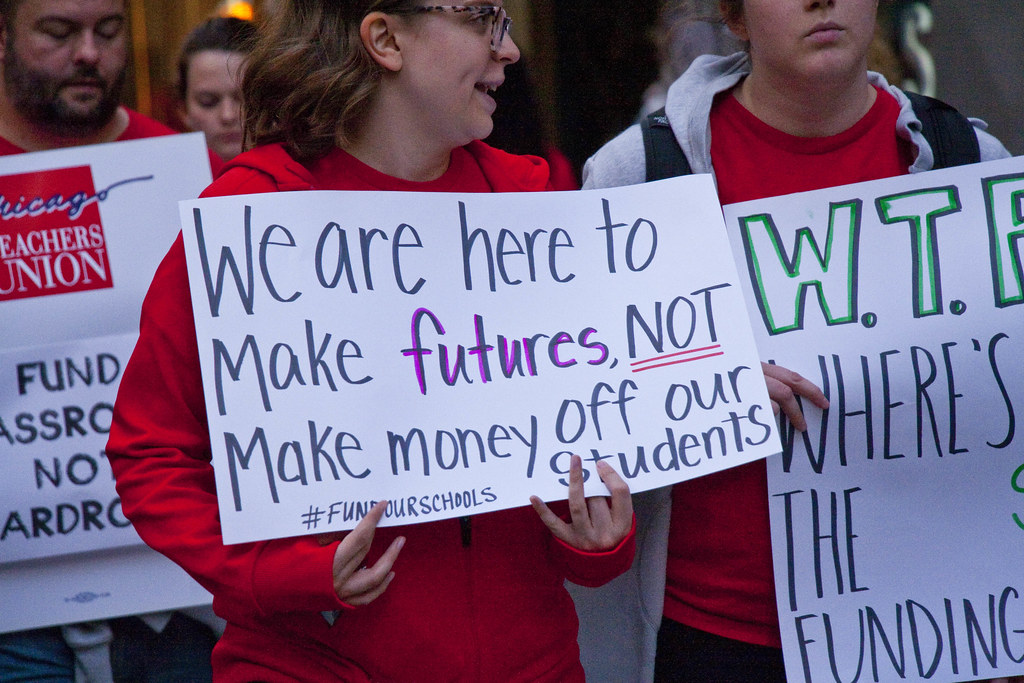

Classes in Chicago’s public schools were canceled starting Oct. 17 as more than 25,000 teachers in the nation’s third-largest school district went on strike in what they’re calling a fight for “justice and equity” for their students.

The strike, the city’s first in seven years, marks what has been a tumultuous year for labor negotiations in urban school districts around the country. Thirty thousand Los Angeles school teachers went on a six-day strike in January. The next month, approximately 2,600 teachers walked out of the classroom for three days in Denver, and 3,000 teachers picketed for a week in Oakland.

Many of the demands the unions are making almost certainly would benefit students. But beneath the rallying cries, these unions are facing a new reality that suggests they are also fighting for something else.

In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled in Janus v. AFSCME that workers are free to choose whether to join a union. Since then, we’d argue, teacher strikes have been as much a fight for the soul of the union as they are for the soul of public education. What the teachers’ unions want and need is membership.

The deals that teachers’ unions negotiate with school districts matter more than ever for maintaining their membership and political power in the post-Janus world. As education policy scholars who have studied teachers’ unions and teacher collective bargaining for more than a decade, we have read thousands of agreements like the ones negotiated in Los Angeles, Denver and Oakland in early 2019 and will soon be forged in Chicago.

Negotiating for numbers

What does negotiating for membership look like?

The agreements that unions are securing establish teacher salaries, restrictions on the length of the workday, performance evaluation procedures and other important working conditions. But they also set staffing levels for teachers, librarians, nurses and counselors. In short, teachers are bargaining to increase staffing – and in particular, staff who can also join the union. If they can increase staffing, they can increase membership and ensure their future.

With a 16% raise on the table, the Chicago Teachers’ Union is asking for a contract that guarantees smaller class sizes. With fewer students in each classroom, the school system will need to employ more teachers. In addition, the union aims to increase the number of nonteaching staff employed, such as nurses, librarians, social workers and counselors. All of these new hires will be potential union members.

Consider the three-year deal that the teachers’ union secured in Los Angeles in January. Along with a 6% salary increase, the deal included numerous staffing guarantees that equate to more membership for the Los Angeles teachers’ union: 300 nurses, 82 librarians and 77 counselors. Because the contract reduced class size by four students in grades 4 through 12 over the duration of the contract, it requires the school district to add new teachers.

The Oakland teachers’ union followed a similar playbook for their four-year deal in February. The union secured an 11% raise over the next four years and a modest reduction in class size by the 2021-22 school year. Additionally, the new contract lowers the counselor-to-student ratio, establishes new caseload limits for school psychologists and speech and language pathologists and increases staffing levels at schools with 50 or more students who are new to the country.

All of those provisions require the district to add more educators.

Organizing charter school teachers

Not only are teachers’ unions fighting for increased staffing levels, they are using contract negotiations to limit the transfer of teachers to nonunion schools that pose a threat to their membership levels.

The unions in Los Angeles and Oakland took a hard stance on charter schools in their negotiations. In Los Angeles, the teachers’ union called for an eight- to 10-month moratorium on new charter schools, something the local school board cannot provide. However, the Los Angeles Unified School District agreed to endorse such a moratorium and lobby California’s governor to that end.

The Oakland teachers’ union secured a nearly identical commitment from the school district to lobby the state legislature for the same moratorium. A final union-backed bill, which stopped short of a full stop on new charters but which imposed new restrictions, received the California governor’s signature in October. The Chicago teachers’ union secured a cap on charter school expansion in their last contract negotiations in 2016.

Even while they attempt to limit charter growth, unions are seeking to organize charter teachers. The teachers at more than a quarter of Chicago’s 121 charter schools belong to the Chicago Teachers’ Union. A similar share of the 277 charter schools in Los Angeles are organized by its teachers’ union. Only two of Oakland’s 44 charters, however, are unionized.

The teachers at some of the charter schools in Chicago and Los Angeles went on strike in the past year, for the first in the nation’s history.

All in all, our rough calculations suggest that the staffing provisions in the Los Angeles contract could have added over 1,500 members to the the Los Angeles teachers’ union’s membership. This would equate to about a 5% increase in the union’s ranks of at least 30,000 educators. The Oakland teachers’ union could be getting a similar boost.

Gaining members

It’s too early to tell what will happen in Chicago, but a contract with robust staffing guarantees will likely add membership to the union ranks.

In a post-Janus world, unions are showcasing the viability of the picket line as a way to win contracts that bolster membership. Not only that, but because only union members can vote to authorize a strike, union leadership can leverage strike votes to petition – or pressure – nonunion members to join the movement.

The Los Angeles union reports adding over 1,000 members during its strike vote. The Denver union says it added 250 during its authorization vote.

So why are teachers’ unions striking with increased frequency? We believe that unions are fighting for their survival.

![]()

—

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

[Image Credit: flickr-Charles Edward Miller, CC BY-SA 2.0]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *