It’s official, folks: the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is ‘post-truth’. What is the meaning of this Orwellian-esque concept?

The definition appears straightforward: “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

The term ‘post-truth’ isn’t new though. It’s been kicking around our lexicon for almost twenty years. Usage of the term spiked around the time of the Brexit vote and in the lead-up to the U.S. presidential election (see graph below, courtesy of Oxforddictionaries.com).

‘Post-truth’ isn’t the only neglected word to make a comeback. Donald Trump’s odd pronunciation of ‘big league’ gave new life to the old term ‘bigly’. However, it’s such an ugly word, most English speakers are too embarrassed to utter it in public. I know I am.

In his book Language, Truth and Logic, English philosopher A.J. Ayer argued in favor of a verificationist principle of meaning: the only meaningful statements are those that can be proven logically or verified scientifically. Perhaps the opposite of the post-truth reality we now inhabit is a world modeled after Ayer’s principle. Yet most of us wouldn’t wish to live in such a world. Almost all of the greatest wonders of this world—speculative truths about human nature, metaphysics, transcendence and the divine—would become meaningless, since they are, you guessed it, logically unprovable and scientifically unverifiable.

In an article for National Public Radio, philosopher Alva Noë claims that the recent popularity of the word ‘post-truth’ is a worrying sign of our growing indifference to the truth:

Perhaps this is how Trump supporters feel when fact-checkers challenge his claim that he’s a great businessman or that he’s very, very rich. They don’t care whether he’s right; they like the fact that he feels great, that he feels rich. Ditto regarding Obama and ISIS, Hillary Clinton and birtherism, the Chinese and “the hoax” of climate change.

Many Americans interpret Trump’s statements loosely. For instance, when Trump recently tweeted that “millions of people who voted illegally” cost him the popular vote, he didn’t mean it literally. Trump was just expressing himself with that unique style of bravado, that über-confidence which intimidates his critics and impresses his base. Obviously Trump is still in election mode.

In “Art of the Lie,” the editors at the Economist connect post-truth with Trump-inspired populism:

Mr. Trump is the leading exponent of “post-truth” politics—a reliance on assertions that “feel true” but have no basis in fact. His brazenness is not punished, but taken as evidence of his willingness to stand up to elite power.

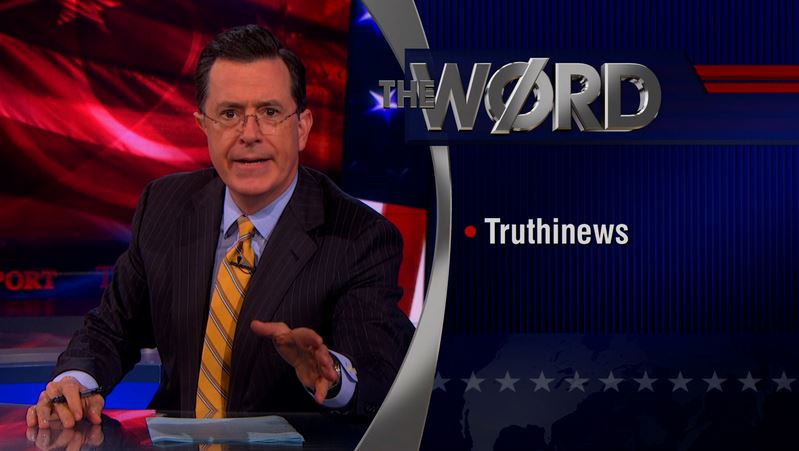

In some ways ‘post-truth’ resembles a term comedian Stephen Colbert coined: ‘truthiness’. Defined as “the belief in what you feel to be true rather than what the facts will support,” it was once used to describe the assertion that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction. It also applies to Google’s claim that driverless cars make us all safer (unless of course you’re riding a bicycle).

Colbert has objected that post-truth is just a ‘rip-off’ of truthiness. I’m skeptical. Erin Keane at Salon is too: “With truthiness … we still recognized that truth exists [ … but in] November 2016, truthiness sounds positively quaint. We’re in the ‘post-truth’ era now, baby.”

Must we abandon truth and logic in this new era of post-truth? Can we strike a healthy balance between the worldviews of Ayer and Trump?

Perhaps ‘post-truth’ is shorthand for saying, ‘when it comes to politics, love and war, sometimes we just prefer to be lied to.’

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *