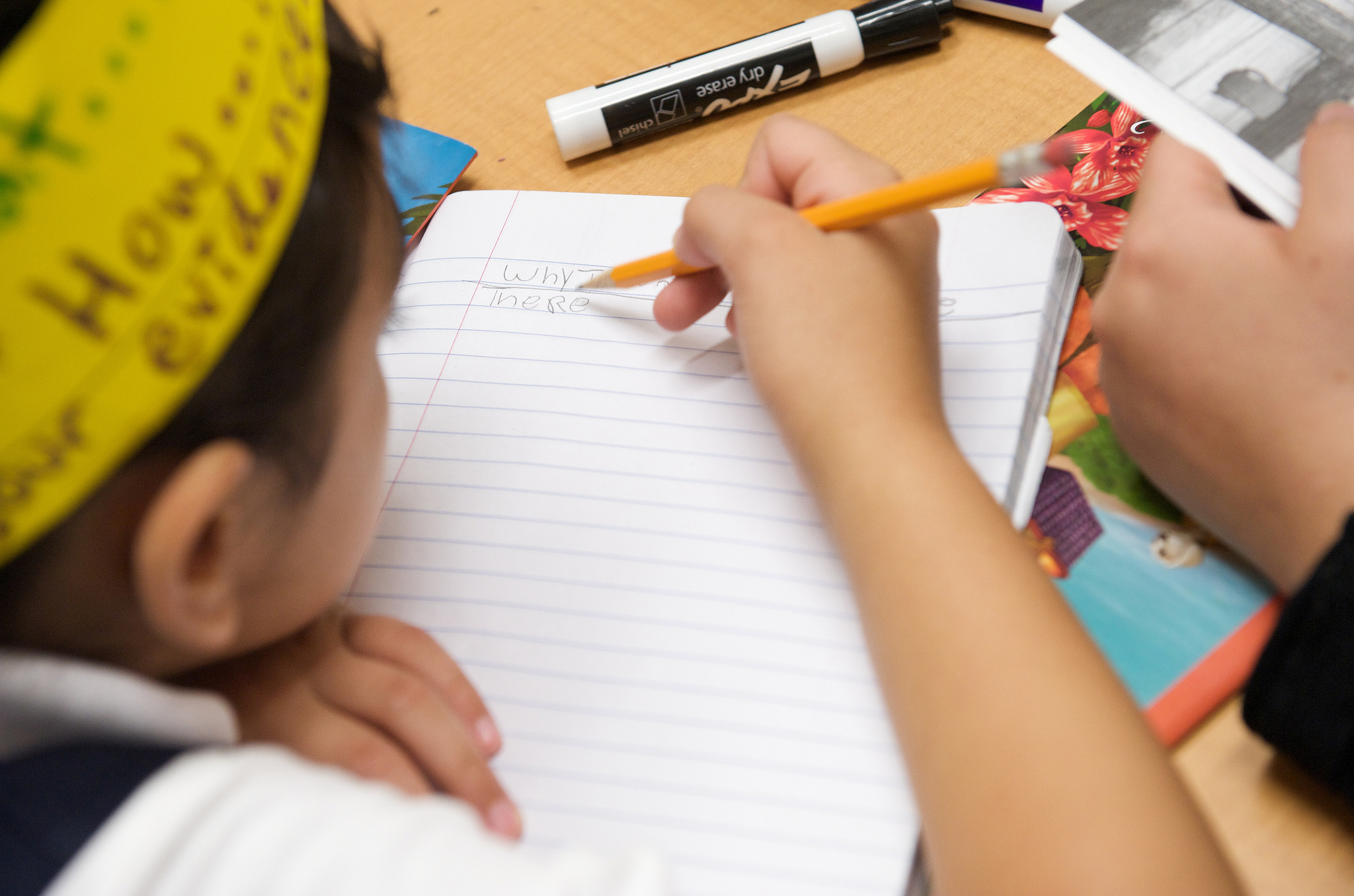

As the decline in education standards in Australia continues, new research conducted by the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) offers a solution.

The study, headed by research fellow Blaise Joseph, examined 18 schools in disadvantaged areas around the country that boast consistent records of above-average academic performance. The study found six common factors across these school that accounted for strong academic results.

Interestingly, additional funding was not a factor. Instead, it was the resurfacing of old-fashioned principles including good discipline, experienced leadership, high expectations, explicit teaching, comprehensive early reading instruction, and the effective use of student data that accounted for the schools’ healthy academic culture.

These schools also “tended to shun the increasingly trendy inquiry-based teaching model,” a “constructivist approach” which also goes by the buzz names “project-based learning,” “design thinking,” and “discovery-based learning.”

Located in areas of the lowest socio-economic quartile, the schools have been mostly outperforming comparable schools.

Of the six factors indicating success, the strongest across all the schools was good discipline. This makes sense in light of another study conducted five years ago by the OECD which recorded that 40 percent of students found classrooms noisy and disorderly, and 20 percent of students found them so disruptive they could not properly do their work.

This is a problem the Government’s school funding legislative changes known as Gonski 2.0 failed to address.

Explicit learning was the other most significant factor, according to Rebecca Urban, who wrote about the study in The Australian (paywall). Unambiguous expectations helped teachers maintain discipline in the classroom. A clear set of classroom routines and rules, consistently applied, proved effective in encouraging good student behavior and accelerating learning, Urban noted.

Explicit learning included “clear objectives, feedback, reviews of previous lessons, frequent checking of student understanding, demonstration of the knowledge or skill learnt, and practice of skills under teacher guidance.” This, says Urban, is in direct contrast with “postmodern” inquiry-based learning which “allows students a lot of leeway.”

On the publication of Urban’s article, online forums were soon flooded by voices corroborating the findings with personal testimonies – or affirming what seems just plain common sense.

Yet, apparently, politicians haven’t got the message.

The existing “spendathon” in the education sector is a prominent feature of pre-election promises. (The federal election is due in May.) Despite injecting tens of billions of extra taxpayer dollars into learning institutes in the past 12 years, both the Australian Liberal and Labor governments have failed to turn around the trend of declining education standards.

Money can’t buy you everything after all. And yet, there’s something positive about that; it can give hope to socially and economically disadvantaged families.

More pointedly though, the study exposes the farcical character of modern learning methodologies. The new evidence in favour of “explicit learning” delivers the implicit message that modern methods such as discovery-based or inquiry-based learning lacks fundamental educational merit.

By emphasizing the importance of “clear objectives,” and “feedback” the study suggests the modern systems of learning lack these attributes. By stressing the need for frequently checking student understanding, it likewise implies modern methods often neglect this hugely important task.

There’s another thing that a return to traditional, structured learning methods does for students; it removes the stress which comes from having total responsibility for a learning task. Inquiry-based learning puts the onus on students to not only learn the lesson at hand, but to formulate it in the first instance.

Having a student following his or her own learning pathway has, no doubt, its attractions for the teacher, who then gets to sit back and watch student learning unfold. The opposite, as many teaching acquaintances of mine repeatedly affirm, is true. The ideal is an illusion.

When 20 children in a classroom are encouraged to let their curiosity and initiative take them where it will, before they have mastered the basic building blocks of learning, the result is restlessness among students. They are lost in tasks they have not been given the intellectual wherewithal to undertake. This evolves into class disruption and fragmented teaching strategies.

The most problematic thing of all is that without clear learning objectives there can be no objective standard by which progress – or regress – can be tracked. This leaves a vacuum in which modern methods are assumed to work.

In addition, when tasks and objectives are articulated within the framework of modern methodology, they are worded in academic gobbledygook that effectively leaves students, teachers and parents confounded. The authors and purveyors of postmodern pedagogies are the tailors who make the emperor’s new clothes.

“Inquiry-based learning” and “design thinking” are the invisible cloth and thread exposing our children’s educational nakedness. Those who venture to call it what it is, are discredited as being too unsophisticated, ignorant and backward to appreciate the newer learning approaches.

Hopefully, this new study, which is already grabbing the attention of American policy-makers, will further encourage those who are dissatisfied with the current system but lack the data and words to demand better.

—

This article was republished with permission from Mercator Net.

Dear Readers,

Big Tech is suppressing our reach, refusing to let us advertise and squelching our ability to serve up a steady diet of truth and ideas. Help us fight back by becoming a member for just $5 a month and then join the discussion on Parler @CharlemagneInstitute and Gab @CharlemagneInstitute!

Image Credit:

Flickr- US Department of Education , CC BY 2.0

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *