When I hear the phrase “book ban,” the image that comes to mind is something straight out of “Fahrenheit 451” – books torn from private residences, doused in kerosene, and thrown onto a blazing funeral pyre of intellectual tradition, removing all certainty that such works ever existed.

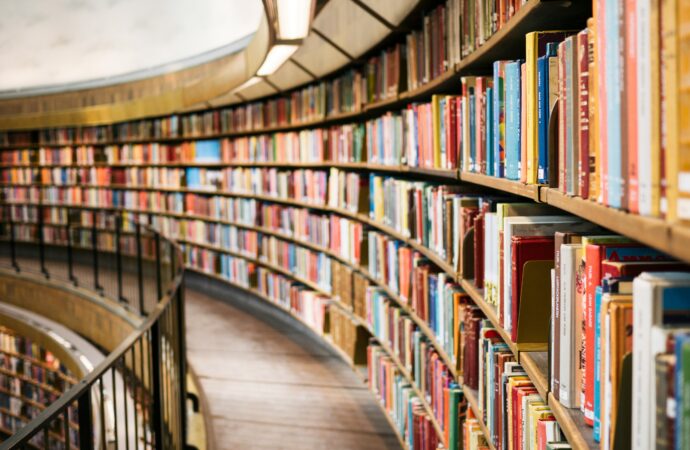

Yet when American media uses the phrase “book ban,” it usually means “removed from the shelves of a public school library.” The book may be gone from those shelves, but it’s still in print, available at bookstores, and accessible online.

Since autumn of 2021, PEN America reports 23,000 book bans in American public schools and 10,000 unique challenged titles. Most of these books are challenged for obscenity or discussion of LGBTQ+ and racial themes, topics that are often too mature for schoolchildren. Yet every removal of a book from school shelves is met with flaming accusations of censorship.

Rarely does anyone argue that every type of media is appropriate for all age groups. Yet we sometimes forget that adults are gatekeepers for what children see. Beyond the oft-disputed topics of sexuality and race, I would argue that discussions of mental health disorders, abuse, and war should be regarded with an equally critical eye before being made available to children. They may be excellent books, but I wouldn’t hand off Anthony Burgess’ “A Clockwork Orange” or Elie Wiesel’s “Night” to a 10-year-old.

The most invoked defense for book bans in schools is “parental rights.” Many parents are uncomfortable with their children being exposed to sensitive topics without their consent, and rightfully so. Parents ought to be informed of everything that is taught in their child’s school.

Indeed, parental authority should trump school librarians’ or educators’ opinions every time. Parents must be kept continually aware of the books that their children read in school, having the right to opt their children out of any required reading they deem inappropriate.

But what about the parents who are comfortable with their children encountering controversial topics at school? Or the parents who want their children to read books about racism or LGBTQ+ characters? Do their rights matter just as much as those of parents who don’t want their children exposed to such content?

Like it or not, parental authority belongs to all. Likewise, the freedom of the press guaranteed by the First Amendment applies to both sides of the political aisle. It is not selective. Thus, if a conservative parent can prohibit his child from reading an assigned book like “Looking for Alaska,” which contains sexually explicit content, a Muslim parent may also decline to let his child read an assigned book preaching Christianity.

Even so, reforms are needed. So how can parents who wish to monitor their children’s access to various literature ensure that their parental rights and decisions are not trumped by the curated choices of school librarians and educators?

First, parents should be given access to their child’s entire school library catalog at the beginning of each academic year. That way, parents on either side of the political or religious aisle can have the option to select books that they do not wish their child to check out.

Second, parents should receive an email from the school each time their child checks out a book from the school library that includes titles, authors, and a link to a book description so they can supervise their child’s reading.

Third, frequently challenged books – including “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” “The Kite Runner,” and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” – should be included in a “restricted section” of the library, making them less accessible to students who might unknowingly begin reading a book that is far too mature for them. Parents should be able to opt their child in or out of access to this section of the library.

These propositions defer to parental authority, rather than allowing school authorities to make decisions on behalf of parents without their consent.

Interestingly, 72% of attempts to remove books from state-run entities are pioneered not by parents, but government entities such as board members and elected officials. Parents only make up 16% of this statistic. Thus it seems the removal of books from schools without parental pressure may be a gross overstep of the government, which intends to make parenting choices on behalf of its citizens.

If you support the power of parental authority, you can’t be selective about whose parental authority is worth more. When it comes to what their children can read, parents should always get the last word.

Image credit: Unsplash

1 comment

1 Comment

JKH

December 10, 2025, 10:06 amMany people are not aware that there are groups that gather boxes of books, some age appropriate or inocus but there is also a sprinkling in of very objectional books and ship them to schools during the summer. I became aware of this when my 6th grader brought home a book by Philip Roth depicting sadistic sex ending in murder. When I went to the school librarian, she said that she receives these books and there are so many she doesn't have time to research them so she puts them out as they come with catalog numbers. Not an excuse but she said it happens every summer, large boxes of books come unordered from organizations she had not heard of before. She said I was the first parent to notice anything wrong. Then she resigned.

REPLYIn my high school library, in 1971, The Godfather was on the shelf, by 1975 the book fell open to page 28, I doubt anyone read any other page in the book.