “were all children of God” who knew the path to “eternal blessedness” and “joyous existence.” Such a “life no longer seems real to us, even in our dreams.”

One of Jung’s best-known works, Modern Man in Search of a Soul (1932), collects 11 short essays that outline concepts he elsewhere elaborates on at length. The collection contains “The Spiritual Problem of Modern Man,” one of his most celebrated articles, which first appeared in the December 1928 issue of Europa¨ische Revue. Here Jung developed his most explicit analysis of “modernity.”

As for many Europeans of Jung’s generation, what he called the “catastrophic results” of the First World War “shattered faith in ourselves and our own worth.” The Bolshevik revolution in Russia stirred panic among Central Europe’s cultivated bourgeois, and Weimar antics colored the scene. Before Adolph Hitler or Hiroshima, Jung said, “I am losing my faith in the possibility of a rational organization of the world,” and “as for ideals, neither the Christian Church, nor the brotherhood of man, nor international social democracy, nor the solidarity of economic interests has stood up to the acid test of reality.”

Jung disdained the “pseudo-modern” who exhibits “ineradicable aversion to traditional opinions and inherited truths.” Modern for Jung would not be a Google virtual reality coder or a psychedelic conga line at Burning Man. He insisted that the genuinely new sprang from profound familiarity with the past, not from know-nothing condemnation of it. New ideas are always alarming, he understood, and modern thinkers from Socrates to Galileo to Nietzsche disturbed the conformative equilibrium even while anchored to history and culture. To the falsely modern individual, who “wants to experiment with his mind as the Bolshevik experiments with economics,” Jung said, “all the spiritual standards and forms of the past have somehow lost their validity.”

For decades now, throughout the U.S. and Europe, pseudo-modernity has hypertrophied. For liberated individuals young and old, the self is a preoccupation. I’m not here to make friends; I’m here to win. Wellness and entertainment fill any void. Cosmetic surgery bears no stigma. Marketers with complex proprietary information and irresistible electronic tools at their disposal do their best to reshape the collective unconscious, often with a libertine edge.

Jung has been accused of anti-Semitism and fascist sympathies, perceived as a right-wing shadow figure by his enemies, as has Jordan Peterson more recently. In early psychoanalytical circles, Jung had been a Protestant among Jews. After his break with Freud, he observed in private letters what he took to be general Jewish personality traits, including aggression and hypersensitivity to criticism. He disapproved of Judaism’s role in the secularization of modern life. Yet Jung thought Freud and his circle “accused me of anti-Semitism because I could not abide his soulless materialism.”

The Nazi sympathies are confected. Jung operated as an analyst and informer for the U.S. Office of Strategic Services during the Second World War. Called Agent 488, he worked with Allen W. Dulles, brother of John Foster Dulles and later the first director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Dulles later said, “Nobody will probably ever know how much Prof. Jung contributed to the allied cause during the war.” Jung was not essentially political. His attachment to learned, liberal European culture was profound. His primary interests were the interior life and psyche, human and cosmic longings, and the ability of civilization to survive modernity.

—

This article has been republished with permission from The American Conservative.

[Jordan Peterson Image Credit: Flickr-Gage Skidmore CC BY-SA 2.0]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *