The internet is abuzz with news of Amazon grocery stores, which will allow customers (using the Amazon Go app) to walk in, grab their groceries, and leave without having to check out.

Reports say that Amazon eventually plans to open more than 2,000 such stores (though Amazon denies the claim). If that in fact did happen, it will likely result in the elimination of a large number of jobs in the grocery industry.

A recent New York Post article notes:

“It also threatens countless jobs at grocery stores, which are the leading employers of cashiers and had 856,850 on their payrolls in May 2015, according to the latest figures from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Britt Beamer, president of America’s Research Group, a consumer-behavior research and consulting firm, estimated that Amazon’s cutting-edge technology had the potential to wipe out 75 percent of typical grocery-store staff.”

Similar pushes toward automation threaten other industries: many fast food employees will most likely be replaced by kiosks; the nation’s 3.5 million truck, cab, and other professional drivers may be replaced by self-driving vehicles; and robots will continue to replace human workers in the manufacturing industry.

And it’s all in the name of technological “progress” and “efficiency”.

Many wonder if the push to eliminate jobs through automation is a case of prioritizing one form of progress (the technological) over another (the human). Well, at least, that is, over certain classes of humans. When it comes to technology that eliminates jobs, it’s appropriate to ask the question posed by R.G. Collingwood in his chapter on progress: “From whose point of view is it an improvement?”

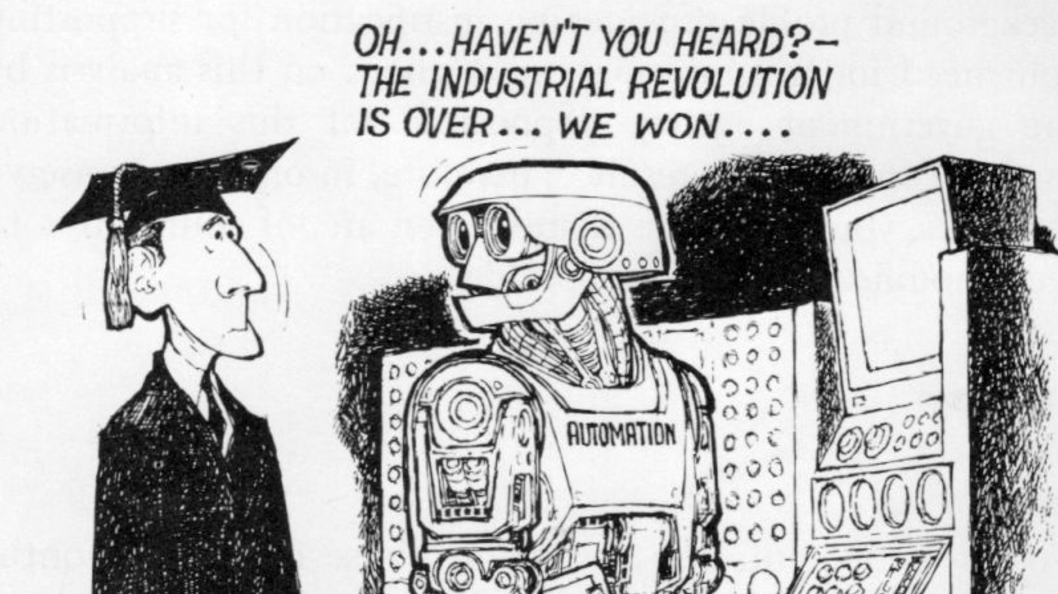

Many will immediately counter that elimination of jobs allows for “innovation” and the creation of new, previously unimagined forms of work. A 2015 study by economists at the consultancy Deloitte concluded that “the last 200 years demonstrates that when a machine replaces a human, the result, paradoxically, is faster growth and, in time, rising employment.” (See the graphic below)

But as Erik Sherman argues in Forbes, “that isn’t exactly [always] true”:

“During the industrial revolution, people didn’t simply find their former livelihoods disappear and then go on to the next phase of their lives, as we think of it. This is how the Gilded Age and terrible human oppression and widespread poverty on a massive scale happened.”

And then, as strange as it sounds to some, there’s a potential problem with the related goal of “efficiency”. The French philosopher Jacques Ellul warned that, in a “technological society,” where the overriding value of all actions is efficiency, man eventually becomes subordinate to the machine:

“Technical progress today is no longer conditioned by anything other than its own calculus of efficiency. The search is no longer personal, experimental, workmanlike; it is abstract, mathematical, and industrial. This does not mean that the individual no longer participates. On the contrary, progress is made only after innumerable individual experiments. But the individual participates only to the degree that he is subordinate to the search for efficiency, to the degree that he resists all the currents today considered secondary, such as aesthetics, ethics, fantasy. Insofar as the individual represents this abstract tendency, he is permitted to participate in technical creation, which is increasingly independent of him and increasingly linked to its own mathematical law.”

According to Ellul’s thinking, when technological innovations such as Amazon grocery stores are introduced, the member of the efficiency-driven society is expected to applaud and marvel without much consideration of its consequences, and with absolutely zero consideration of burying the technology (just writing that feels like heresy).

No matter how one feels about technology, that kind of unreflective response isn’t the mark of free individual or a free society. In fact, it’s just another form of automation.

—

Dear Readers,

Big Tech is suppressing our reach, refusing to let us advertise and squelching our ability to serve up a steady diet of truth and ideas. Help us fight back by becoming a member for just $5 a month and then join the discussion on Parler @CharlemagneInstitute!

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *