We would all like to live in a world without hate. Indeed, most of us would like to live in a life without hate.

But I would like to make another, and more modest, proposal regarding “Hate-“. By this, I mean the use of the word “hate” to add extra zing to some public policy debates. You may not have noticed, but that old lower case noun that has been forcibly converted into a capitalized and sometimes-hyphenated adjective.

The use of “Hate-” spread when polemicists needed a hard-working word that meant much more than “bad” and instead captures the special concerns some people have about some kinds of bad behavior. Assaults and robberies were bad, sure, but if certain especially bad worldviews swirled within the loathsome mind of the assailant, each punch the attacker landed was somehow worth extra outrage and enhanced penalties. Thus “Hate-crime” entered the lexicon.

If you hurt someone at random: bad. If you hurt someone because of who you thought they were: worse.

As a result we are treated to reports of awful behavior and instructed to be particularly aghast if it is a “Hate-” crime. Conversely, bad behavior seems, sometimes, “only” bad: “Billy bashed a lady’s head in last night. At least it wasn’t a “hate” crime.” Many sensible people are growing tired of the term because most crime, or at least most violent crime, is hate crime, with no associated capital letter or special gasp.

The adjective “Hate-” performs no analytic function, nor does it reflect the application of any universal principles or guidelines. Instead, it is a purely an ad hoc normative judgment. The term merely predicts which crimes will be pursued and punished most vigorously. So if Billy bashes the lady’s head for no reason, that is bad. Bad Billy. But if he does it for the wrong reason, Bad Bad Billy.

It is time to take identity politics out of murders, rapes and assaults. I promise you that in each case, there is plenty of hate there to explain it. Don’t get me wrong, I am in favor of tough penalties for all violent crimes–just don’t let some criminals off easy because they did not check certain boxes when they violated the rights of other people.

Likewise, “Hate-speech” must also be discarded as a sinister constraint on the marketplace of ideas. Promoters of one orthodoxy or another, and countless “isms” and “ists”, like to invoke “Hate-” to signal that some particular parcel of words is so bad that our normal solicitude for free speech does not apply.

“The First Amendment does not protect Hate-speech” really means “I do not like that the First Amendment is so recklessly broad that it includes things I do not like.”

News flash: the First Amendment does protect hateful speech and it is supposed to. From the Colonial Revolution’s “Down with the King” to current times, the American experiment has relied on free speech and all kinds of rhetoric to populate the testing ground of ideas. To one person, some speech is “Hate-” speech and to another it is speaking truth to power or protecting important principles.

As with “-crime”, to use “Hate-“ before “speech” performs no analytic function. It does not look deeper into the purpose or context of the words or the conduct of the speaker. Rather, that little prefix merely signals what its user thinks should be done with the other person’s right to speak and be heard. There is an implicit mechanical device in the term “Hate-speech. It has two parts: (1) “if it is Hate-speech, it can be restricted” and, no surprise here, (2) “I decide what hate-speech is.

So let’s do away with “Hate-“with a hyphen. Maybe that will help us better battle the hate which has no hyphen.

—

Peter W. Laberee is a middle-aged lawyer who lives in New Jersey.

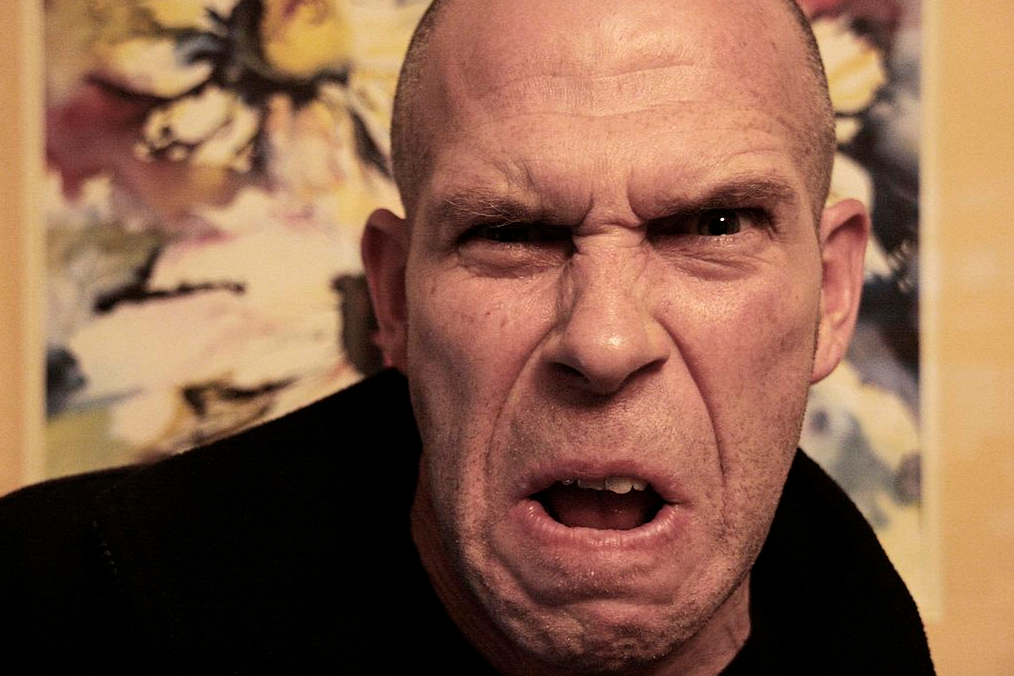

[Image Credit: Cruxnow]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *