In recent years, people have protested the racism of Confederate statues, Hollywood and sports mascots.

But a curious campaign has taken place on Indiana University’s Bloomington campus. Students have circulated petitions and organized protests seeking the removal or destruction of painter Thomas Hart Benton’s 1933 mural “A Social History of Indiana,” which contains an image of the Ku Klux Klan.

“It is past time that Indiana University take a stand and denounce hate and intolerance in Indiana and on IU’s campus,” a petition from August read.

A detail from the controversial panel of Benton’s mural. Bart Everson, CC BY

In September, the university announced that it would stop holding classes in the room where Benton’s painting is placed, and it would keep the room sealed off from the general public.

As the author of four books on Benton, I propose that the protesters take a closer look at Benton’s life and Indiana’s political history before they reflexively denounce the mural’s imagery.

A painter of the people

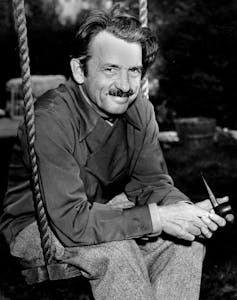

Along with Grant Wood (of “American Gothic” fame), Thomas Hart Benton (below right) was the leader of the Regionalist movement in American art, which proposed that sections of the country hitherto thought of as artistic wastelands, such as the South and the Midwest, could be suitable subjects for art.

Benton’s “America Today” (which can now be viewed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) was the first major American mural painting to focus on contemporary working-class Americans, rather than heroes in colonial garb or allegorical figures.

Throughout his life and career, the painter adamantly denounced racism. One of the very first articles he published, a 1924 essay in the journal “Arts,” contains a snide dismissal of the Klan. In 1935, he took part in a widely publicized exhibition, “An Art Commentary on Lynching,” organized by the NAACP and staged at the Arthur Newton Gallery in New York; and in 1940 he explicitly denounced racism of any sort, declaring:

“We in this country put no stock in racial genius. We do not believe that because a man comes from one strain rather than another, he starts with superior equipment.”

What’s more, to a degree very unusual at the time, Benton actively sought out and befriended African-Americans. He taught African-Americans in his art classes, used African-Americans as models for his paintings and invited African-Americans to dinner in his Kansas City home (a gesture that was still raising eyebrows in the city in the 1980s, when I worked as a curator there). He even learned to speak Gullah, the African-American dialect of the Sea Islands.

The Klan in Indiana

Benton’s murals take on added significance when we consider their historical context. (Art historians Kathleen Foster and Nanette Brewer tell the full story in their excellent catalogue on the murals.)

In the 1920s, the Klan dominated Indiana politics. Counting among its members the governor of Indiana and more than half of the state legislature, it had over 250,000 members – about one-third of all white men in the state. While devoted to denying equal rights to African-Americans, the group also denounced Jews, Catholics and immigrants.

Only the relentless coverage of the Indianapolis Times turned the tide of popular opinion. Because of the paper’s reporting, the state’s KKK leader, D.C. Stephenson, was convicted of rape and murder of a young schoolteacher.

Stephenson’s subsequent testimony from prison would bring down the mayor of Indianapolis, L. Ert Slack, and Governor Edward L. Jackson, both of whom had forged close political and personal relationships with the Klan. In 1928, the Indianapolis Times won a Pulitzer Prize for its investigative work.

Five years later, a handful of state leaders approached Benton to see if he would be able to paint a mural for the Indiana pavilion at the Chicago World’s Fair. The group included progressive architect Thomas Hibben and Richard Lieber, the head of the state’s park system. (Lieber appears on the right side of the controversial panel, planting a tree.)

They seem to have chosen Benton because of his progressive political views. But they were also drawn to Benton because no other American artist seemed capable of completing such a massive undertaking on such a short deadline.

The fair was less than six months away.

A refusal to whitewash history

Working at a frantic pace, Benton spent the ensuing months traveling around the state and making studies. Then, in a mere 62 days, he executed the entire project, which was over 12 feet high, 250 feet long and contained several hundred figures. It was the equivalent of producing a new, six-by-eight-foot painting every day for 62 straight days.

In 1941, the murals were installed in the auditorium at Indiana University Bloomington, where they remain today.

In the controversial panel, Benton painted a reporter, a photographer and a printer into the foreground – an homage to the press of Indiana for breaking the power of the Klan. In the center, a white nurse tends both black and white children in City Hospital (now Wishard Hospital).

The sinister figures of the Klan are visible in the background, behind the hospital beds – a reminder, perhaps, that racial progress can always slide backwards.

As Lauren Robel, the provost at the University of Indiana, recently wrote in a statement to the university community:

“Every society that has gone through divisive trauma of any kind has learned the bitter lesson of suppressing memories and discussion of its past; Benton’s murals are intended to provoke thought.”

Benton clearly felt that the state government’s support of the Klan was something that should not be whitewashed.

He applied the same approach a few years later in his murals in the Missouri State Capitol: They open with a scene of a fur trader selling whiskey to the Indians, and close with a scene of Kansas City’s notorious political boss, Tom Pendergast, sitting in a nightclub with two trustees of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Not everyone in Missouri was pleased.

Interestingly, representations of the Klan by other artists of the 1930s, such as Philip Guston and Joe Jones, continue to hang in museums. No one has proposed that they be taken off view. Something about the fact that Benton brought his paintings out of museums – and into public spaces not consecrated to “art” – seems to have given his work an in-your-face immediacy that still stirs up controversy.

I find it rather sad that the paintings have been taken off view; if it’s the only way to ensure the safety of the paintings, it’s the right decision. But hopefully it’s a temporary one.

![]() At the heart of the matter is the question of whether we should seek to try to forget the dark episodes of the past, or whether we should continue to confront them, discuss them and learn from them.

At the heart of the matter is the question of whether we should seek to try to forget the dark episodes of the past, or whether we should continue to confront them, discuss them and learn from them.

–

Henry Adams, Ruth Coulter Heede Professor of Art History, Case Western Reserve University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *