Necessity is the mother of invention.

So is desperation.

It was nine o’clock in the morning, and I had volunteered to entertain five grandchildren, ages eight and under, for two hours so that a daughter-in-law might complete some paperwork. As I trudged up the stairs, coffee mug in hand, I wondered what I could do with children for whom the word “active” falls woefully short in application. It was raining outside, so the back deck wasn’t an option. Given their disparate ages and their whirl-a-gig energy, reading books together was out of the question. Legos might work for the older three, but with the younger two, the four-year-old and two-year-old, I would spend the time playing policeman, trying to keep them from destroying their older siblings’ forts and houses.

When I came into the living room, the gang had spilled out a large bin of “dress-up clothes.” The eight-year-old was a soldier, the five-year-old twins, a girl and a boy, were Owlet from PJ Masks and Batman, the four-year-old was Spiderman, and the two-year-old in her pajamas was a conundrum.

At that moment, inspiration struck.

“I’m going to tell a story,” I said to this band of variegated heroes, “and you’re going to act it out.”

Summoning up my meager gifts of showmanship, I lined them up and explained that I would tell a story and whatever I said, they must do.

And so we commenced our adventure. Sergeant Rock – I dragged the name up from a comic book hero of long ago – had a belt whose large golden buckle contained a secret code we needed to deliver to the “good guys.” The “bad guys,” led by an evil monster of a man named Grooge – a fusion of Grinch and Scrooge – was hot on the trail of this intrepid band. They ran, they waded across streams, they crawled beneath jungle vines, but all to no avail. Grooge and his evil followers finally chased them down.

Though the two-year-old toddled in and out of my narrative, the other four at this point followed my directions, dashing up a hill and piling up boulders (blankets) to make a defensive wall. In the ensuing battle, these defenders of the good and the noble laid low many of Grooge’s men, but slowly the sheer numbers of the enemy took their toll. Just as it seemed our embattled quintet might be overrun, the U.S. Army Rangers, whom Sergeant Rock had summoned earlier by walkie-talkie, came to the rescue and drove off the last of Grooge’s men.

“Why did you let the Grooge and some of the bad guys get away?” the eight-year-old asked me when the drama ended.

“Why, so we could have another story later on,” I said, an answer that brought a wide grin.

Because of frequent pauses to explain certain words – “What’s a code?” – and helping the younger ones learn such tasks as climbing imaginary trees, forty-five minutes had elapsed. The kids then ate a snack, followed by an hour of drawing pencils, crayons, and paper.

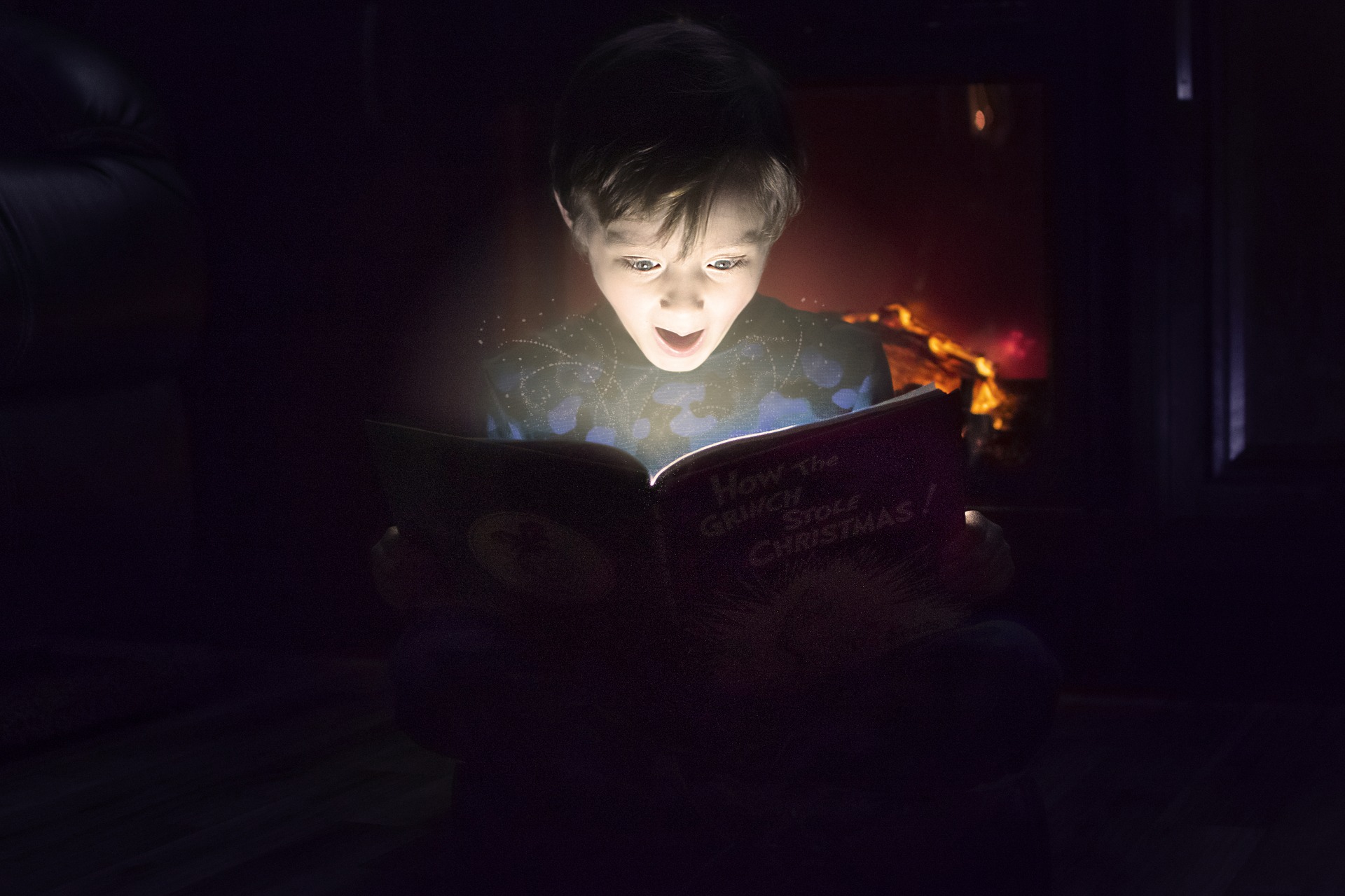

I describe this event because that morning drove home in me the power of storytelling. The grandkids, even the two-year-old who couldn’t possibly comprehend the plot but savored the action, were wholly engaged in trying to defeat Grooge.

Storytelling is surely among the most ancient of the arts. Thousands of years ago, human beings huddled around their fires and shared tales of a hunt or a battle, or of the gods. Today we still love stories, listening to audio books in our car, laughing as our favorite comedians embellish some mishap, taking strength and courage from “the good guys” in novels, biography, and books of faith. Open any of the bestselling volumes of the Chicken Soup For The Soul series, and what do we find?

Stories.

Some, of course, are better storytellers than others. These are the people practiced in the art of elaboration who can spin a yarn with enthusiasm and recreate some incident with such vivid gestures and language that we can see it in our mind’s eye. An acquaintance of mine made his living in part telling stories of Appalachia. My Uncle John, now long deceased, used to entertain me on summer evenings with tales of his boyhood and the Civil War veterans he’d known.

Of course, telling stories won’t build a computer or a car, lower mortgage rates, or reduce the federal debt in Washington. The world rolls along on rails made from facts, statistics, and data. In the opening lines of Dickens’ Hard Times, Mr. Gradgrind announces, “Now, what I want is Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts; nothing else will ever be of any service to them.”

Facts, data, statistics, reason: all are necessary to keep those wheels rolling.

But as Mr. Gradgrind learns, it is the passions that power the engine of that vehicle. Love and hate, triumph and failure, hope and despair, laughter and tears: these elements make us fully human, and these are what we so often convey in our stories.

After all, what are we if not stories ourselves, each and every one of us living protagonists in a magical and mysterious narrative we can scarcely apprehend?

—

Image Credit:

Pixabay

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *