G. K. Chesterton, the journalist, did much of his writing for newspapers. Not surprisingly, he was also an inveterate reader of newspapers, and on more than one occasion a newspaper headline sparked one of his essays for the Illustrated London News. One example of this is a headline that read: “Darwinism Is Still True.”

Chesterton was struck by the headline’s tone of shaky insistence. It surely was a strange way to express confidence in the truth of a “thoroughly established truth.” If Darwinism was true, did it need to be touted as “still true?”

Chesterton had no doubt that there were thoroughly established scientific truths. William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of blood was his immediate example. Because it was and is true, Chesterton couldn’t imagine a headline declaring that the “circulation of the blood [is] still true.”

For Chesterton, this particular truth was true less because the “great Harvey” had proved it than because “we” have proved it. By “we” Chesterton meant the “great mass of mankind.” Its acceptance, after all, is the “ultimate mark of a genuine and valid scientific discovery.”

Then and now, we know that blood circulates in the body. But do we know that Darwinian evolution is true? Unlike evolution, the truth of the circulation of blood is always being tested in all sorts of ways. As a result, “millions of morons” know that it is actually true. Therefore, there is no need for a headline to shout that Harvey’s discovery is “still true.”

Darwin’s defenders, then and now, insist that he was—and still is—right, even as they continue to concede that his missing link is still missing. Chesterton thought that the absence of this yet-to-be-discovered link actually understates the problem for those who hold to Darwinism.

Chesterton did concede that there are “traces of creatures” that might possibly have grown out of other creatures. But there is nothing even approaching a trace of any creature actually growing out of another creature. At least nobody has ever “caught them at it.”

And yet Chesterton was still not finished making concessions. While Darwinian evolution may not be a truth, he agreed that it was a hypothesis, maybe even a not unreasonable hypothesis. As such, this or any hypothesis may “hold the field,” without being finally established, when either of the following conditions is met: 1) when we are able to conclude that it does cover many of the facts; 2) or when no other hypothesis covers any of the facts, or even “any adequate proportion” of them.

Chesterton, the logician, then asked the next logical question: Is the Darwinian hypothesis the sort of hypothesis that does, in fact, hold the field? He thought not.

Chesterton did not deny that the Darwinian hypothesis had its uses. After all, it was—and remains—the “only atheistic explanation for the usefulness of feathers.” In sum, the “very ingenious theory of Darwin sought to evade the old argument from Design.” But did it succeed? Once again, Chesterton thought not.

In fact, neither Charles Darwin nor anyone since Darwin has been able to concoct any possible way whereby the “obvious appearance of design could have come about without a Designer.”

Darwin or no Darwin, the person today who denies a designer is in exactly the same position as any doubter or disbeliever was hundreds, even thousands, of years before Charles Darwin was alive and thinking. Therefore, Chesterton’s headline on the subject of Darwinian evolution would read as follows: “Despite Darwin, God Is Still True.”

—

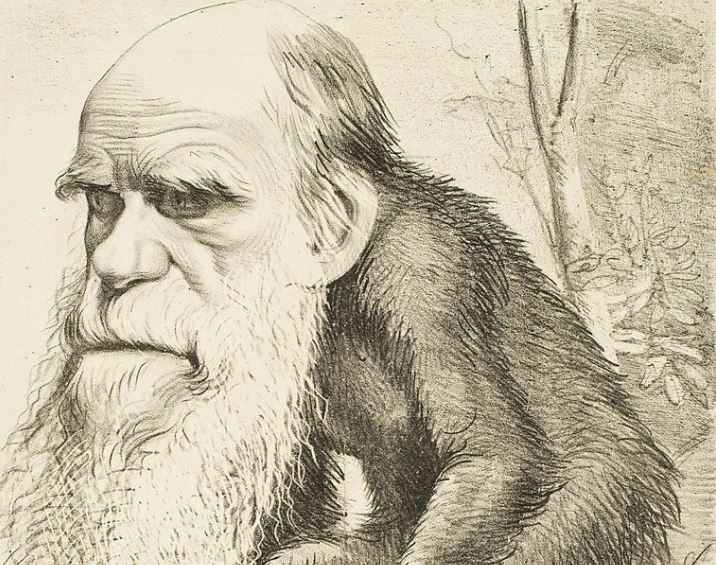

[Image Credit: Desconegut, Public Domain (cropped)]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *