The recent death of American poet John Ashbery sadly removed the last of his generation’s major poets. The current population of U.S. poets is now bereft of any truly significant figures — although there are many skillful writers of this hermetic yet important language art.

How long Ashbery’s work will last is not clear. Mostly alone among his contemporaries with the ability to convey complex “philosophical” insights and original imagery without excess academicism and gratuitous referential presumption, especially in his earlier work, Ashbery’s gift was immediately apparent. Although his later work became stylized, it always had wit and surprise.

Ashbery’s passing raises once again the question of why there are no “great” living American poets today. The answer to this is complicated by the fact that poetry, like most art forms in the U.S. culture, has been politicized and isolated by academic tastemakers and other self-styled literary umpires of what is not only “good” or “bad,” but also what is politically correct and “acceptable.”

In our post-World War II culture, the unseemly seeking of financial grants, prizes and critical notice, also moved our poetry into narrow regional and academic literary establishmentarian “controls” even as “beat poets” shook up literary orthodoxy (as each new generation of poets usually does).

The ”beat poetry” of the 1950s overturned literary conventions, but at the same time it adopted a distinct political direction which continues, with new issues, to the present time. Except for poets like Ashbery and a few others such as Frank O’Hara, the originality was often subsumed to political attitudes and causes.

In pre-World War II U.S. culture, there was also a political preoccupation, especially in the 1930s, in poetry; but unlike the leftist domination of the art today, the community of American (and European) poets was much divided between the far left and the far right.

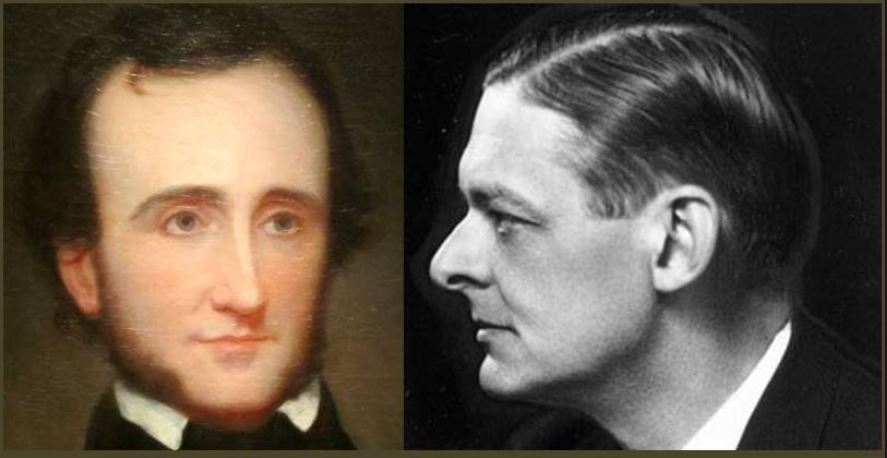

U.S. poets, such as Ezra Pound and (to a lesser degree) T.S. Eliot, openly espoused pro-Nazi or pro-fascist views. Pound particularly put these views into his poetry, and his reputation remains very diminished today (despite some academic attempts to rationalize his conduct).

Marxist U.S. poets in this period went through a political roller coaster as Stalinist Russia was first an enemy of Hitler, then briefly an ally of Hitler, then a U.S. ally, and finally a Cold War opponent.

Judgments about poetry and poets, as in every art form, are subjective. But fiction, theater and poetry are language arts particularly sensitive to political distortion. Since the academic and literary establishments today are quite overwhelmingly leaning left, there is, in my opinion, a powerful deterrence to verbal originality, especially in poetry (which requires taking language to new dimensions and places).

It’s not that poets today are any less talented or gifted than our many great poets of the past. But language has been clearly and understandably altered by technological change, generational perceptions, and political “sand traps.”

Poets such as Tomas Transtromer in Swedish and John Ashbery in English were so original they could overcome contemporary obstacles. In the 19th century, and just after World War I, there were also obstacles, but perhaps not as extreme as those in our own time.

Poetry today has a small and limited audience, but the art of poetry is too vitally linked to the health and quality of language itself not to produce (hopefully soon) new and original voices that tear down political walls.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *