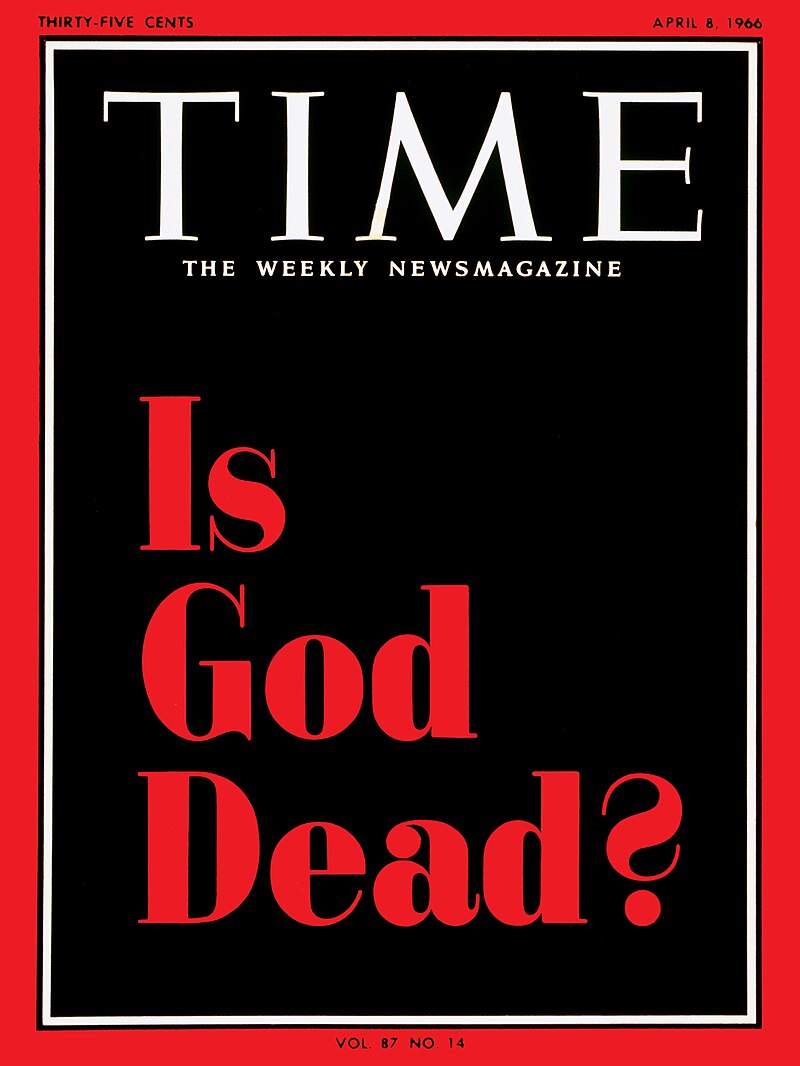

Last week marked the 50th anniversary of one of the most famous magazine covers ever.

In The Gay Science (1882), Friedrich Nietzsche’s character of the madman had proclaimed, “God is dead.” The Time cover for April 8, 1966, turned this proclamation into a provocative question for a world where religious practice was waning:

But, though most people have heard of Nietzsche’s “God is dead” claim, there are few who understand its intended meaning.

To get at this meaning, it’s first important to read the phrase in the context of section 125 of The Gay Science:

“God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How can we console ourselves, the murderers of all murderers! The holiest and the mightiest thing the world has ever possessed has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood from us? With what water could we clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what holy games will we have to invent for ourselves? Is the magnitude of this deed not too great for us? Do we not ourselves have to become gods merely to appear worthy of it? There was never a greater deed – and whoever is horn after us will on account of this deed belong to a higher history than all history up to now!’ Here the madman fell silent and looked again at his listeners; they too were silent and looked at him disconcertedly. Finally he threw his lantern on the ground so that it broke into pieces and went out. ‘I come too early’, he then said; ‘my time is not yet. This tremendous event is still on its way, wandering; it has not yet reached the ears of men. Lightning and thunder need time; the light of the stars needs time; deeds need time, even after they are done, in order to be seen and heard. This deed is still more remote to them than the remotest stars – and yet they have done it themselves!’”

As an atheist, Nietzsche did not believe in God. Thus, he did not believe that God had once existed but was now “dead.”—Pretty obvious.

What Nietzsche was referring to by “God is dead” is the general decline of Christianity that was taking place (and is still taking place, depending on who you ask) in the Western world. He explains “God is dead” later on in The Gay Science: “the belief in the Christian God has become unbelievable.”—Again, pretty obvious to most people.

But here’s where things get tricky. Nietzsche’s exasperation, expressed in the form of the madman, was directed at people’s ignorance at the loss of a ground of morality—indeed, as he says, the “collapse” of “our entire European morality.”

With the “death” of the Christian God, Nietzsche believed that the Western world’s foundation for morality had been destroyed. It’s just that the people in the West hadn’t realized it, yet. The madman who tried to make them realize it had “come too early.”

And perhaps people today still don’t realize it; perhaps it’s still too early. Many still throw around the old moral injunctions in secular society, and for the sake of the secular public square, often attempt to justify them with some other foundation—e.g., what’s “natural,” what’s “useful,” what’s “practical,” what leads to “prosperity.” (I often wonder if this is the fatal weakness of conservative politicians in America: they attempt to defend Christian values, but somehow try to justify them based on alternative foundations for the sake of making them more “palatable.”)

For instance, some try to encourage stable families statistics show that’s the surest pathway to success in life for kids. Others oppose gay marriage on the basis that history has shown that reserving marriage for a man and a woman is best for the health of a society. And others say that we should impose regulations on businesses for the apparently self-evident reason that we should protect the environment for future generations.

But telling people that they should do something because it’s “useful” or “best for society,” or avoid something because it may lead to “poverty” or “create chaos,” does not necessarily imply “right” or “wrong.” These reasons do not contain within them an obligation for people to act a certain way based on how things actually are in reality.

What Nietzsche said, and probably rightly so, was that moral injunctions today and their substitute foundations are just the “will to power” in disguise—that of an individual, a group, a race, or a government. The old injunctions, previously tied to Christian metaphysics, are now just “useful” as a means to control people for selfish reasons, whether it be to achieve personal fulfillment, or maintain power, or bring about one’s utopian vision.

“God is dead, and we have killed him.” When it comes to justifying morality, can anything legitimately take his place?

1 Comment

John E Reuter, Esq. (Ret.)

July 19, 2022, 9:59 pmNope, he meant it quite literally. God is indeed dead and let’s mark it’s burial as beginning of the end in America as the 1960s. Modernity has no God, no gods, nothing but Relativism and Amorality, Death and Destruction, Global Existential Nihilism, Humanity as Generational Feuilletons.

REPLY