If you ever read the Betsy-Tacy series by Maud Hart Lovelace as a kid, you probably know that Betsy and her friends were big fans of producing home-grown entertainment programs.

And the entertainment perpetually ran along the same lines: Betsy and Tacy performed the Cat Duet, little Tib did the Baby Dance, talented Julia played the piano or sang, and poor, stage-fright Katie always recited Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

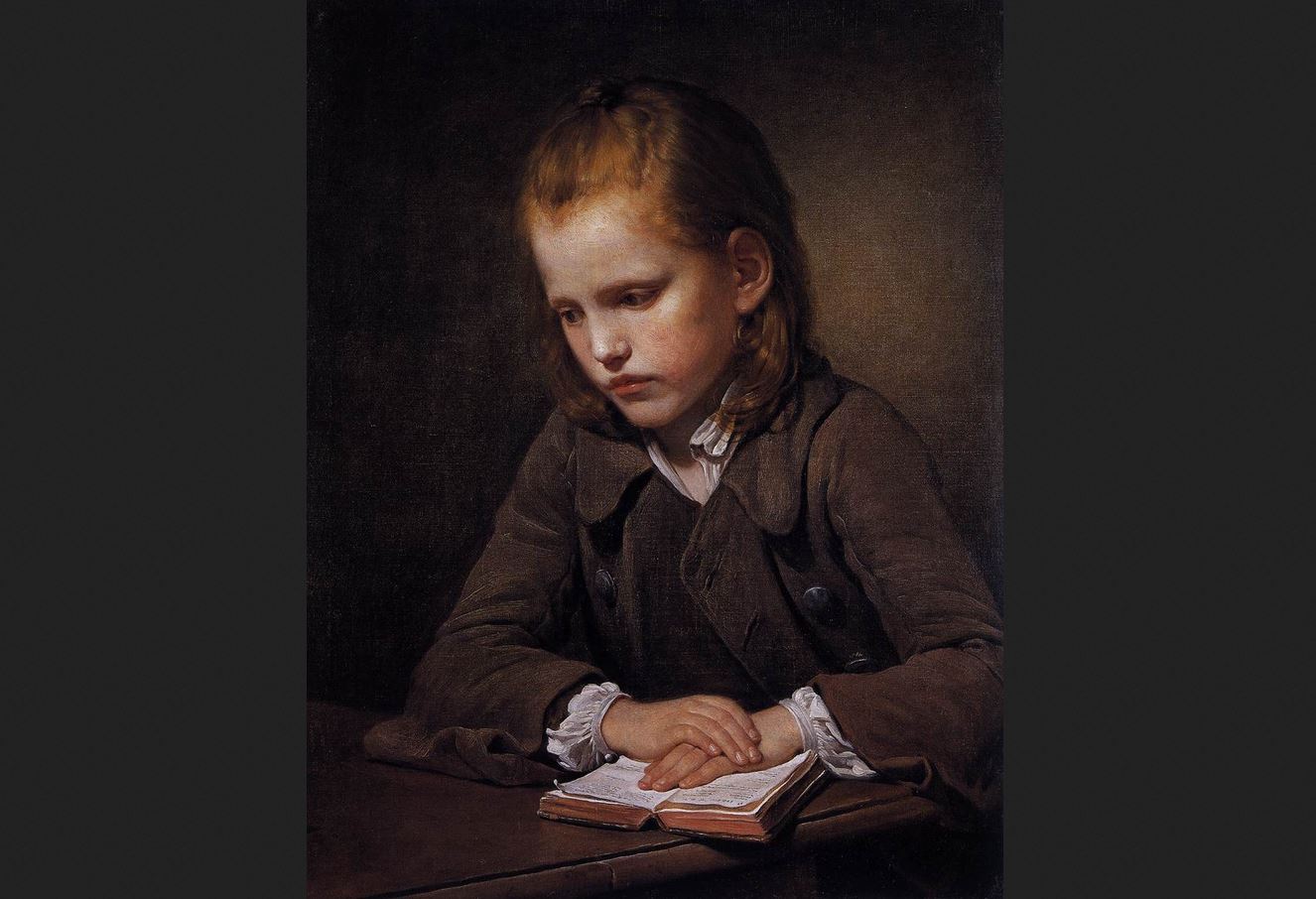

It was Katie’s nervous, regular recital of The Gettysburg Address that made me stop and think. Admittedly, Katie did not possess the stage talent and performing nature of the other children in the book. Yet because she had been required in school to commit The Gettysburg Address to memory, she had a ready performance at her fingertips, and was likely able to draw on and muse over its words well into her adulthood.

Memorization of poems and classic speeches like The Gettysburg Address has admittedly fallen out of favor today. Many schools perceive memorization as an unengaging, useless task, preferring instead to instill their students with critical thinking skills.

But as Dr. William Klemm implies in Psychology Today, memorization can actually build critical thinking skills, particularly as the practice exercises the mind and provides ready information from which students can readily draw. Furthermore, memorization can also help students focus, a quality which Klemm notes is “lacking in many youngsters,” a fact particularly “obvious in the growing number of kids diagnosed with ADHD.”

Given these benefits, should schools be more accepting of memorization and once again expect students to commit items like The Gettysburg Address to memory?

1 Comment

Daniel A. Hennessy

February 11, 2024, 12:44 pmYES! My jr.high and high school students participated in a modified classroom version of "Poetry Out Loud," a national program of memorizing and reciting poetry. I watched the meekest and mildest of my students grow in character through the process of first reading and writing about their poem, then memorizing first one-half-, then completely, three full poems per school year, choosing one for recitation at the school assembly in May. They get to choose their own from a database of 600 poems; the search itself exposes them to more poetry than some people experience in a lifetime. Powerful, and positively nerve-wracking, fear-confronting stuff. A recipe for inner growth of character. You could see the power running through them…One of the deepest, most inwardly strengthening programs I'd ever run as a teacher. The process of choosing, reading, understanding, memorizing, then reciting poetry gave them a powerful sense of ownership. They 'owned' their poems and you could tell.

REPLY