Frivolity is killing America.

That’s an overstatement, but it’s not too far from the truth. While the neglect of morals, absolute truth, and traditional sex roles is clear from even a cursory glance at society, the slow degradation of the mind often hides in the background. Frivolity is worth considering, if only because it’s so often forgotten.

Prophecies of Doom

Aldous Huxley, philosopher and author of Brave New World, seemed to believe that frivolity would be the world’s doom. Contrary to George Orwell, writer of Animal Farm and 1984, Huxley “prophesied” (via implication) that the world would not necessarily be ruined by external government oppression. Instead, our internal love of the futile would destroy us.

This “prophecy” is embodied in Huxley’s 1932 fiction work Brave New World and in Ray Bradbury’s 1953 dystopic Fahrenheit 451. Both of these books portray a world overrun with entertainment: a world immersed in futile loves and an inability to appreciate substance. In both books, the centrality of entertainment and immediate gratification degrades its societies’ consciousness, causing culture to scorn deep, sustained thought.

“In Huxley’s vision, no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity and history,” says cultural analyst and author Neil Postman in his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. “As he [Huxley] saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.” While Orwell prophesied a society overrun by what we hate (governmental overreach, for instance, or control via the infliction of pain), Huxley feared we’d be destroyed by what we love. Entertainment would be our downfall.

Amusing Ourselves to Death

Postman believed that Huxley was right, and he warns the American people against the dangers of excessive entertainment. Postman summarizes his book like this:

“[Amusing Ourselves to Death] is an inquiry into and a lamentation about the most significant American cultural fact of the second half of the twentieth century: the decline of the Age of Typography and the ascendancy of the Age of Television. This change-over has dramatically and irreversibly shifted the content and meaning of public discourse, since two media so vastly different cannot accommodate the same ideas.”

In other words, when the primary form of communication shifts to television, images, and entertainment, we cannot retain the same kind of culture. Television does not communicate in the same way as books do: While books require sustained thought, television requires only momentary attention. While propositions require context and prior knowledge, TV shows and visual entertainment are often designed to stand alone. And while text is capable of directly expressing moral obligations or future possibilities, demonstrating what ought to be, images focus on our current attention, displaying only one instant.

What’s Happening in 2023

Television and images are prolific in 21st century America. The statistics are almost depressing: On average, people in the United States spend about three hours a day watching TV. Over a year, this habit results in over 45 days spent staring at a television. And these statistics do not include time spent scrolling through social media where addictive apps like TikTok and Instagram drain our attention.

This extreme immersion in entertainment most certainly affects the contemporary consciousness. How can television, with its insistence on entertainment and constant stimulation, teach us to faithfully embrace the unpleasant or stale? How can 20-minute immersions in a carefully tended reality teach us to analyze and evaluate the real world? How can the oscillating interests of contemporary consumers provide for the focus and determination that are essential to a well-lived life?

It’s not that television is all faulty, or that we ought to completely reject entertainment. There’s nothing wrong with watching an occasional good show; there’s nothing inherently faulty about video games or televised entertainment. However, a life centered on these things quickly becomes abhorrent, wasteful, and deadly. “We all build castles in the air,” Postman says. “The problems come when we try to live in them.”

Frivolity Withheld

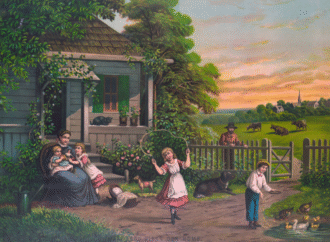

Fortunately for contemporary America, we are not required to dwell in castles of constant entertainment. While the present culture makes it more difficult than ever to avoid frivolity, living well is possible. We can take practical steps (like reading books, learning useful skills, or planning focused family time) to begin thinking deliberately about our experiences. As we rightly think about our purpose and life goals, we can avoid fulfilling Huxley’s prophecy. We can avoid amusing ourselves to death.

—

Image credit: Flickr-Jenny Downing, CC BY 2.0

2 comments

2 Comments

Richard

February 5, 2023, 12:43 pmLet us not forget memes which conservatives do instead of something.

REPLYTheophilus Ghoststone

February 5, 2024, 6:11 pmIt's curious that you left out Americans' obsession with sports.

REPLYThe ultimate frivolity.