Tonight, the second-most-popular televised football broadcast of the year takes place from New York’s Radio City Music Hall. ESPN will broadcast round one of the NFL Draft, with the remaining rounds to be broadcast on Friday and Saturday. An estimated 40 million people will watch the draft, an event that even for the most interested fan moves at a snail’s pace.

“We all thought, way back when, how can this become the most watched non-movement sporting event in professional sports?” former NFL executive Carl Peterson says. “That’s what it is. Nobody’s moving. We’re just drafting. Now it’s prime time. Thursday night!”

The draft has come a long way since beginning in 1936, when teams selected players based on rumors and gut feelings. Now the business of drafting is big business, and the business of scouting and projecting what teams will pick which players is equally big.

In 1979, the brand new ESPN petitioned the league to televise the draft live. The network was initially turned down by a unanimous vote of the league owners. But ESPN persisted, and in April 1980, the cameras rolled as Oklahoma running back Billy Sims was selected first by the Detroit Lions on an early Tuesday morning.

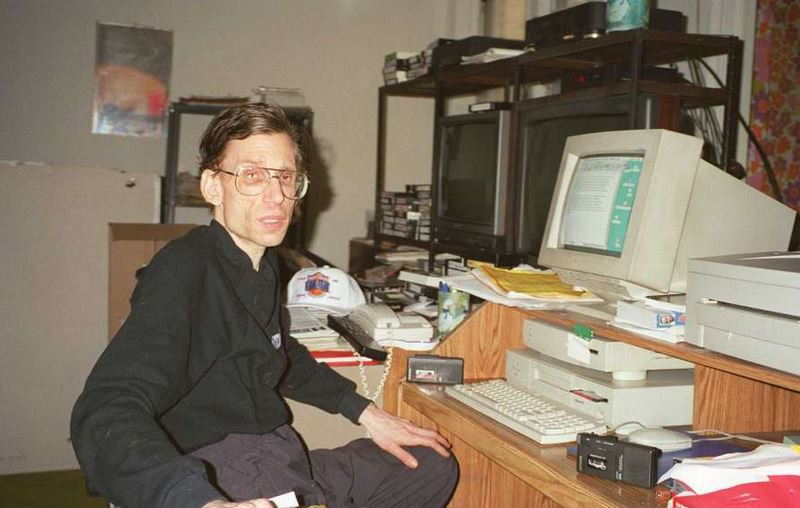

But it was one man’s work that provided the inspiration to televise the draft, leading to an entire industry that revolves around pro football’s spring ritual. Joel Buchsbaum was a small, frail recluse who left his apartment in Brooklyn only to walk his dog, visit his mother, or go to the gym. He would leave Brooklyn only once a year — to attend the NFL draft in Manhattan. But the five-foot-eight-inch, 100-pound Buchsbaum was a giant in player analysis, who, as Dallas Morning News reporter Juliet Macur writes,

could tell you anything about football, anything about players — even from 10 years ago. Heights. Forty-yard dash times. Injuries. If a guy sprained an ankle, he knew which ankle.

When a Police Athletic League coach told Buchsbaum he was too small to play sports he began a lifelong obsession with player analysis.

Buchsbaum wrote for Pro Football Weekly and each year produced an analysis of each of the 600 to 800 players available for the draft that NFL insiders considered the definitive draft guide. With his nasal Brooklyn monotone, he also became a cult figure on weekly radio programs in Houston and St. Louis.

Most people had no idea what Buchsbaum looked like. He turned down all lunch and social requests. Yet he was phone friends with NFL brass around the league. Bill Belichick, Al Davis, and Bobby Beathard were buddies, as was New York Giants general manager, Ernie Accorsi, who said, “There weren’t a lot of people who influenced all these top people in the league like Joel did.”

“I was never in his presence. That puts me in the same category as 99 percent of people that knew him,” said NBC sportscaster Bob Costas, who hosted a St. Louis radio show with Buchsbaum in the late 1970s. “A sighting of him was like a sighting of Bigfoot.”

His apartment was so messy, his mother refused to visit. He used his bathtub to store books. The gas was turned off to his stove. The air conditioner didn’t work. But from there he worked 80 to 90 hours a week, never taking a week off. He often watched and recorded three games at once, and racked up phone bills as high as $1,500 a month talking to his sources.

Buchsbaum wrote his first draft report at age 20 and sent it out to 120 newspapers and magazines hoping to get published. The next year he was hired by the Football News.

In 1978 Pro Football Weekly hired him to generate a 50-page draft analysis. Over the years these reports grew to over 200 pages.

One wonders how on earth a person could make a living analyzing football players and their potential pro careers. But that is the beauty of the division of labor. With people specializing in what they do best and cooperating with others, efficiencies are gained and everyone is better off. Murray Rothbard explains in Man, Economy, and State, “the further an exchange economy develops, the further advanced will be the specialization process.”

Rothbard points out that the marketability of products and services determines how extensive the division of labor is in a society. If the exchange economy is allowed to thrive, the potential for specialization is endless. New technologies and services beget more advances and further opportunities for specialization.

Writes Rothbard,

It is clear that conditions for exchange, and therefore increased productivity for the participants, will occur where each party has a superiority in productivity in regard to one of the goods exchanged — a superiority that may be due either to better nature-given factors or to the ability of the producer. If individuals abandon attempts to satisfy their wants in isolation, and if each devotes his working time to that specialty in which he excels, it is clear that total productivity for each of the products is increased.

The National Football League draft is a television spectacular for pro-football fans starved for action since the final gun went off at the Super Bowl. The draft is a celebration of hope as the worst teams in the league get first choice of the best players coming out of college. The Indianapolis Colts’ dismal 2011 season makes Peyton Manning’s ex-team the star of the festivities with the number-one pick.

There will likely be no drama with that pick being Stanford’s Andrew Luck, and virtually everyone has Heisman Trophy winner Robert Griffin III (RG3) going next to the Washington Redskins. But stranger things have happened. Subjective values among NFL coaches and front offices are different. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

F.A. Harper explains why there is a difference of opinion concerning the pro potential of college players.

The first step in understanding the Austrian concept is to realize that value is entirely subjective, rather than something objective. Value, therefore, is something that each individual person weighs on a purely private, not a public, set of scales.

Harper continues:

Hence, any two persons will not and need not agree on the value of the same item at the same instant of time. If they should agree, it is a coincidence of no significance whatever so far as discovering value objectively is concerned. For any item at any given instant of time, each person sets his own value in a way that is a mystery to others. He takes into account a vast range of considerations, many of which are peculiar to him alone and which may be so deeply subjective that he cannot even describe them to another person.

NFL teams don’t bid against each other monetarily to draft individual players. What sets the value of the player is where he is drafted. Using a first-round selection to pick untested college talent is riskier and more “expensive” than using a second-round pick, and so on.

Winning in the NFL attracts fans, sells merchandise, and increases franchise value. For example, the difference between drafting Peyton Manning #1 and Ryan Leaf #2 in 1998 boggles the imagination. Manning went on to lead Indianapolis to seven AFC South Championships, two AFC Championships, and a Super Bowl win, while earning four league MVP awards. And after sitting out last year due to injury, Manning will play next year for Denver at age 36.

Ryan Leaf, drafted a few minutes after Manning by the San Diego Chargers, is considered the biggest flop in NFL draft history. The Chargers signed the college star to a four-year contract of $31.25 million, which included a $11.25 million signing bonus. Leaf was benched after 9 games in his rookie year due to poor performance. He missed his second season due to an injury, and in 2001 San Diego let him go. Leaf was given tryouts by a few teams, but at age 26 he retired from the game.

This all makes the NFL draft intriguing to fans — draftniks — everywhere. There are hundreds of websites, magazines, and television programs devoted to analyzing players and projecting the outcome of the draft. Mock drafts are everywhere, and a cottage industry — currently led by Mel Kiper Jr. — has developed beyond anyone’s expectation.

In 1981, 21-year-old Kiper sold his draft report to the public for the first time, after placing an ad in a football magazine. He had 130 orders. Now, Kiper has thousands of customers and is the face of ESPN’s gavel-to-gavel draft coverage.

Kiper and his wife run what the New York Times calls “a sprawling draft empire, replete with radio spots, television shows, books, newsletters and Web sites.” Kiper spends hours on the phone with college coaches and NFL general managers, and more hours watching games learning everything he can about pro prospects. “They have no team of scouts, no ghostwriters, no secretary, no accountant, no technology department,” just Mel and his wife, who handles the business side.

“Thirty-two years ago, people looked at me and said, ‘What? Are you nuts, writing about football players and projecting draft choices and whatever?'” says Kiper, who has been part of ESPN’s draft coverage team since 1984. “The interest is unbelievable right now. Prime time draft? If you would have said that 32 years ago…”

Mr. Kiper has a constant presence on sports television from the start of football season through the draft, and it was Buchsbaum who paved the way. “Draft day is now the second biggest day of the year behind the Super Bowl,” Ernie Accorsi told the New York Times the day after Buchsbaum died in 2002 at age 48. “Joel had a lot to do with what became the glorification of draft day. ESPN started putting it on the air live, but Joel helped them get interested in it.”

Although he hadn’t made 50, Buchsbaum looked 80 when he passed. The only food in his cupboards: 500 cans of mushrooms, some popcorn, and 100 bottles of Diet Sprite. “He was always too busy to eat, so he never ate,” said his mother, Fran Buchsbaum. “With him, it was football, football, football. He thought it was all he needed.”

“He had demons inside of him,” an NFL executive told the Dallas Morning News. “Because he was always afraid of failure. He was scared because he said he wasn’t trained for anything else.”

Only a dozen people attended Buchsbaum’s funeral on New Year’s Eve 2002. Among the mourners were Scott Pioli, who was then the New England Patriots’ vice president of player personnel, and Patriots head coach Bill Belichick, who tried to hire the draft savant more than once. “He knew the players better than any scout for any team,” Belichick said. “Studying film is crucial, and that’s why he was so good. He did it 24 hours a day.”

Fran Buchsbaum never understood what her son did all alone in his apartment. But, after his death, notes from admirers came pouring in. “I had no idea. Every one of these people says he was a genius. I’ve never heard of these men, but look here, an NFL general manager said he was a legend. I guess he would know.”

The division of labor creates organized society. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates says that specialization is advantageous, because “we are not all alike; there are many diversities of natures among us which are adapted to different occupations.”

In Human Action, Ludwig von Mises wrote that the division of labor unifies people: “It makes friends out of enemies, peace out of war, society out of individuals.” And it creates opportunities for the quirky and obsessed.

Mel Kiper Jr. and Joel Buchsbaum were able to create niches for themselves and become legends doing what they love — thanks to the market economy and the glorious division of labor.

—

This Mises Institute article was republished with permission.

[Image Credit: John McClain, Houston Chronicle]

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *