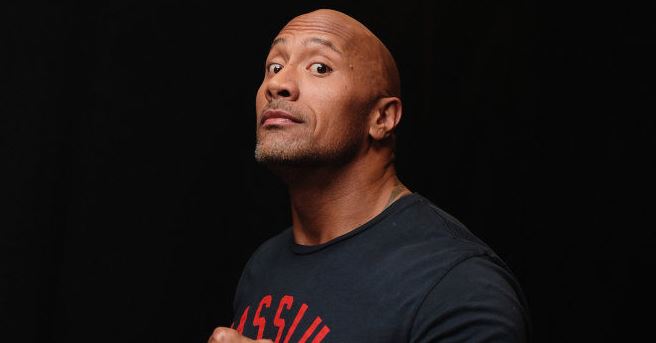

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson will play folk hero John Henry in an upcoming Netflix movie. Until the recent backlash, I was unaware that Johnson is only half black; his mother is Samoan.

Some think Johnson, who is among the highest-paid actors in the world, is not black enough to play a black man in the movies. One wrote, “John Henry was a very dark skin man & yes that matters.” Yet, John Henry is mythological. The skin shade of the “real” John Henry is uncertain; and like all folk tales, many aspects of the story “are subject to debate.”

Other critics say Dwayne Johnson hasn’t proclaimed his blackness enough to qualify as black. One tweet read, “The Rock is black when it’s profitable and racially ambiguous when it isn’t. We need a proud, strong, all-day black man to play John Henry.”

For Johnson, “the project held a special place in his heart because Henry was one of his ‘childhood heroes.’” Folk heroes have universal appeal; something in their character inspires us. Character, not a shade of skin, touches hearts and stirs us to action.

Ben Kingsley isn’t even part Jewish, and yet he masterfully played the part of the Jewish accountant, Itzhak Stern, in Schindler’s List. Kingsley’s role as an actor was to convey fear, adversity, decency, and hope. Universal emotions are not tied to ethnicity.

In the original Star Trek series, the episode “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” is a story of ethnic strife. The Enterprise was transporting back to the planet Cheron two warring alien humanoids, skin colored black on half their bodies and white on the other half.

One alien is Bele, a Cheron police commissioner, who has captured the political refugee, Lokai. Bele considers himself superior to Lokai. Why? Bele is white on the left side of his body, while Lokai is white on the right side.

Mutual hatred over this superficial difference had been going on for 50,000 years. In the final scene, Captain Kirk leaves them to return to their now-destroyed home planet, still going at it with each other.

Initially broadcast in 1969, the episode was a not too subtle allegory about race relations in the United States.

Race relations in America have improved since 1969, but those marching to the beat of identity politics threaten to take us back to terrible times.

In 1935, Nazi Germany passed the infamous Nuremberg Laws making legal the destruction of German Jewry. The preamble to the notorious 1935 Nuremberg Laws states:

“Moved by the understanding that purity of German blood is the essential condition for the continued existence of the German people, and inspired by the inflexible determination to ensure the existence of the German nation for all time, the Reichstag has unanimously adopted the following law.”

Jews were stripped of their German citizenship, making them aliens in their own land. They were forbidden to marry or have intercourse with other Germans.

Immediately the Nazis faced a problem: who was and who was not a Jew? Professor Thomas Childers in his book The Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, explains,

“Was it anyone with one Jewish grandparent, as the Civil Service law of 1933 had dictated? Two Jewish grandparents? Three? State officials, especially Economics Minister Schacht and Foreign Minister Constantin von Neurath, insisted on three grandparents; party radicals, led by Rudolf Hess, on only one. The army, concerned about manpower needs, also hoped for a more restrictive definition.”

Childers adds, “The status of racially mixed individuals—half Jews (two Jewish grandparents) or quarter Jews (one Jewish grandparent)—remained a source of conflict and confusion within the regime for years.”

Would those criticizing the selection of Dwayne Johnson to play John Henry be outraged by the idea that their mindset is the same as those who sought to determine who was Jewish in Nazi Germany? These critics would tell us they are motivated by good intentions: They want social justice for dark-skinned blacks. They might defend their racial evaluations claiming that, unlike the Nazis, it serves good purposes. Yet, underlying their criticisms of Johnson, it sounds like they believe there is an ideal black man that needs safeguarding from those of mixed blood.

Decades ago when my children were little, our family watched the delightful Disney movie, Tall Tale. In the film a young boy meets Pecos Bill, Paul Bunyan, John Henry, and Calamity Jane. Roger Aaron Brown played John Henry. I am now informed by critics of Johnson that Brown’s darker skin made him pure enough to play the part of John Henry.

I am certain that as we watched Tall Tale, no one in my family had even a passing thought of how dark John Henry’s skin was.

That’s the America I want to live in, not an America where identity politics reminds me of the Nuremberg Laws of Nazi Germany.

—

[Image Credit: Flickr-fmovies st, Public Domain]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *