It was the sinking of a British boat by a German torpedo that began to push the United States toward entering World War I.

For many Americans the attack on the ocean liner Lusitania in May 1915 and the subsequent death of an estimated 1,198 people including 128 Americans solidified the belief that Germany was a brutal, degenerate monarchy.

It would take another two years for the U.S. to declare war on Germany but after this event more Americans began to speak out in favor of joining the conflict on the Allies’ side.

By any measure, the torpedoing of the Lusitania was abhorrent.

But there is also a story behind the story, as our research for a forthcoming book on World War I propaganda shows, and that story provides one of our earliest examples of the effective – and ineffective – deployment of a weapon that was as new in World War I as submarine warfare: government propaganda.

New departures in naval warfare

World War I was unprecedented in many respects and that included its conduct on the sea.

From the outset of the war in August 1914, the British imposed a blockade that was legally dubious because it extended over the entire North Sea, not an area of actual fighting.

This prevented not only military materiel from reaching Germans but also food.

Germany, wrote the United Press correspondent in Berlin, Carl Ackerman, looked “like a grocery store after a closing out sale.” While little outright starvation occurred, death from malnutrition is conservatively estimated at 300,000.

German submarine warfare also violated conventions.

If a U-boat was to announce it was about to sink a vessel, as called for by cruiser rules, it had to surface and thus became an easy target. This could be problematic even when confronting merchant vessels, as the British sometimes armed them. (The British also used flag ruses in which they put neutral country flags on armed merchant vessels.)

An additional concern on the part of the Germans was that passenger liners could be carrying munitions to support the Allies.

Also unprecedented was the systematic, wide-ranging use of propaganda in both its forms – the provision of information and the suppression of it.

Heavy-handed messaging from Berlin

The Germans restricted what their own citizens knew and assiduously aroused support not only among their citizens at home but also among German-Americans, whose influence might keep the United States out of the war. Most propaganda was in military hands, and accordingly had a martial heavy-handedness to it.

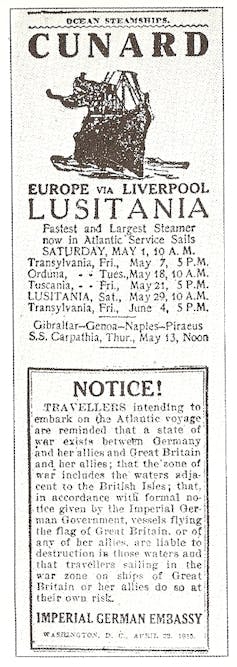

German warning. Robert Hung Picture Library

After the sinking of the Lusitania, German officials pointed out that the ship was carrying munitions and that they had placed ads in New York newspapers before the passenger liner sailed warning that ships under British flags were “liable to destruction.”

The Germans did not, however, elaborate on the impact of food shortages resulting from the blockade, a point that could have been used to elicit sympathy but would have revealed vulnerability.

Particularly damaging in terms of American public opinion was the German government’s defiant belligerence and even jubilation over the sinking of the ship, a sentiment picked up by its heavily controlled press.

The Lusitania was “drilled into the ground,” read a headline in the Bavarian Rosenheimer Anzeiger. In Cologne the Kölnische Volkszeitung celebrated “a success of moral significance.”

The chief German propagandist in the United States, Bernhard Dernburg, correctly observed that Americans could not visualize thousands of “German children starving by slow degrees as a result of the British blockade, but they can visualize the pitiful face of a little child drowning amidst the wreckage caused by a German torpedo.”

But he was subsequently so aggressively insensitive in his defense of the sinking that he made himself effectively persona non grata and had to return to Germany.

After the Lusitania sinking, the German Ambassador to the United States concluded, “The clarifying purposes of our propaganda in the United States essentially came to an end.”

Subterranean work by London

The British were far cleverer in their propaganda, which was carried out from a government building named Wellington House. This aspect of the story unfolds in documents in the British National Archives, the papers of the Times of London correspondent Arthur Willert at Yale and in other archives.

Despite Britain’s avowed democratic principles, Wellington House worked so quietly, even members of Parliament were unaware it existed.

In the United States this work was surreptitiously carried out by the novelist Sir Gilbert Parker, journalist Willert, and others who wooed opinion molders and planted stories in the American press.

A sign of their success was the lavish, tendentious press attention given to German spying in the United States and the absence of reporting on Britain’s underground activities.

“It should be noticed that no attack has been made upon us in any quarter of the United States,” Sir Gilbert Parker wrote in one of his periodic reports, “and that in the eyes of the American people the quiet and subterranean nature of our work has the appearance of purely private patriotism and enterprise.”

The British had an enormous advantage in communicating their point of view.

In the first hours of the war, they cut Germany’s transatlantic cable lines. This limited Germany’s capacity to send news to the United States and the ability of American correspondents in Berlin to send their reports home.

The British could be as heavy-handed as the German military. When William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers gave play to the German side of events, the British totally cut off their access to transatlantic cables. Then in a flurry of diplomatic activity, which produced hundreds of memoranda and cables, Foreign Office officials persuaded Commonwealth countries to do the same.

The British also cleverly magnified German public relations missteps.

Shortly after the sinking of the Lusitania, an artisan in Munich produced a medal depicting the event. This was a small, commercial endeavor involving fewer than five hundred medals, but the British made it appear yet another instance of the whole of Germany celebrating its brutality.

The British distributed pictures of the medal to newspapers and magazines both inside and outside Britain.

Commemorated in bronze. mrjohnsonssclasses, CC BY-SA

Wellington House reproduced 50,000 copies of the medal. After that, at the suggestion of the Foreign Office, department store magnate Harry Gordon Selfridge manufactured more, selling them around the world and donating the proceeds to the Red Cross.

German propaganda, exulted a British report, “sometimes defeats itself, for his methods are not seldom clumsy and crude…His communications are limited.”

American reactions

Some Americans, however, believed all sides shared blame for the prosecution of the war.

New York Times Lusitania Sinking.

Following the sinking of the Lusitania, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan wanted to protest the actions of both Germany and of Britain, whose blockade prevented “food from reaching non-combatant enemies.”

In a cabinet meeting, he erupted, “You people are not neutral. You are taking sides!” Bryan resigned when the administration focused its protests on Germany.

“American public opinion,” wrote journalist Mark Sullivan, in a post-war recounting of pervasive Allied and Central Power propaganda in the United States, “constituted a sector of the battle-front rather more important to capture than Mons or Verdun.”

Britain won that novel battle. In April 1917 President Wilson took the country into the war. After entering the war, the United States itself undertook wide-ranging, systematic propaganda for the first time in its history and has not stopped since.

The fight for public opinion is today a regular feature of diplomacy in war and in peace.

“Conventional wisdom holds that the state with the largest army prevails,” wrote Joseph Nye, Jr, a former State Department official and foreign policy scholar, “but in the information age, the state (or the non-state actor) with the best story may sometimes win.”

Editor’s note: this is an updated version of an article originally published to mark the 100th anniversary of the Lustinia’s sinking in May 2015.

![]()

—

John Maxwell Hamilton, Global Scholar at Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, DC and Hopkins P Breazeale Professor, Manship School of Mass Communications, Louisiana State University and Elisabeth Fondren, Doctoral Student in Media & Public Affairs, Louisiana State University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[Image Credit: Norman Wilkinson]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *