It has become fashionable in academia and pop culture to claim that historical figures previously assumed to be heterosexual were actually homosexual. The trend has taken root to such a degree that the cases crop up with a dull predictability, and great authors seem particularly vulnerable to having their sexual identities rewritten by modern scholars.

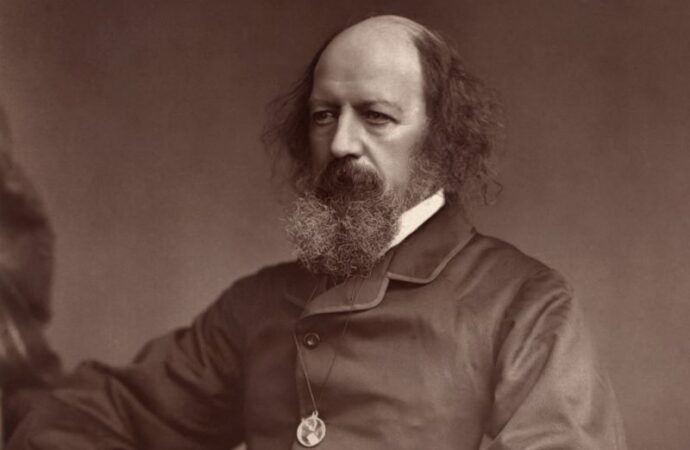

Due to the open-endedness inherent in many strains of literary interpretation, scholars and critics are able to imbue a wide range of passages with queer and erotic undertones through “queer theory” interpretations. They go something like this: “The stormy imagery of this line, placed in close proximity to the description of the male friend’s elbow, reveals the wild physical desires tearing apart the poet as he seeks to sublimate them in compliance with the hegemonic heteronormativity of his time.” Shakespeare is a frequent target, along with Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Recently, I was writing a piece about the close friendship between Tennyson and one of his college comrades, Arthur Hallam, and, not surprisingly, I found that many people like to claim the friendship was really a homosexual relationship. For example, Tennyson was classified as an “LGBT historic figure” on a tour for schools on England’s Isle of Wight, even though there’s no evidence to back up the claim that Tennyson was gay. The tour organizers said in their defense that Tennyson’s true sexual identity has been “obscured by heteronormative narrative.” But, of course, saying “we don’t have any evidence for our claim because someone hid it” isn’t a very convincing argument.

So, do any of the proponents of this theory provide any real evidence? Not really.

British author Garrett Jones wrote an entire book trying to prove the existence of a homosexual relationship between the two young men and was able to conclude, hesitantly, that perhaps they had an actively homosexual relationship, or perhaps they settled “for more-or-less disembodied, spiritualized passion” (also known as close friendship). In his review of Jones’s book, George Landow observes of Jones:

Although he writes quite clearly, he wants so desperately to believe in the homosexuality of these two Victorians that he unconvincingly interprets all texts and events important in this relationship as if he has a secret key and never even mentions contrary explanations. He isn’t, in other words, convincing at all, and he argues largely by assertion rather than demonstration.

I think this pretty well typifies the approach generally taken to writers’ supposedly hidden sexualities. The facts are forced to fit the thesis.

The 2013 biography of Tennyson by Professor Emeritus John Batchelor, in the chapters dealing with Hallam, refutes the possibility of homosexuality between the two men:

Tennyson obviously had a very strong attachment to Hallam, but it was never recognized by either of them as sexual; the complete innocence with which In Memoriam celebrates his feeling for his friend makes that certain. He saw the friendship as heroic and ennobling.

In a separate article, Batchelor says that Tennyson feared homosexual misreadings of his poem “In Memoriam” and revised it to avoid them.

There is nothing in “In Memoriam” that would lead us to conclude there was a sexual relationship between the two friends. The lines usually taken as “proof texts” can be just as easily understood as the expression of affection and loss within a “romantic friendship,” using physical metaphors, as poetry always does, something readily understood in non-sexual terms at the time the poem was written.

The reality is that what Tennyson and Hallam shared was what we call a “romantic friendship,” a not uncommon relationship between males throughout history, but which was not, generally, sexual. Romantic friendships even included a degree of physical closeness that we don’t see in American society today, but physical closeness is not to be equated with sexual desire, and this was a given for most of history. Consider that, even today, in France, a kiss is considered a normal greeting.

Those arguing that Tennyson and Hallam were homosexual would need something a lot sturdier than a few ambiguous lines of poetry to prove their case, given that Hallam was engaged to Tennyson’s sister, Emily (of whom he said, “I love her madly”), before his untimely death, and Tennyson went on to get married and have children.

So, in light of the lack of hard evidence that Tennyson was homosexual, what’s the motive here? Why do scholars seek to “queer” Tennyson and so many other writers? There are, of course, authors who really were homosexual, pretty well beyond a doubt, such as Oscar Wilde. Why, then, try to shoehorn other, clearly heterosexual, literary figures into the LGBTQ camp?

I would propose that this revision of history is used to promote the narrative that homosexuality is common and that the most admired figures in history were sexual deviants. LGBTQ advocates project their political goals onto the past, enhancing the image of the group. Professor Frank Fuerdi explains:

There is a way in which historical figures are seen as reflections of our contemporary society and its social groups. So Joan of Arc becomes trans, and all these historical figures are now ascribed the label of LGBTQ. There is this impulse to read history backwards. This is just a kind of anachronistic projection.

In addition, this phenomenon is partly the result of the modern equation of any profound or passionate feeling with sexual desire. The modern sex obsession tears out the soul and the heart and reduces human beings to their sexual organs and appetites. The modern mind often cannot fathom the possibility of desires, affections, or emotions about another person that don’t come down to a wish for physical gratification.

In the case of men in particular, we no longer understand a language of love, devotion, loyalty, and tenderness apart from homosexuality, even though, for most of history, men have had non-sexual relationships with one another that were nevertheless quite deep and devoted.

Our concept of love—particularly between men—has been so watered down, so degraded, that we cannot separate it from mere physical passion. We do not distinguish between types of love, as the Greeks used to. Due in part to our rampant materialism, we pollute the word love to the point that it means only the expression of the pleasure something gives us (as in “I love ice cream”), and in the context of human relationships, we are generally thinking of the pleasure of sexual intercourse, often in an entirely selfish sense. The notion of sacrificial love, of concern for the other, of charity, has been all but lost.

This is why we misunderstand the poetry of Tennyson—much to our loss. We could learn some things from Tennyson and Hallam about building deep friendships based on shared love of ideas and art, political commitments, and, most importantly, a commitment to the good of the other.

Overlaying sexual identities onto historical celebrities to promote the LGBTQ cause not only promotes historical errors, but, in addition to that, it’s damaging to friendships among straight males. The truth is that men need close, devoted friendships with other men, but many straight men don’t build that kind of relationship due to the associations with homosexuality. Most men have no concept of a deep “romantic friendship,” and if they did, they’d feel they had to steer clear of it since society would immediately jump to false conclusions. In many cases, men don’t know how to relate to one another on a deeper level, as they once did.

No wonder men are lonely. In some circles, anything other than talking about sports, video games, and women’s bodies is considered unmanly. It’s a tragic loss.

—

Image credit: Public domain

14 comments

14 Comments

John S.

February 23, 2024, 12:21 pmThis is so true. Just look no further than the Wikipedia entry for Alcuin of York, the Benedictine monk who advised Charlemagne on his efforts to restore culture in Christendom. Based upon a single baseless entry from a single book, this good monk's name is slandered. Simply pitiful.

REPLYJB

February 23, 2024, 12:46 pmWow! Nicely done.

REPLYJohn Chalus

February 23, 2024, 4:15 pmHomosexuals etc. need heroes so they make them up.

REPLYPeter

February 23, 2024, 8:44 pmAbout 12 years or more ago, I told my "open minded" high-school age daughter than the relentless "normalisation" of homosexuality would destroy friendship for men. How sad to see my words coming true so soon!

REPLYJay

February 23, 2024, 9:58 pmWhile I tend to agree with your premise that currently there’s a great deal of overreach in the attempt to identify “queer” individuals in history, your article has one rather glaring omission about why there’s so little evidence available to support those attempts. The sodomy laws at the time could have resulted in the imprisonment, torture, and death of the men involved in homosexual activity, which made it exceedingly unlikely that any participants would write about or leave other evidence of their attractions or activities. While there were many non-sexual “romantic” relationships between men in history, there’s also no doubt that some relationships between men were in fact sexual. Those relationships were, of course, hidden because of fear of retribution under the laws.

Further, it’s become known that Church fathers and historians regularly excised information from ancient texts about such sexual relationships due to Church opposition to the behavior. That information has only become commonly available in the last 30 or 40 years.

Your acknowledgment of those facts and the resultant lack of available evidence, as well as your exploration of how this lack of information is related to the current overreach would improve your article.

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/victims-of-a-cruel-prejudice-the-last-two-men-to-be-executed-for-sodomy-in-england/

REPLYWalker@Jay

February 24, 2024, 9:07 amThis is an interesting and fair point. Thanks for the feedback.

REPLY