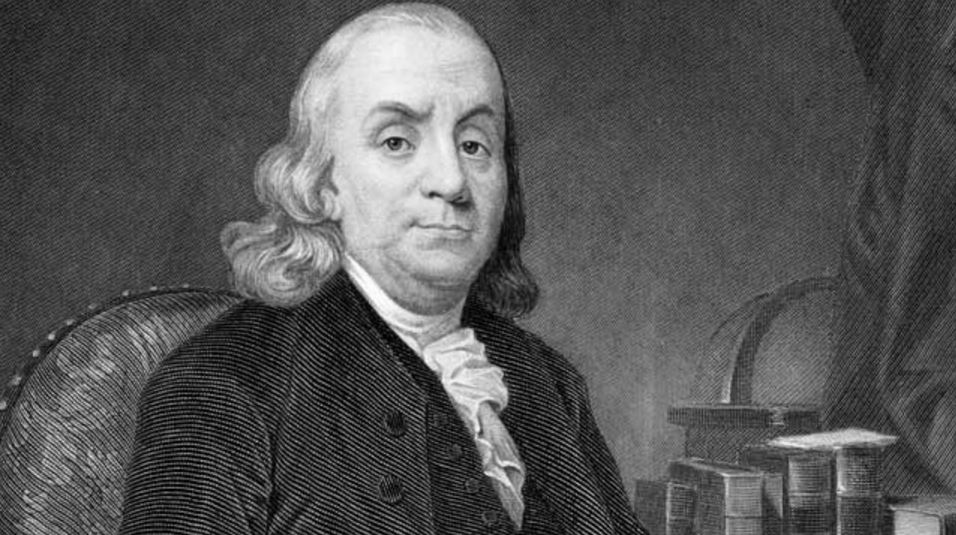

Contrary to the claims of some notable thinkers, among them the late Christopher Hitchens, Benjamin Franklin was not an atheist.

He was raised as a Presbyterian and discussed his faith at length in The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, the unfinished work Franklin wrote from 1771 to 1790. Here’s what he had to say on his faith:

I never was without some religious principles. I never doubted, for instance, the existence of the Deity; that he made the world, and governed it by his Providence; that the most acceptable service of God was the doing good to man; that our souls are immortal; and that all crime will be punished, and virtue rewarded, either here or hereafter.

Franklin was writing a record to be published posthumously, so there is no reason to doubt his truthfulness on this point. But Franklin’s autobiography also reveals a bit of personal distaste for religious services.

He notes what he regards as a “propriety” and “utility” of religious services, but he confesses that he “seldom attended public worship.”

The reason? At first blush, it might appear that an aversion to the local Presbyterian minister (the only one in Franklin’ hometown of Philadelphia, he claimed) was the cause.

[The minister] used to visit me sometimes as a friend, and admonish me to attend his administrations, and I was now and then prevailed on to do so, once for five Sundays successively. Had he been in my opinion a good preacher, perhaps I might have continued, notwithstanding the occasion I had for the Sunday’s leisure in my course of study; but his discourses were chiefly either polemic arguments, or explications of the peculiar doctrines of our sect, and were all to me very dry, uninteresting, and unedifying, since not a single moral principle was inculcated or enforced, their aim seeming to be rather to make us Presbyterians than good citizens.

This seems to be part of the answer. But it is the complete answer? A deeper look into the text suggests Franklin despised the ritual of religion.

Franklin was a man who took morality and self-improvement rather seriously. And it appears an over-emphasis of what he regarded as empty religious legalism put him off church.

At length [the minister] took for his text that verse of the fourth chapter of Philippians, “Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, honest, just, pure, lovely, or of good report, if there be any virtue, or any praise, think on these things.” And I imagined, in a sermon on such a text, we could not miss of having some morality. But he confined himself to five points only, as meant by the apostle, viz.: 1. Keeping holy the Sabbath day. 2. Being diligent in reading the Holy Scriptures. 3. Attending duly the public worship. 4. Partaking of the sacrament. 5. Paying a due respect to God’s ministers. These might be all good things; but, as they were not the kind of good things that I expected from the text, I despaired of ever meeting with them from any other, was disgusted, and attended his preaching no more.

One could see how a man as intelligent as Franklin might find such religious teaching dry and (perhaps more importantly to Franklin) non-utilitarian.

Have modern religious services generally improved in this regard? Or do services often still fail to provide religious teaching that is intellectually stimulating and utilitarian?

—

3 Comments

Tina

June 14, 2022, 11:50 pmReligion has failed to produce good, decent human beings for centuries. The US was founded to escape the bloody religious rule of Europe.

REPLYDaniel

June 14, 2024, 9:22 amFranklin is speaking for an Enlightenment critique of religion we find in Kant. The idea is that it should focus exclusively on morality, and not on religious doctrine and ritual. The problem is that religious doctrine provides the necessary metaphysical backdrop for morality, and ritual provides the habits necessary to build morality.

REPLYPeggy Behnke@Daniel

June 17, 2024, 11:05 amI left my Catholic Church at 14 because it was ritual, duty, not love….I loved attending protestant church services where the word was taught, and songs of praise were sang.

REPLY