Oberlin College in Ohio is ranked as one of America’s most liberal colleges, and has become something of a microcosm of the PC culture that pervades college campuses today. Last year they were in the news for publishing an official document advising faculty to avoid presenting potential “triggering material.” Most recently, we highlighted an article in The Atlantic that discussed Oberlin’s Microaggressions site, which provides a forum “for students who have been marginalized” at the school.

Oberlin’s progressivism has some provenance, though in the past it was a progressivism that both liberals and conservatives today would applaud. As reported on their website, they were “the first institution of higher education in America to adopt a policy to admit African American students (1835) and the first college to award bachelor’s degrees to women (1841) in a coeducational program.”

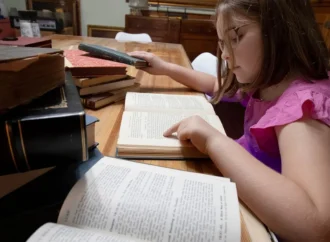

But it looks like Oberlin may have been a bit less progressive when it came to its past curriculum standards. 100 years ago, Oberlin required entering students to have read at least 15 of the following classic works:

Chaucer: The Prologue

Shakespeare: The Merchant of Venice, Macbeth, As You Like It, Henry V, Julius Caesar, Twelfth Night

Spenser: The Faerie Queene, Book I

Milton: Comus, Lycidas, L’Allegro, II Penseroso (the last three to count as one item)

Bunyan: The Pilgrim’s Progress, Part I

Addison and Steele: The Sir Roger de Coverley Papers

Pope: The Rape of the Lock

Goldsmith: The Vicar of Wakefield, The Deserted Village

Irving: Life of Goldsmith, Sketch Book

Coleridge: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Scott: Ivanhoe, The Lady of the Lake, Quentin Durward

Franklin: Autobiography

Palgrave: Golden Treasury, First Series, Parts II and III, Part IV

Lamb: Essays of Elia

De Quincey: Joan of Arc, The English Mail Coach

Hawthorne: The House of the Seven Gables

Thackeray: Henry Esmond

Carlyle: Heroes and Hero Worship, Essay on Burns

Macaulay: Essay on Addison, Life of Johnson, Lays of Ancient Rome

Burke: Speech on Conciliation with America

Washington: Farewell Address

Webster: First Bunker Hill Oration

Mrs. Gaskell: Cranford

Dickens: A Tale of Two Cities

George Eliot: Silas Marner

Blackmore: Lorna Doone

Ruskin: Sesame and Lilies

Byron: Mazeppa, The Prisoner of Chillon

Lowell: The Vision of Sir Launfal

Arnold: Sohrab and Rustum

Longfellow: The Courtship of Miles Standish

Tennyson: Gareth and Lynette, Lancelot and Elaine, the Passing of Arthur

Browning: Ten selected lyric or narrative poems

I also thought it interesting to read this statement from Oberlin’s 1915 catalogue:

“From the beginning of its history Oberlin has been an avowedly Christian College, and has steadily aimed to build on the deepest and most solid convictions of the best Christian people. It has sought to furnish an atmosphere in which parents desiring the completest education and the highest development in character would gladly place their children. Its fundamental convictions have been that all truth is one and to be fearlessly welcomed; that character is supreme; that Christ is the world’s one perfect character and completest revelation of God; and that the church is the one great world organization for ideal ends. It has intended to lay a practical daily emphasis on the ethical and spiritual in education—on life and faith, and at the same time allow the fullest freedom of thinking within the broadest Christian lines. The College has never had a creed or any denominational control; but it has believed in a loyalty to Christian truth that should manifest itself in a persistent and earnest application of that truth to the life of the world.”

Today, this is the kind of literary prerequisite list and statement of faith one would expect to see at a conservative college such as Hillsdale or Grove City. Interesting how things have changed…

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *