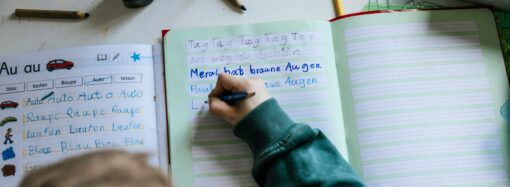

Several times a year I require my students to memorize a poem. Sometimes I choose for them (say, “Death Be Not Proud,” by John Donne). Sometimes I hand them an anthology and let them choose. I don’t explain rhyme scheme or poetic devices. I only ask that the students know the meaning of every word in the poem, looking them up in the dictionary if they don’t.

At the beginning of the second semester, they receive their biggest poetry assignment of the year. I give them a list of long poems, none less than 40 lines, giving them eight weeks or so to choose one and memorize it. Their options range from Thomas Gray (1716-1771) to Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), with plenty of 19th-century choices (Keats, Coleridge, Poe). Inside those parameters, they’re free to follow their whims.

What I don’t tell the students is that many of these poems are considered un-cool, outdated, or just plain hard by literary critics, English professors, and the public at large. All the students know is that these poems happen to be in a book on the shelf in my classroom.

There’s freedom in their ignorance. No student has ever picked a poem because it’s “famous” or “important.” The many students who memorize Felicia Hemens’ “Casabianca” don’t know it’s been out of fashion for 75 years. They just like the way it sounds. As epic war poems go, George Croly’s “The Death of Leonidas” is a bit of a clunker, but it still stirs adolescent blood. Sometimes the students pick ones that “look easy,” but for the most part, when I ask them why they were drawn to one poem over all the others, they respond, “I just liked it.”

“Genuine poetry can communicate before it’s understood,” T. S. Eliot said. It’s true. Difficult language is easier to accept in poetry than in prose. Many of my students choose poems without knowing what they mean and consequently spend a lot of time with a dictionary. One pored over the second stanza of “Loveliest of Trees, the Cherry Now,” by A. E. Housman, until he figured out the convoluted math and his eyes lit up with new appreciation. One time, I read Tennyson’s “Ulysses” to the class, and they applauded. It wasn’t my reading they were applauding, nor the sentiments expressed in the poem. It was the sheer sound of the words that moved them to applaud.

You may think of poetry with slight distaste, perhaps even a little embarrassment, as something you know you’re supposed to appreciate but can’t. Dana Gioia, former Poet Laureate of the United States and the author of “Poetry as Enchantment,” has said that the unpopularity of poetry is probably due to its being “too well taught.” Who could blame you for disliking something that takes a week of lectures on rhyme, meter, lyric forms, poetic devices, literary trends, and English grammar to appreciate? It’s like taking a Science of Cooking class before eating a hamburger. Instead, Gioia urges a return to the enchanting power of poetry. Read poems out loud, he says. Better yet, recite them from memory. Serve them to an engaged audience. That’s what poems are for.

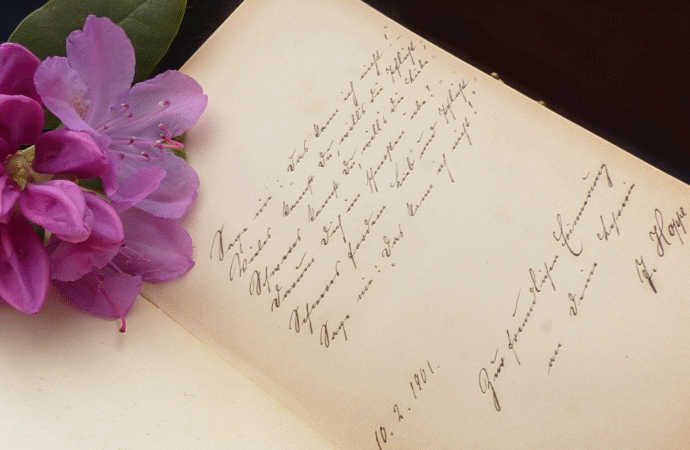

Poetry has always been an elevated form of language, but until recently, it had a practical side as well. The simple fact is that it’s easier to memorize poetry than prose. The meter, the rhyme, and the vivid language all make the words come more quickly to mind. Historically, this quirk meant that poetry could be used to record things that would otherwise be lost to time – stories, legends, history, wisdom, worship. Nowadays, poems are more often used to record impressions of life, moments of beauty, insights into the self, small things worth noting. Robert Frost once said that poetry is “a way of remembering what it would impoverish us to forget.” My students don’t know this, but in memorizing poetry, they are sandbagging themselves against the natural force of time, which could cause them to forget the things that are really important.

Let’s say I’ve convinced you. You resolve to memorize a poem. Where should you start?

Start with the least pretentious poetry collection you can find, something like Robert Louis Stevenson’s “A Child’s Garden of Verses.” No poem is too small or too humble. Based on Gioia’s recommendation, I picked up a copy of Garrison Keillor’s anthology “Good Poems,” which has, so far, lived up to its unpretentious name.

At the end of the day, the right poem to memorize is the one that, when someone asks why you were drawn to it, prompts you to honestly respond, “I just liked it.”

—

The republication of this article is made possible by The Fred & Rheta Skelton Center for Cultural Renewal.

Image Credit: Pxhere

22 comments

22 Comments

OllieICole

July 1, 2025, 2:32 amI get paid over $220 per hour working from home with 2 kids at home. I never thought I would be able to do it but my best friend earns over 25k a month doing this and she convinced me to try. it was all true and has totally changed my life… This is what I do, check it out by Visiting Following Site……HERE====)> https://Www.JoinSalary.Com

REPLYMalani Woolf@ OllieICole

July 1, 2025, 2:07 pmYou could easily earn 💵$500 from this even if you have never worked online.

Kindly check it out on the relevant website. I said this first. Assess your abilities, interests, and pastimes first. Find out what you have a passion for or abilities that you can sell. ……

Here is I started.…………>> https://Www.EarnApp1.Com

REPLYMalani Woolf@Malani Woolf

July 1, 2025, 2:08 pmGoogle pay 500$ per hour my last pay check was $19840 working 10 hours a week online. My younger brother friend has been averaging 22k for months now and he works about 24 hours a week. I cant believe how easy it was once I tried it out.

Just join This Website……… http://Www.HighProfit1.Com

REPLYFeatherjourney@Malani Woolf

July 2, 2025, 5:28 amEverybody can earn 220$/h + daily 1K… You can earn from 6000-12000 a month or even more if you work as a part time Work…It’s easy, just follow instructions on this page, read it carefully from start to finish… It’s a flexible job but a good eaning opportunity..go to this site home tab for more detail thank you…….

REPLY.

Reading This Article:———- https://Www.Cash43.Com

EMMA@Malani Woolf

July 3, 2025, 12:13 pmI’m making over $13k a month working part time. I kept hearing other people tell me how much money they can make online so I decided to look into it. Well, it was all true and has totally changed my life. This is where I started

REPLY.

Reading This Article:—– http://Www.Payathome9.Com

LawrenceMJones@ OllieICole

July 3, 2025, 6:44 amGoogle pay 500$ per hour my last pay check was $19840 working 10 hours a week online. My younger brother friend has been averaging 22k for months now and he works about 24 hours a week.

REPLYJust Open This Website…….. http://www.get.money63.com

OllieICole

July 1, 2025, 2:33 amI get paid over $220 per hour working from home with 2 kids at home. I never thought I would be able to do it but my best friend earns over 25k a month doing this and she convinced me to try. it was all true and has totally changed my life… This is what I do, check it out by Visiting Following Site……HERE====)> https://Www.JoinSalary.Com

REPLYJeffrey C. Williams

July 1, 2025, 5:12 amI earn $85 hourly for working online from home. I never thought that it’s possible but my best friend is making $10000 every month working this job and she told me about it.

Check it out by visiting following link >> http://www.pay.works6.com

REPLYLloydNRider

July 1, 2025, 5:20 amI getting Paid upto $18953 this week, Working Online at Home. I’m full time Student. I Surprised when my sister's told me about her check that was $97k. It’s really simple to do. Everyone can get this job.Go to home media tab for more details.

REPLYSee…………………… Www.Works6.Com

Kelvin B. Bunce

July 1, 2025, 6:22 amI am profiting (900$ to 1000$/hr ) online from my workstation. A month ago I GOT check of about 30k$, this online work is basic and direct, don’t need to go OFFICE, Its home online activity. By then this work opportunity is begin your work….★★

Copy Here And Open It→→→→ http://www.earn54.com

REPLY