One Saturday afternoon a number of years ago, my family received a call from my uncle, an amateur beekeeper. He had just harvested his hives and wondered if we were interested in helping with the extracting process.

We took him up on the offer and spent the rest of the evening learning how honey makes its way from the frames of the hive to the jar on the table. Needless to say, it was probably one of the most memorable impromptu learning experiences I’ve ever had.

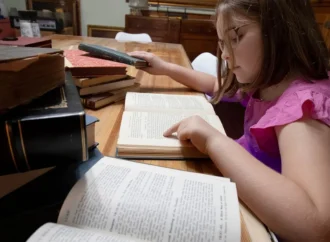

Unique, hands-on learning experiences such as mine don’t happen very often in today’s schools. But that may be changing on various school campuses around Great Britain.

According to The Guardian, the alleged honeybee crisis has spurred various beekeepers to take their craft to elementary schools. To their surprise, such a move has been better received and provided more learning opportunities than may have been anticipated:

“Dr Julia Hoggard has kept bees for 30 years and runs a 20-acre, bee-orientated nature reserve in Cumbria. For the past year, she has been working with a local primary school, helping the students to create their own hives.

…

‘The advantage of having them in schools is that they are neat little communities; you can look at every single aspect of what is going on and link it into the curriculum at all key stages.’

There are the obvious subject links with biology and environmental science – studying mini beasts, pollination and sustainability, for example – but a hive can also be used to explore elements of history, art, maths and music, as well as providing opportunities for developing practical skills: using woodwork lessons to construct the hive, or making dishes using honey in food technology.”

According to those who have tried it, children revel in such lessons, enjoying both the sensory experiences and the excitement and danger that working with bees can bring.

In recent years, classrooms have placed a decided emphasis on getting through the latest textbook, worksheet, or exam. As a result, they have little conception as to how multiple academic subjects and knowledge fit together to form a cohesive whole. Furthermore, such an emphasis eliminates opportunities for many hands-on, real-life learning experiences, including building, cooking, or working in nature.

British educator Charlotte Mason once said:

“A great deal has been said lately about the danger of overpressure, of requiring too much mental work from a child of tender years. The danger exists; but lies, not in giving the child too much, but in giving him the wrong thing to do, the sort of work for which the present state of his mental development does not fit him. … But give the child work that Nature intended for him, and the quantity he can get through with ease is practically unlimited. Whoever saw a child tired of seeing, of examining in his own way, unfamiliar things? This is the sort of mental nourishment for which he has an unbounded appetite, because it is that food of the mind on which, for the present, he is meant to grow.”

Is it possible that in our quest for a well-rounded, knowledge-intense school experience, we have diminished our children’s desire for learning? Would we see that desire return if we returned those types of hands-on, natural learning experiences to the school curriculum?

—

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *