In August 1989, Poland’s parliament did the unthinkable. The Soviet satellite state elected an anti-communist as its new prime minister.

The world waited with bated breath to see what would happen next. And then it happened: nothing.

When no Soviet tanks deployed to Poland to crush the rebels, political movements in other nations – first Hungary, followed by East Germany, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Romania – soon followed in what became known as the Revolutions of 1989.

The collapse of Communism had begun.

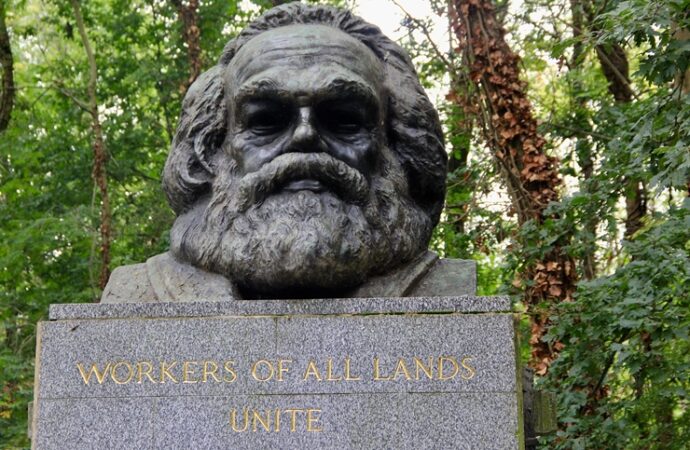

‘Marx’s Ideological Heirs’

On October 25, 1989, a mere two months after Poland’s pivotal election, The New York Times published an article, headlined “The Mainstreaming of Marxism in US Colleges,” describing a strange and seemingly paradoxical phenomenon. Even as the world’s great experiment in Marxism was collapsing for all to see, Marxist ideas were taking root and becoming mainstream in the halls of American universities.

“As Karl Marx’s ideological heirs in Communist nations struggle to transform his political legacy, his intellectual heirs on American campuses have virtually completed their own transformation from brash, beleaguered outsiders to assimilated academic insiders,” wrote Felicity Barringer.

There were notable differences, however. The stark, unmistakable contrast between the grinding poverty of the Communist nations and the prosperity of Western economies had obliterated socialism’s claim to economic superiority.

As a result, orthodox Marxism, with its emphasis on economics, was no longer in vogue. Traditional Marxism was “retreating” and had become “unfashionable,” the Times reported.

“There are a lot of people who don’t want to call themselves Marxist,” Eugene D. Genovese, an eminent Marxist academic, told the Times. (Genovese, who died in 2012, later abandoned socialism and embraced traditional conservatism after rediscovering Catholicism.)

Marxism wasn’t truly retreating, however. It was simply adapting to survive.

Watching the upheaval in Poland and other Eastern bloc nations had convinced even Marxists that capitalism would not “give way to socialism” anytime soon. But this would cause an evolution of Marxist ideas, not an abandonment of them.

”Marx has become relativized,” Loren Graham, a historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told the Times.

Graham was just one of a dozen of the scholars the Times spoke to, a mix of economists, legal scholars, historians, sociologists, and literary critics. Most of them seemed to reach the same conclusion as Graham.

Marxism was not dying, it was mutating.

”Marxism and feminism, Marxism and deconstruction, Marxism and race – this is where the exciting debates are,” Jonathan M. Wiener, a professor of history at the University of California at Irvine, told the paper.

Marxism was still thriving, Barringer concluded, but not in the social sciences, “where there is a possibility of practical application,” but in abstract fields such as literary criticism.

A Strategic Shift

Marxism was not defeated. The Marxists had just staked out new turf.

And it was a highly strategic move. “Practical application” of Marxism had proven disastrous. Communism had been tried as a governing philosophy and had failed catastrophically, leading to mass starvation, impoverishment, persecution, and murder. But, in the ivory tower of the American university system, professors could inculcate Marxist ideas in the minds of their students without risk of being refuted by reality.

Yet, it wasn’t happening in university economics departments, because Marxism’s credentials in that discipline were too tarnished by its “practical” track record. Instead, Marxism was thriving in English departments and other more abstract disciplines.

In these studies, economics was downplayed, and other key aspects of the Marxist worldview came to the fore. The Marxist class war doctrine was still emphasized. But instead of capital versus labor, it was the patriarchy versus women, the racially privileged versus the marginalized, etc. Students were taught to see every social relation through the lens of oppression and conflict.

After absorbing Marxist ideas (even when those ideas weren’t called “Marxist”), generations of university graduates carried those ideas into other important American institutions: the arts, media, government, public schools, even eventually into human resources departments and corporate boardrooms. (This is known as “the long march through the institutions,” as coined by the early twentieth-century Marxist theoretician Antonio Gramsci.)

Indeed, it was recently revealed that federal agencies have spent millions of taxpayer dollars on programs training employees to acknowledge their “white privilege.” These training programs are also found in countless schools and corporations, and people who have questioned the appropriateness of these programs have found themselves summarily fired.

A huge part of today’s culture is a consequence of this movement. Widespread “wokeness,” all-pervasive identity politics, victimism, cancel culture, rioters self-righteously destroying people’s livelihoods and menacing passersby: all largely stem from Marxist presumptions (especially Marxism’s distorted fixations on oppression and conflict) that have been incubating in the universities, especially since the late 80s.

As it turned out, what was happening in American universities in 1989 was just as pivotal as what was happening in European parliaments.

Especially in an election year, it can be easy to fixate on the political fray. But the lesson of 1989 is that today’s culture and ideas are tomorrow’s politics and policies.

That is why the fate of freedom rests on education.

—

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

Image Credit:

Pixabay

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *