More than a dozen people were recently arrested in El Cajon, California. Their crime? They were feeding the homeless.

“The arrests come in the wake of a newly enacted city ordinance banning people from feeding the homeless in public,” a local news station reported.

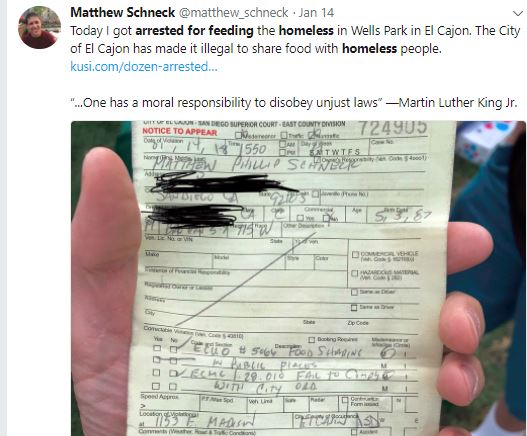

The group was aware of the ordinance, the report said, but defied the law in an act of civil disobedience on MLK Day. One man who was arrested proudly displayed his ticket on Twitter and referenced Rev. King in his tweet.

The story is interesting for a few reasons. First, the ordinance appears ham-fisted. Preventing people from assembling in a public place to offer charity to the destitute appears petty and wrongheaded, despite the city’s contention that the action was taken to protect the public health.

Second, there is a theatrical component to the story that is a tad troubling. Participants certainly have a right to feel frustration over the city’s ordinance, but is protesting it in this fashion the best way to help the hungry? I have my doubts.

The law might be foolish and unjust, and the act of civil disobedience might be an effective way to bring attention to the cause and pressure local politicians to change course. But there are alternatives to going to war (so to speak) with the city to feed the hungry.

If food could not be brought to the homeless, for example, perhaps the homeless could be brought to the food in a private location. This is less convenient of, course, but it could be used temporarily while a more permanent solution was explored.

Could the city and the protestors reach a reasonable agreement that allowed citizens to help the destitute through charity and goodwill? Maybe, maybe not. Governments sometimes are more interested in power than reason, as we’ve seen.

But immediately resorting to a political protest creates an adversarial relationship, which could make the ordinance even more difficult to repeal. Then the issue becomes a mere power struggle.

“Let us never forget that government is ourselves and not an alien power over us,” Franklin Roosevelt once observed. “The ultimate rulers of our democracy are not a President and senators and congressmen and government officials, but the voters of this country.”

I applaud the courage of those willing to take a stand for a cause in which they believe. But in his book After Virtue, philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre discussed the problems with such an approach.

[Protesting] is now almost entirely that negative phenomenon which characteristically occurs as a reaction to the alleged invasion of someone’s rights in the name of someone else’s utility. The self-assertive shrillness of protest arises because the facts of incommensurability ensure that protestors can never win an argument; the indignant self-righteousness arises because the facts of incommensurability ensure equally that the protestor can never lose an argument either. Hence the utterance of protest is characteristically addressed to those who already share the protestors’ premises. The effects of incommensurability ensure that the protestors rarely have anyone else to talk to but themselves. This is not to say that protest cannot be effective; it is to say that it cannot be rationally effective and that its dominant modes of expression give evidence of a certain perhaps unconscious awareness of this.”

But both government officials and those who protest the government would do well to remember FDR’s truth.

Government and the people are not adversaries; and our goal should be to create a government that responds to reason, not merely to power or theatrics.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *