He was one of those people who fit Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ definition of a great thinker with great impact on the world. The hallmark of such a thinker is not personal notoriety but the fact that ‘a hundred years after he is dead and forgotten, men who never heard of him will be moving to the measure of his thought.’ Hayek’s thought, though little known to the general public even within his own lifetime (the Nobel Prize committee being an exception, however), has inspired numerous other scholars, writers, activists, and organizations around the world.

Thomas Sowell is right: Friedreich Hayek was a great thinker, and his ideas have made a great impact on the world. Yet even though he forever changed economic and political thought, many people have never heard Hayek’s name. Here’s why everyone needs to read this essential thinker.

When most people think of economics, they think of a confusing jumble of numbers and equations. While that may be true of some neoclassical economists, it doesn’t apply to Hayek’s work. His seminal essay, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” continues to be taught in economics classes around the world, but it doesn’t contain a single mathematical formula.

Instead of falling back on technical jargon, Hayek puts human knowledge at the center of his studies. As he argues, many important forms of knowledge aren’t scientific in nature. Instead, they’re tied to the specifics of time and place. For example, a farmer might rely upon scientific principles to fertilize and care for his fields. However, he will also draw on his experience with his specific soil, crops, and animals as he goes about his work. Much of that knowledge would be impossible to communicate to someone else.

In fact, Hayek points out that many forms of knowledge can’t be communicated. You can tell a person what they need to do to build a chair—does that mean they can actually build it? Try it at home.

Hayek draws some important policy conclusions from this foundational observation. As he argues, people who want a planned economy think that experts should be control businesses. But if you can’t effectively gather the knowledge that is needed to run a profitable business, then the planners won’t be basing their decisions on good information. Instead, they’ll be taking wild guesses as to what businesses should do.

A similar concern with knowledge animates Hayek’s most well-known book, The Road to Serfdom. In it, he shows that a great deal of policy questions can’t be resolved objectively. Instead, they depend on value judgments. And since there is no scientific way to assess competing values, politicians inevitably elevate the preferences of some citizens above others. This can create serious conflicts within a society.

It’s for this reason that Hayek advocated political restraint. Rather than use the government to achieve some vision of utopia, politicians should stick to policies on which there is widespread agreement—the common denominators of life, liberty, and property. Whenever politicians wander beyond this minimum, they invite political crisis.

Yet Hayek didn’t confine his arguments to politics and economics. He also wrote a remarkable book, The Sensory Order, that has come to be recognized as a foundational text in cognitive science. In many ways, Hayek’s argument in this text is decades ahead of its time—just as his work in the social sciences proved to be prophetic.

When Hayek set out to write The Sensory Order, people knew that the brain and the mind were deeply connected, but they had no idea how. All they knew was that if you stimulated (or injured) some part of the brain, you would affect the mind somehow. Hayek’s argument is the first to show how physical events in the brain can cause mental events in the mind. It remained the most advanced contribution to the field of cognitive science for over 20 years after it was written—no small feat for an economist!

So the next time you look for a book to read, consider Hayek. You’re likely to find that many people are borrowing from his ideas. Why not go straight to the source?

—

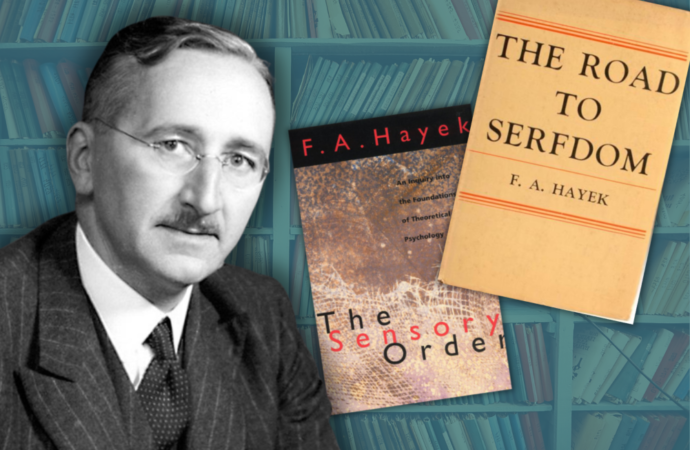

Image credits: “Friedrich Hayek Portrait” (image edited) by the Mises Institute on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0; Goodreads (The Sensory Order); public domain (The Road to Serfdom).

1 comment

1 Comment

Swissarge

September 4, 2024, 8:50 amIntellectuals explain things intellectually. The masses are a far cry from intellectual.

Politicians know this, this is why successful politicians, know the one rule that always work'

Tax the rich, let them pay their "fair" share. Simple. but effective

REPLY