One of the funniest, but also most painful-to-watch, parts of Planes, Trains, and Automobiles is in the Wichita hotel, when Steve Martin’s character has reached the boiling point with John Candy’s character, and finally unloads on him in a classic rant.

At the close of the rant, he says the following:

“And by the way, when you’re telling these little stories, here’s a good idea: Have a point! It makes it so much more interesting for the listener!”

The same advice, I feel, is applicable to us when we read a story, or any book for that matter: Have a point!

Granted, the bigger problem in America is that a large percentage of the population doesn’t read books at all.

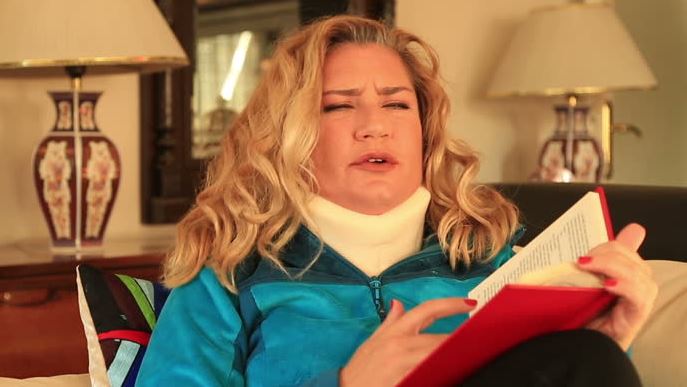

But for those of us who do read, I fear a lot of time is wasted trying to plow through books without a concrete understanding of how they will improve our knowledge. They’re the ones we attempt to read purely because we think we should, or because other people have read them, or because they’re recommended to us, or because we think they’ll make us smart (or at least feel smart).

It’s usually painful trying to get through them. Picking them up feels like a chore, and after weeks or months of sporadic engagement with them, we may finally wave the white flag and move on. And even if we did somehow manage to get all the way through them, their information usually passes through us like a sieve, because we weren’t really committed to them in the first place.

Because life is short, we should try to avoid such reading digressions as much as possible. To do that, I think a good rule of thumb is R.G. Collingwood’s logic of “question and answer”.

For those who haven’t heard of him, Collingwood (1889-1943) was a renowned philosopher of history. His book The Idea of History was listed on the National Review’s list of the Best 100 Nonfiction Books of the [20th] Century.

In the celebrated Chapter 4 of his Autobiography, Collingwood explains the logic of “question and answer” that guided his own work:

“I began by observing that you cannot find out what a man means by simply studying his spoken or written statements, even though he has spoken or written with perfect command of language and perfectly truthful intention. In order to find out his meaning you must also know what the question was (a question in his own mind, and presumed by him to be in yours) to which the thing he has said or written was meant as an answer.”

Collingwood’s point seems simple, but sometimes the simple is what we most need reminding of.

To be purposeful in our reading, and to better avoid wasting time, we need to have a good self-awareness about what questions are motivating us in our search for knowledge and truth. Our reading of books should be attempts to find answers to those questions, just as the writing of them were the authors’ attempts to do the same.

—

Dear Readers,

Big Tech is suppressing our reach, refusing to let us advertise and squelching our ability to serve up a steady diet of truth and ideas. Help us fight back by becoming a member for just $5 a month and then join the discussion on Parler @CharlemagneInstitute!

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *