Several years ago, a bright 25-year-old told me about her time tutoring those taking the SAT tests in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She worked hard to prep young people for these college admissions tests, demanded much of her students, and set the bar high for herself and them.

One young man, a wealthy foreign-born student, did few of the assignments. Again and again, on his practice tests, he scored abysmally low. She fretted over his lack of effort and nagged at him, but he seemed unconcerned.

Then came the tests. The kid walked away with a score that could put him into any Ivy League school in the nation. “I’m sure he paid someone to take his test,” the woman told me.

Recently, U.S. attorneys busted over fifty wealthy Americans for paying bribes to SAT or ACT administrators, or to sports coaches, to have their children admitted to highly competitive schools. William Rick Singer, a Californian who ran Key Worldwide Foundation, received more than $25 million from these parents seeking help with the admissions process. Singer would then bribe various administrators and coaches, and the student would be admitted to college. Those accused of these crimes include actresses Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin.

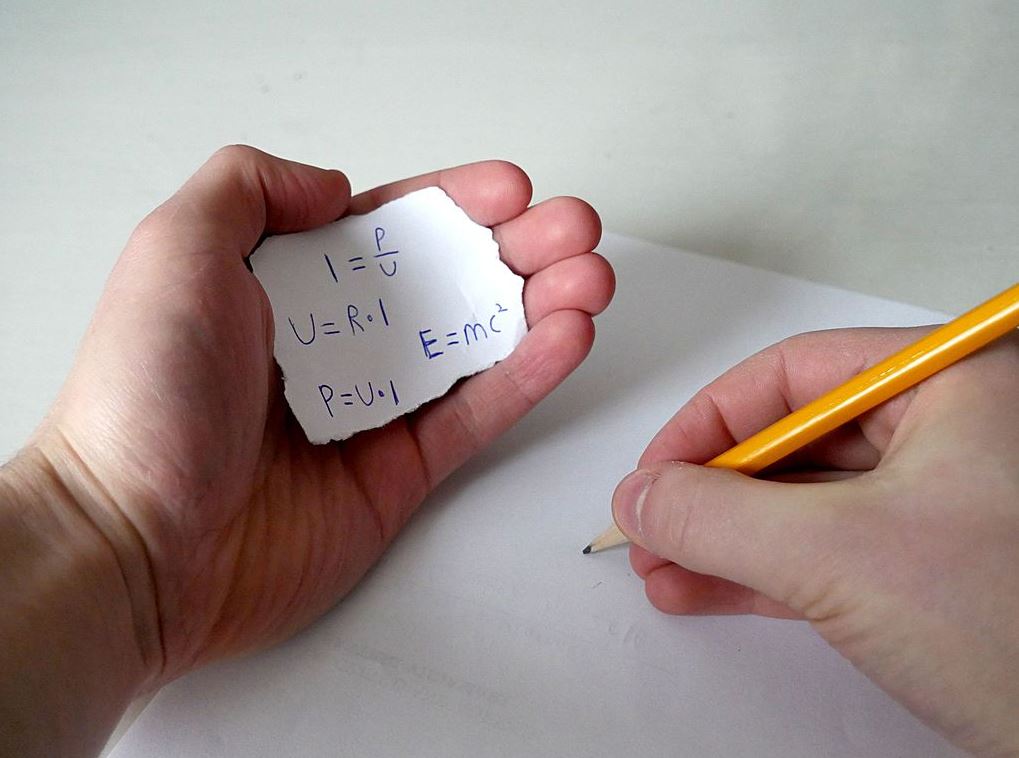

But students don’t need wealth to cheat on standardized tests. Just look up Quora and one will find all sorts of tricks and tips for cheating on the SAT.

Meanwhile, cheating on such tests as the SAT, ACT, and GRE is rampant among Chinese students seeking admission to American colleges and universities. In her Atlantic article, “How Sophisticated Test Scams from China Are Making Their Way Into The U.S.,” Peg Tyre examines this scandal in depth, telling us of the “gunmen,” as they are called, who are paid to take another student’s test. She writes:

Chinese-language websites advertising the services of test-taking proxies in the U.S. are flourishing. “These services are not exactly underground,” says New York-based defense lawyer Anna Demidchik, whose firm represented a wealthy University of Connecticut student, Quifan Chen, who recently pleaded guilty to having a gunman take his GREs in December 2014 and using them to apply to top business schools. “Some brokers will only take clients if they are referred by another student,” Demidchik said. “Others will take customers after a brief electronic negotiation.” In an effort to show how pervasive the cheating scams were, Demidchik recently had her paralegal, who is fluent in Chinese, negotiate with a broker to obtain prices for U.S.-based test-taking proxy online. The proxy companies, she points out, exist to meet a demand. “Middle-class and wealthy Chinese parents are putting enormous pressure on their children to gain admission to prestigious U.S. colleges,” she said. “Add to that, there is a cultural disconnect—many Chinese families don’t realize how seriously Americans take these kind of infractions.

Yes, we do take those infractions seriously. Up to 2,000 students per year are caught and punished for cheating on the SAT alone, which is a handful compared to the hundreds of thousands of students who take the test.

But maybe we don’t take the infractions seriously enough.

Students who hire substitutes to take their tests, and the substitutes themselves, will find themselves in hot water with the law for committing fraud. But students found or suspected of cheating by other means only have their test scores cancelled, with no repercussions from their high school, no report to the admissions committee of the college they wish to attend.

Unfortunately, such fraud extends beyond these standardized tests. One study recently revealed that nine out of 10 college students admitted to cheating on their exams and papers.

Only 300 students in this study were asked about cheating, which seems statistically small. But even if we cut the figure to five in 10 cheaters, we are left with a significant number of people who will enter the work force having swindled their way through difficult courses.

For twenty years, I was a teacher. I did nab some students cheating on tests or plagiarizing their papers from the Internet, and I suspected others, including a few who took Advanced Placement tests in such subjects as English Composition and US History. Their high scores came nowhere near their practice tests or their performance in class.

As I write these words, I am thinking of one young man in particular who wanted to follow his father into medicine. If I ever go under the knife for open-heart surgery, a brain tumor, or some other dire procedure, I would hope to heaven he is not the one who leans over me as I lie on a gurney to say, “Hello, Mr. Minick. Good to see you. I’ll be your surgeon today.”

—

Dear Readers,

Big Tech is suppressing our reach, refusing to let us advertise and squelching our ability to serve up a steady diet of truth and ideas. Help us fight back by becoming a member for just $5 a month and then join the discussion on Parler @CharlemagneInstitute and Gab @CharlemagneInstitute!

Image Credit:

Santeri Viinamäki CC BY-SA 4.0

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *