As I write these words, a reproduction of the 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue, published in 1968 by Chelsea House, sits at my elbow.

The fat catalog is a casual reader’s delight and a historian’s treasure trove. Here are medicines like laudanum, herb tea, and castor oil. Here are tools, bobsleds, gasoline stoves, windmills, bicycles, clothing and footwear, valises, books, clocks and watches, fountain pens, banjos and snare drums, furniture and cutlery, buggies and wagons. (The price of most surreys is under $100, a belt is fifty cents, a child’s high chair a dollar, a ball room guide for gentlemen twenty-five cents.)

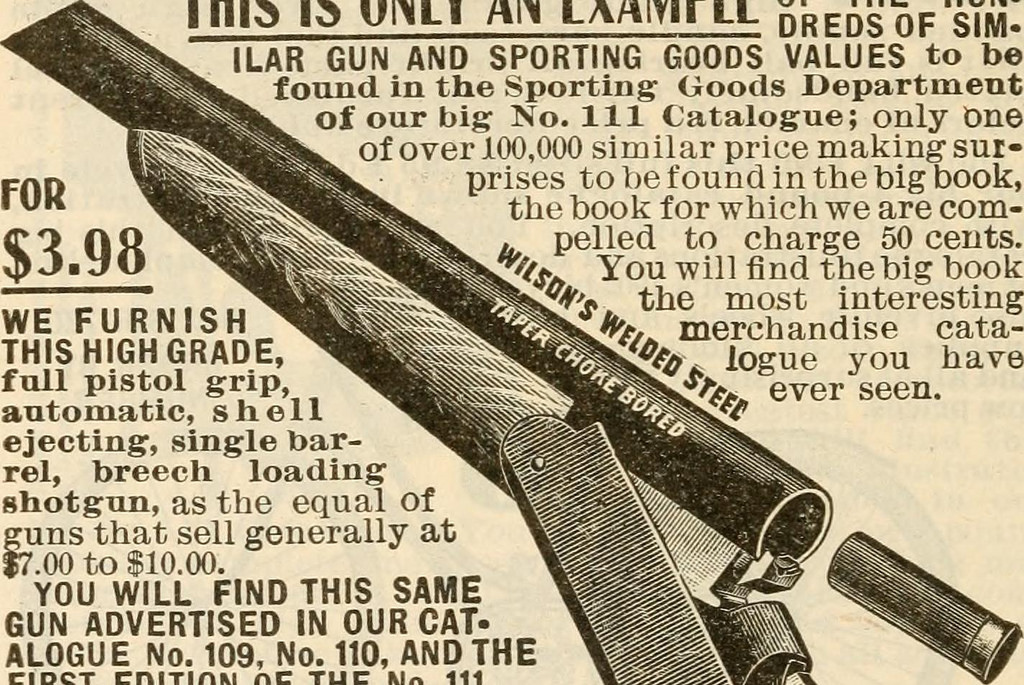

And in the Sporting Goods Department we find 28 pages of guns, ammunition, and accessories.

Here we have weapons ranging from the Daisy Air Rifle to “Our $1.55 Revolver,” from shotguns for $7.95 to Marlin Repeating Rifles. Sears, Roebuck & Company also sold ammunition, pistol holders, reloading tools, and cleaners for these weapons.

No one was monitoring these sales. The government had no part in regulation. No one conducted background checks on the buyers. Indeed, Sears brags that it is “the headquarter for everything in guns,” that their prices are below all others, and that “we will send any revolver to any address.”

Yikes, right? Even a common laborer, for three or four days wages, could order a Saturday night special from Sears. With guns and ammo so easily available, we might guess that the streets of every American city and town were running red with blood every day of the week. Mass murder surely occurred on a weekly basis. Assassination and terrorist attacks must have happened so regularly that no one blinked an eye.

We might guess so, but we would be wrong.

In 1900, the number of murders and “non-negligent homicides” in the United States was approximately 1 in every 100,000 inhabitants (This figure and the others in this paragraph include all murders, not just those by firearms.) In 1980, that figure was close to 11 murders per 100,000 people. Since then, that figure has declined to between 4 and 5 murders per 100,000. (For a deeper analysis, see here.) Bear in mind too that unlike today, a gunshot wound in 1900 frequently resulted in death.

These statistics contrasted with the easy availability of guns should raise some questions. Why in 1900, when firearms were so readily accessible, were murders so infrequent? Why are murders today quadruple what they were in 1900? Based on what gun-control activists tell us, shouldn’t we expect the exact opposite?

Doubtless such questions might provoke many responses. They deserve study by investigators whose education, credentials, and research are superior to my own. But surely some obvious reasons account for our higher murder rate. Here are a few of them.

First, our recent ancestors had more respect than we do for human life. People living in 1900 died from diseases and ailments now vanquished. They were more familiar with death than most of us living today. Relatives often died at home rather than in a hospital. In a time of high infant mortality and death due to diseases now casually treated with antibiotics, perhaps each life was regarded as special.

In addition, the men and women of 1900 were not drenched in today’s artificial violence. According to some studies, the average young person will see 200,000 acts of violence in movies and on television by the age of 18. Furthermore, numerous studies show that playing violent video games lead to aggressiveness, especially in young men. Were Mortal Kombat, Postal, and Mad World available to sixteen-year-old Johnny in 1900, perhaps he too would have been more prone to take to the streets with his father’s revolver.

The breakdown of the family, accompanied by the erosion of religious faith and moral teaching in schools and the public square, has surely contributed as well to the increase in gun violence and the murder rate. Young men growing up fatherless, the belief that we can create our own moral code, the move away from the Commandments, including the one enjoining us not to kill, may all contribute to our higher murder rates.

Many citizens today advocate “gun control.” If we restrict or eliminate gun ownership, their argument goes, we will reduce the number of murders. Nevertheless, the puzzle remains: Why were so few of our ancestors shooting one another when guns could be bought as easily as soap, shoes, and slipcovers?

Instead of pointing at firearms as the cause of violence, maybe we should ask: “What sort of people have we become? What part of our humanity have we lost in the past six-score years?”

To steal a construct from Shakespeare: Perhaps the fault lies not in our guns, but in ourselves.

—

Image Credit: Flickr

1 Comment

Karl Ess

November 18, 2024, 6:56 pmRe: the disparity in homicides/100K over time – only my opinion but consider : in early 20th century folks had to mature earlier as necessary to sustain themselves. Very few government agencies existed to care for us. Death was a physical finality and religion taught us that the time for dying was to be chosen by the Supreme Being. Then along came television – 6 guns were seen to contain 600 rounds each, those shot usually had time to be comforted on the chest of a fine woman, and last – those shot to death would magically re-appear the following episode and continue to 'bite da dust'. Sorry but today too many folks live in their own pink tinted bubble and believe that they possess Ponce de Leons' magic potion. And last, drugs (legal & illegal) are much to readily available, preventing people from seeing that 'guns don't kill~ people kill. Cain did NOT kill his brother with a .45acp or 9mm. Guns were not invented until some 4600 years had passed (1364 AD). In the interim, many homicides were perpetuated with Rocks, Sticks, Knives and Poisons, as well as many versions of each of these. With the mindset of far too many people world-wide today, even if EVERY gun were to melt down overnight homicides would would continue to occur

REPLY