It’s not hard to find or be exposed to thoughts and opinions that reflect the deeper intellectual chaos of our times. If one senses the fog created when rational thought is taken to absurd extremes, the passage below from G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy will probably resonate. If not, then the passage will probably make little sense and may even seem to be itself absurd.

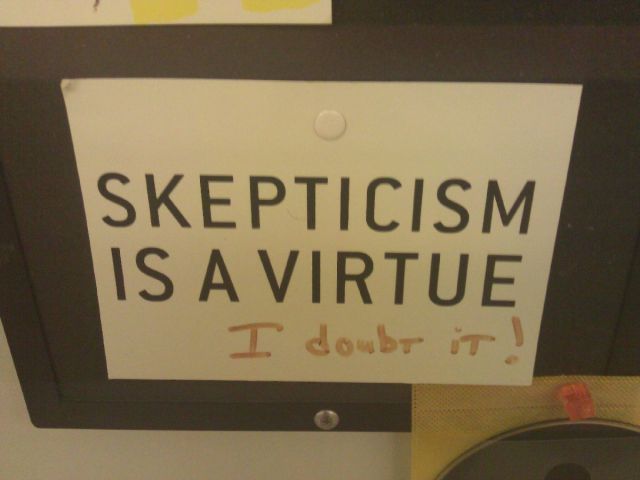

“To sum up our contention so far, we may say that the most characteristic current philosophies have not only a touch of mania, but a touch of suicidal mania. The mere questioner has knocked his head against the limits of human thought; and cracked it. This is what makes so futile the warnings of the orthodox and the boasts of the advanced about the dangerous boyhood of free thought. What we are looking at is not the boyhood of free thought; it is the old age and ultimate dissolution of free thought. It is vain for bishops and pious bigwigs to discuss what dreadful things will happen if wild skepticism runs its course. It has run its course. It is vain for eloquent atheists to talk of the great truths that will be revealed if once we see free thought begin. We have seen it end. It has no more questions to ask; it has questioned itself. You cannot call up any wilder vision than a city in which men ask themselves if they have any selves. You cannot fancy a more skeptical world than that in which men doubt if there is a world.”

Most of the folks reading Intellectual Takeout are between 18- and 40-years-old. The majority are towards the younger side of the spectrum. Most of the authors who write for Intellectual Takeout are also in that age range.

Why do I mention that? Because for the younger members of our society, the world of ideas is generally new. We are still discovering the writings of thinkers, both great and terrible. We are only beginning to realize that the arguments and ideas we’re presented with by the living are usually just the regurgitation of what has already been said in the past. Furthermore, because of the spirit of our age, with its demand for progress and newness, we often don’t realize just how much the ideologies and revolutions of the past, even ones from many centuries ago – even thousands of years ago, still shape us today. The spirit of the age also makes it hard to discern what is worthy of study and pursuit compared to what is not.

When we look at Chesterton’s snippet above, we must understand that he is writing from the long-view. While the intellectual currents shaping thinking today are new to us, they are actually quite old – and running on fumes.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *